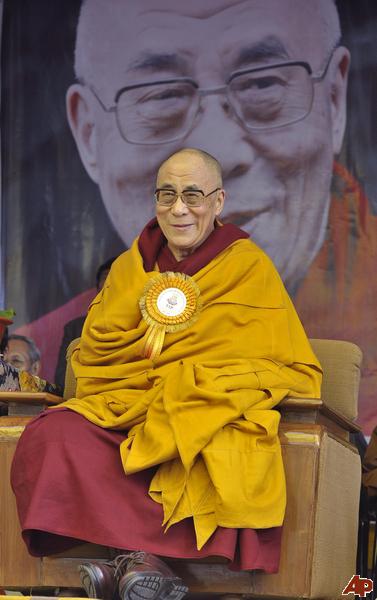

Teachings given at Los Angeles, CA 2000 by His Holiness the Dalai Lama on Illuminating the Path to Enlightenment : Relying on a Spiritual Teacher

His Holiness the Dalai Lama

The qualities of a teacher

Lines of Experience: Verse 8

Although (there is much merit to be gained from) reciting or hearing even once this manner of text (written by Atisha) that includes the essential points of all scriptural pronouncements, you are certain to amass even greater waves of beneficial collections from actually teaching and studying the sacred Dharma (contained therein). Therefore, you should consider the points (for doing this properly).

Lama Tsong Khapa’s Lines of Experience is a key to the connections and relationships between all the various scriptural texts. Verse 8 presents how the teacher should teach and how the students should listen, so that both teaching and listening are successful and effective.

It is very important that the teacher has the right motivation and attitude. If the teacher is motivated by mundane aspirations, such as wanting to be known as a great scholar, to attract money or other material offerings or to bring people under his or her influence, then that teacher’s motivation is certainly polluted. It is very important that a teacher’s motivation for teaching be the pure, altruistic aspiration to be of service and benefit to others. According to traditional Tibetan teachings, not only should a teacher ensure purity of motivation but also the manner of giving the teaching should not be flawed. Teaching in a flawed way is likened to an old man eating; he chews only the soft food and puts the hard bits aside. Similarly, teachers should not just focus on the simple points and leave out the difficult ones. It is also said that teachers should not teach Dharma like crows build nests. When crows build nests, there is no systematic order; it’s totally chaotic. Similarly, Dharma teachers should not teach chaotically but should offer a correct, systematic presentation that will benefit their students.

Another quality that ideally a teacher should have is experiential knowledge of the topic being taught. If that is not possible, then the teacher should have some familiarity with the practice of that topic, in order to be able to draw on personal experience. If that is not possible either, then at least the teacher should have a thorough intellectual understanding of the topic. As Dharmakirti said, there’s no way that you can reveal to others that which is hidden to yourself.

I have a friend who is a great teacher and a very learned Hindu master. One day we were talking about the issue of inter-religious harmony and the need for greater communication among the different faiths. I remarked that I am completely ignorant on matters of Islam and don’t have much contact with the Islamic world. He replied, “Well, it’s not that difficult. Just learn to quote a few verses from the Koran and come up with some commentary here and there. That should be enough. You don’t really have to know more.”

A more serious example involves a German scholar who attended a discourse by a Tibetan teacher. During the discourse he heard things that contradicted some of the basic teachings of the Buddha, so after the lecture, he went up to the teacher in person and told him that it seemed he had made some mistakes. Instead of acknowledging these mistakes, the Tibetan teacher said, “Oh, it doesn’t matter. You can say stuff like that.” This is wrong; it’s very important for teachers to be careful.

When giving teachings from a throne, teachers’ physical conduct is also very important. Before sitting down, teachers should make three prostrations towards the throne. This is to remind them that teaching from a throne does not mean that they are being recognized as great or holy beings but rather reflects the respect that is being accorded to the Dharma being taught. According to the Mahayana tradition, when the Buddha gave the teachings on the perfection of wisdom, he himself made a throne to sit on in order to show respect for these sutras, which are considered to be the mother, or source, of all aryas, be they hearers, solitary realizers or fully enlightened buddhas.

When the Buddha’s sutras were compiled by the early arhats and later by other followers of the Buddha, there were times when all the members of the congregation would remove their outer yellow robes. The person supervising the compilation process would fold and stack them up to make a throne and then sit on this throne of robes and compile the sutras. All this shows the tremendous respect accorded the Dharma.

Once the lama has sat down on the throne, the Tibetan custom is for him to recite a sutra reflecting on impermanence, to keep his motivation pure and prevent pride or conceit from arising in his mind. Such practices are important in ensuring purity on the teacher’s part, because when you’re sitting on a high throne and people start praising you, there’s a real danger of pride and arrogance taking over.

Therefore, we should take to heart the instructions of the Tibetan master, Dromtönpa, who said, “Even if the whole world venerates you by placing you on the crown of their head, always sit as low as possible and maintain humility.” In the Precious Garland, Nagarjuna makes aspirational prayers to be like the elements of earth, water, fire and wind, which can be enjoyed and utilized by all sentient beings. If you take such sentiments seriously, you will never think that you are better than others or to try to bring them under your control.

It is also very important to have pure motivation when you receive teachings; to ensure that you have the three qualities of the ideal student— an objective mind, intelligence and a deep interest in the teachings— and that you cultivate the appropriate attitude. In this way, you will become a suitable recipient of the teachings. You should regard the Dharma as a mirror and the actions of your body, speech and mind as what that mirror reflects. Constantly examine what you see in the mirror of Dharma and continually try to modify your behavior.

One feature of the Buddha’s teaching is that the greater the diversity of your resources and avenues of contemplation, the more effective will be your understanding and experience, and the deeper the conviction you acquire. Therefore, you must ensure that your approach to your practice is comprehensive and that your learning and understanding are vast. At the same time, you must also ensure that the things you learn do not remain merely at the intellectual level. Right from the start, your studies should be directed towards the objective of practice. If you study without the desire to relate what you are learning to your own life through practice, you run the risk of becoming hardened or apathetic.

The great Kadampa masters used to say that if the gap between the Dharma and your mind is so big that a person can walk through it, your practice has not been successful. Make sure there’s not the slightest gap between the teachings and your mind. You need to integrate and unite the Dharma with your mind. A Tibetan expression says that you can soften leather by kneading it with butter, but if that leather is hard because it’s been used to store butter, you can never soften it, no matter how hard you try. Since you don’t store butter in skin containers in the West, perhaps that saying doesn’t make sense, but you get the idea.

The Kadampa masters also used to say that the water of Dharma can moisten the earnest, fresh minds of beginners, no matter how undisciplined they are, but can never penetrate the minds of those hardened by knowledge.

Therefore, learning and knowledge must never override your enthusiasm for practice, but neither should your dedication to practice interf e re with your commitment to study. Furthermore, both your knowledge and dedication to practice must be grounded in a warm, compassionate heart. These three qualities—scholarship, dedication to practice and compassion— should be combined.

If teachers and students prepare their minds as above, students can experience transformation, even while listening to teachings.

Finally, at the end of each session, both the student and teacher should dedicate their merit to the enlightenment of all sentient beings.

In the Tibetan tradition, there are two main ways in which a teaching session can be conducted. In one, the primary objective is to help students gain a clearer understanding of the various philosophical points of Dharma. In the other, the main emphasis is on specific aspects of the individual’s practice, where specific problems encountered in meditation are addressed.

Broadly speaking, when great treatises such as the five major works by Indian masters dealing with Middle Way philosophy are taught, the primary objective is to help students gain deeper understanding and clarity. However, when texts such as the lam-rim are taught, more emphasis is placed on the practical application of specific meditation practices, and instructions are given on a step-by-step basis.

There is also a unique style of teaching known as “experiential commentary,” where the teacher teaches one specific topic at a time. The student then practices this topic for a prolonged period of time, and only when the student has had some experience will the teacher take him or her to the next step. In this way, the teacher guides the student through an experiential understanding of the subject matter.

Dromtönpa summarized the ideal qualities of a Mahayana teacher—profound resources of knowledge in all aspects of the Dharma, being able to draw on both sutra and tantra and explain the relationship between various ideas from different philosophical perspectives; the ability to see what is most effective for an individual student at any particular time; and the ability to recognize the particular approach most suited to a given individual.

The practice of reliance

Lines of Experience: Verse 9

(Having taken refuge,) you should see that the root cause excellently propitious for as great a mass of good fortune as possible for this and future lives is proper devotion in thought and action to your sublime teacher who shows you the path (to enlightenment). Thus you should please your teacher by offering your practice of exactly what he or she says, which you would not forsake even at the cost of your life. I, the yogi, have practiced just that. You who also seek liberation, please cultivate yourself in the same way.

From Verse 9 onwards, the main topic is the actual manner in which students are guided through the stages of the path. This is broadly divided into two sections. One is how to rely on the spiritual teacher, who is the foundation of the path, and the other is, having done that, how to engage in the actual practice of the stages of the path.

With respect to the former, Verse 9 explains the practice of proper reliance on a spiritual teacher [Skt: kalyanamitra; Tib: ge-wai she-nyen]. Just as there can be negative friends and spiritual friends, there can be both negative teachers and spiritual teachers.

With respect to ordinary, worldly knowledge, although in the final analysis what we learn comes through our own study and maturity of understanding, still, at the beginning, we need someone to introduce us to the subject matter and guide us through it. Similarly, when it comes to spiritual transformation, although true experiences come through our own development of knowledge and practice, we again need an experienced teacher to show us the path.

Since the spiritual teacher is so crucial to our practice, Lama Tsong Khapa goes into great detail in his Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path, presenting the topic in three broad categories: the qualifications of the spiritual teacher, the qualities required by the student and the proper teacher-student relationship.

The qualities of the spiritual teacher

The qualifications of a suitable teacher can be found in texts from the vinaya all the way up to the Vajrayana. Since here we are discussing Mahayana teachings in general, we will consider the ten qualifications of the teacher as presented in Maitreya’s Ornament of the Mahayana Sutras:

1. A disciplined mind (referring to the quality of having mastered the higher training in ethical discipline).

2. A calmed mind (referring to the quality of having mastered the higher training in meditation and concentration).

3. A mind that is thoroughly calmed (referring to the quality of having mastered the higher training in wisdom, particularly the wisdom of no-self [Skt: anatman; Tib: dag-med]).

4. Knowledge exceeding that of the student in whatever subject is being taught.

5. Energy and enthusiasm for teaching the student.

6. Vast learning in order to have the resources from which to draw examples and citations.

7. Realization of emptiness—if possible, a genuine realization of emptiness, but at least a strong commitment to the practice of emptiness on the basis of deep admiration for the teachings on it.

8. Eloquence and skill in presenting the Dharma so that the teaching is effective.

9. Deep compassion and concern for the well-being of the student to whom the teaching is given (perhaps the most important quality of all).

10. The resilience to maintain enthusiasm for and commitment to the student, not becoming discouraged no matter how many times the teaching has to be repeated.

The first three qualities relate to the practice and experience of the Three Higher Trainings of morality, concentration and wisdom. The other important qualities are having the realization of emptiness as the ultimate nature of reality and compassion for the student. Those who assume the role of teacher must ensure that these qualities are present within themselves.

When discussing these ten qualities in his Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path, Lama Tsong Khapa makes a very important point. He says that if your own mind is not disciplined, there’s no way you can discipline the mind of another.19 Therefore, if you want to be a teacher, you must first seek to discipline your own mind. He goes on to say that the way prospective teachers should discipline their minds is through the practice of the Three Higher Trainings.

Furthermore, teachers should not be limited to teaching just one or two points of Dharma but should be able to present particular practices with complete knowledge of their place within the overall framework of the Buddha’s teachings.

Lama Tsong Khapa concludes this section of his Great Exposition by emphasizing that practitioners seeking a spiritual teacher should familiarize themselves with these ten qualities and then look for them in those in whom they would entrust their spiritual welfare. When choosing a spiritual teacher, from the start, examine the person you have in mind to see if he or she really possesses these qualities. If you do so, you’ll reduce the risk of encountering serious problems later on.

Otherwise, you may use the wrong criteria to judge a teacher’s suitability. This used to happen in Tibet. Tibetans have tremendous faith in the Dharma, but their level of knowledge was not always equal to their devotion. Instead of assessing spiritual teachers by their inner qualities, people would base their judgment on external manifestations, such as the number of horses in a lama’s entourage. If a lama was traveling in a large convoy, people would say, “Oh, he must be a very high lama!” People like that also tended to regard what the lama was wearing—a unique hat, brocade robes and so forth—as an indicator of his spiritual greatness.

It is said that when Atisha first came to Tibet, his translator, Nagtso Lotsawa, and the Ngari king, Jangchub Ö, sent letters inviting all the high Tibetan lamas to come and receive this great Indian master. A large procession of lamas came to meet Atisha, and as they rode up on horseback, they could be seen from quite a distance. They were all dressed in very impressive-looking costumes with elaborate headgear shaped into fantastic designs, such as crows’ heads. When Atisha saw them, he covered his head with his shawl in mock terror and exclaimed, “Oh my! The Tibetan ghosts are coming!” When the lamas dismounted, they removed their brocades and costumes until they were wearing just their monastic robes, and walked towards Atisha, who then became very pleased.

On this subject, we can also look at the life of Milarepa, who shines as one of the crown jewels among Tibetan meditators. One day, the lama, Naro Bönchung, who had heard of Milarepa’s great reputation, went to visit him. When he met Milarepa in person, however, he was taken completely by surprise, and later remarked to someone, “This Milarepa is so famous, but when you actually see him, he looks just like a beggar.”

This reminds me of the humility of another great lama, the Kadampa master, Dromtönpa. The story goes that once, when Dromtönpa was traveling from one place to another, he met a Tibetan monk who had been walking for some time. This monk was very tired and his boots had begun to hurt his feet, so he took them off and, since Dromtönpa looked like just a humble layman, asked him to carry his boots. Dromtönpa took the heavy boots on his back without question. Later, as they approached a monastery, the monk noticed that all the monks were lined up on both sides of the road, obviously waiting to receive somebody. He thought to himself, “They didn’t know I was coming, and anyway, this reception could not possibly be for me,” so he turned to Dromtönpa and said, “This welcome is obviously for someone important. Do you have any idea who it’s for?” Dromtönpa replied, “It could be for me.” The monk looked at him in astonishment and, realizing what he had done, ran off, leaving his boots behind.

There is also a much more recent example. Around the turn of the century, there was a great meditation master and teacher named Dza Patrul Rinpoche, who was truly a great bodhisattva and embodied the teachings of Shantideva’s text, A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life. Dza Patrul Rinpoche had many disciples but often led the life of a wandering practitioner. Whenever he settled in one area, he would begin to attract disciples and particularly patrons. After a while, he would find it all too much and go elsewhere to seek solitude.

One of those times, Dza Patrul Rinpoche sought shelter in the home of an old lady, and started doing household chores while pursuing his spiritual practice. One day, as he was outside emptying the lady’s chamber pot, some lamas stopped by the house. They told the old lady that they had heard their teacher might be residing somewhere in the region and asked if she had seen him. She asked what he looked like, and as they started to describe his general appearance, the kind of clothes he wore and so forth, she suddenly realized that the person who was outside emptying her pot was the great Dza Patrul Rinpoche. She was so embarrassed that, just like the monk in the previous story, she too ran off. I heard this story from the late Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen.

The point of all this is that a true Mahayana teacher should be someone who enjoys simplicity, yearns to be anonymous and, as Tibetans would say, hides in solitude like a wounded animal. The Tibetan tradition states that Mahayana teachers should have at least two basic qualities. First, from the depths of their heart, they should regard the future life as more important than this. Without this, nothing one does becomes Dharma. Second, teachers should regard the welfare of others as more important than their own. Without this, nothing one does becomes Mahayana.

The qualities of the student

In his Great Exposition, Lama Tsong Khapa goes on to discuss the three principal qualifications of an ideal student:

1. An objective and open mind.

2. The intelligence to judge between right and wrong, appropriate and inappropriate.

3. Enthusiasm for and interest in the subject.

Objectivity and openness are critical, regardless of what you want to study. Bias is an obstacle to knowledge. Objectivity ensures that you are engaging in the Dharma in the right way and with the right motivation. The sutras and Nagarjuna’s Precious Garland both emphasize this and describe four wrong ways of approaching and engaging in the Dharma:

1. Engaging in the Dharma out of attachment to a particular tradition or custom.

2. Engaging in the Dharma out of hatred or hostility.

3. Engaging in the Dharma to seek temporary relief from some actual or perceived threat.

4. Engaging in the Dharma out of ignorance.

With respect to the second point, sometimes people have so much aversion to something that they embrace whatever opposes it. For example, there are people in India who are motivated to engage in the Dharma in rebellion against their traditional caste status as untouchables. They embrace Buddhism because of negative feelings towards their traditionally inherited religion.

The second quality of the ideal student, intelligence, is also very important, since it is intelligence that allows you to discriminate between right and wrong and so forth.

When commenting on this quality and the various attitudes that practitioners must have towards their teacher, Lama Tsong Khapa writes that students should relate to their teachers as loyal and respectful children. This does not mean that you should give your leash to anybody who is willing to take it, but only to one who possesses the right qualifications. To substantiate this point, he cites a vinaya sutra that says that if a teacher says something that contradicts the Dharma, you should not follow that teaching. Another passage states that if a teacher says something contradictory to the overall framework of the Buddha’s path, the student must point this error out to the teacher.

This reminds me of a story. The Tibetan master and learned scholar, Geshe Sherab Gyatso, used to attend the discourses of one of his teachers, Muchog Rinpoche. Whenever Muchog Rinpoche made some effective point, Geshe Sherab would immediately praise it and say, “Yes, these are powerful instructions. Deeply inspiring.” However, if Muchog Rinpoche said something contradictory to the teachings of the Buddha, Geshe Sherab would immediately rebuff what his teacher had said, saying, “No, no, no. Nobody should say such things.”

With respect to the third quality of the student, enthusiasm for and interest in the teachings, right at the beginning of the Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path, when Lama Tsong Khapa states his intention for writing the text, we find a request for the attention of readers who have the quality of objectivity, are endowed with the faculty of intelligence and wish to make their human existence meaningful. In order to make your life meaningful, you need enthusiasm for and interest in practicing the teachings, otherwise, whatever you learn is like the drawing of a lamp—it doesn’t illuminate anything—and your knowledge remains at the level of mere information.

We find similar exhortations among the Indian masters. In the salutation verses of his commentary on Maitreya’s Ornament of Clear Realization, Haribhadra states that his teacher, Vimuktisena, wrote a commentary on the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras. Vasubandhu, Vimuktisena’s own teacher, had also written a commentary on these sutras, but interpreted their ultimate meaning according to Cittamatra philosophy. Recognizing that his teacher, Vasubandhu, hadn’t fully understood the meaning of these sutras, Vimuktisena wrote his own commentary as a corrective. This shows that even students with great devotion and respect for their teacher should have the intelligence to point out any mistakes their teacher makes.

Another example concerns the Indian master, Dharmakirti, whose teacher was a student of the seventh century pandit, Dignaga. Dharmakirti used Dignaga’s text in his study of epistemology. As he read over the text with his teacher, Dharmakirti realized that even his own teacher hadn’t fully understood Dignaga’s meaning. When Dharmakirti mentioned this to his teacher, he invited him to write a commentary that would take his own interpretation as an object of critique.

All these examples show clearly that the great masters truly took to heart the Buddha’s own advice that his followers should not accept his words simply out of reverence but should scrutinize them in the way a goldsmith examines gold by rubbing, cutting and scorching and accept the validity of his teachings only on the basis of their own analysis.20

The Mahayana has a long tradition of subjecting the Buddha’s words to detailed analysis and examination, following that with an interpretative approach to discriminate between teachings that can be taken at face value and those that require further interpretation.21 This is necessary because there are certain scriptural teachings that, if taken literally, actually contradict reasoning and experience. These interpretations have been made by Mahayana practitioners and masters who have unwavering, single-pointed faith in the Buddha, some of whom have actually been willing to give up their lives in the service of the Dharma. Even such devoted masters subject the word of the Buddha to critical analysis.

Establishing proper reliance

In his Great Treatise, Lama Tsong Khapa goes on to describe the actual manner in which proper reliance on a spiritual teacher should be developed and established. “Reliance on a spiritual teacher,” he writes, “is the foundation of the path, because the spiritual teacher is the source of all temporary and (particularly) ultimate gain.” The point here is that if we encounter a genuine spiritual teacher, this person may be able to help us open our eye of awareness and lead us on the path.

The actual practice of relying on a spiritual teacher is performed through both thought and action, but relying through thought is the key. This entails the cultivation of two principal qualities, faith and respect. In the lam-rim, we often find citations from Vajrayana texts stating that we should perceive our teacher as a truly enlightened being. It is important to understand the significance of this practice.

By encouraging you to cultivate a perception of your teacher as an enlightened being, the lam-rim texts do not mean that such reliance on a spiritual teacher is indispensable. If you look at the structure of the lam-rim teachings, although all the practices are organized within the framework of the three scopes, those of the initial and middling scopes are regarded as common practices, the term “common” implying that they are not full or complete practices in and of themselves.

The initial scope teachings discuss the need to cultivate the yearning for a better rebirth and contain practices related to that aspiration. The middling scope teachings deal with the practices of the Three Higher Trainings of morality, meditation and wisdom, but even here they are not presented in full because they are still in the context of the Mahayana path. The point is that lam-rim texts are written assuming that the ultimate aim of the practitioner is to enter the Vajrayana path in order to reach enlightenment (the great scope). Therefore, even though the lam-rim teachings present the idea of perceiving your teacher as a truly enlightened being, it does not mean that every single spiritual practice depends upon that kind of reliance. Cultivating the perception of your teacher as a fully enlightened being is relevant only in the context of Vajrayana but not in the common practices.

The actual reliance on a spiritual teacher is done through the cultivation of certain thoughts, particularly faith, admiration and respect, based on the recognition of your teacher’s great kindness. It does not end there, however. In fact, the very purpose of cultivating such attitudes is to arouse enthusiasm for and dedication to your practice. By cultivating such thoughts as admiration and respect, you develop a deeper appreciation of what your spiritual teacher embodies, and your commitment and dedication to practice naturally increase. The best way of making an offering to your teacher is to practice what you have been taught. As Milarepa wrote, “I do not have any material things to offer my teacher, but still I have the best offering—my practice and experiences.”

Among the writings of the great masters we find a verse stating that while there might be a question as to whether single-pointed meditation can lead you to liberation, there is no doubt that deep faith in, devotion to and respect for your teacher will. This suggests that if, in the context of Vajrayana, you have deeply felt, single-pointed faith in and respect for your spiritual teacher, you will experience enormous enthusiasm and make great strides in your practice.

The Indian Chakrasamvara master, Gandapa [Tib: Drilbupa], wrote that your spiritual teacher alone can lead you to liberation. However, commenting on this point, Lama Tsong Khapa said that the term “alone” here is not exclusive but rather an emphasis placed upon the importance of relying on your spiritual teacher in the context of Vajrayana. Devotion to your teacher does not exclude the necessity of all the other practices, because devotion alone cannot lead to liberation. You need to understand the different contexts in which certain perspectives are relevant. If you have a broad understanding of the whole idea of reliance on a guru, it will help you deal with some of the problems and crises we see today in relation to this practice.

Question and answer period

Question. If I did not misunderstand what you said before, part of the practice of guru devotion is to point out where you think your teacher has gone wrong. First, what do you do when it is nearly impossible to express a dissenting opinion to your teacher because those around him or her tend to block the expression of criticism? Second, how do you reconcile holding fundamentally different views on certain issues from those expressed by your guru?

His Holiness. If a lama or spiritual teacher has done something wrong that needs to be pointed out, there could be two kinds of motivation for those immediately around the teacher—such as attendants or close disciples— trying to hide it or prevent people from disclosing it or pointing it out to the teacher. On the one hand, their motivation could be quite innocent; they might just be trying to protect and help their teacher. Such motivation is more the result of ignorance rather than willful manipulation of the situation. However, even if that’s the case, there is still the danger of causing harm to the teacher. In fact, a Tibetan expression says that extremely devout students can turn a true teacher into a false one.

On the other hand, the motivation of the attendants and close disciples could be more mundane—they may not want to make their teacher’s wrongdoing public for fear of harming his or her reputation. This is completely wrong, and you must find a way of expressing your concerns to your teacher. However, it is also very important to ensure that your own motivation is pure. You should not act out of hostility towards your teacher or out of the desire simply to express your displeasure. As the Mahayana teachings state, we must ensure that everything our teacher teaches accords with the principal teachings of the Buddha. We must also practice the motto of relying on the teaching and not the person.22

In response to your second question, it’s unlikely that you will have disagreements with your teacher on every single issue. That’s almost impossible. Basically, you should embrace and practice the teachings that accord with the fundamental teachings of the Buddha and disregard those that do not.

Question. Do we need a guru to get enlightened or is it sufficient just to study Dharma, live a moral life, attend teachings and practice meditation?

His Holiness. Of course it is possible to practice, study and lead a moral life without actually seeking a guru. However, you must understand that when you talk about enlightenment, you are not talking about something that can be attained within the next few years but about a spiritual aspiration that may, in some cases, take many lifetimes and eons. If you do not find a qualified teacher to whom you can entrust your spiritual well-being then, of course, it is more effective to entrust yourself to the actual Dharma teachings and practice on that basis.

I can tell you a story related to this. Dromtönpa was a great spiritual master who truly embodied the altruistic teachings of exchanging self and others. In fact, in the latter part of his life, he dedicated himself to serving people who suffered from leprosy. He lived with them and eventually lost his own life to this disease, which damaged his chin in particular.

As Dromtönpa lay dying, his head rested on the lap of one of his chief disciples, Potowa, and he noticed that Potowa was crying. Then Potowa said, “After you pass away, in whom can we entrust our spiritual well-being? Who can we take as our teacher?” Dromtönpa replied, “Don’t worry. You’ll still have a teacher after I’m gone—the tripitaka, the threefold collection of the teachings of the Buddha. Entrust yourself to the tripitaka; take the tripitaka as your teacher.”

However, as we progress along the spiritual path, at some point we will definitely meet an appropriate and suitable teacher.

Question. Many texts describe the practitioner’s goal as that of buddhahood itself, yet among seasoned Western Dharma teachers there seems to be a trend tow a rds accepting partial results, as if buddhahood is unattainable. This new attitude is that of accepting samsaric mind punctuated by spiritual phases and seems to be based on those diligent teachers’ inability to achieve complete liberation themselves. Is seeking buddhahood in this very lifetime still a viable goal in what the Buddha declared would be a dark age for Buddhism?

His Holiness. If you understand the process of attaining buddhahood from the general Mahayana perspective, the attainment of buddhahood within the period of three countless eons is actually said to be the quick version. Some texts speak about forty countless eons! However, according to the general Vajrayana teachings, practitioners with high levels of realization can prolong their lifespan and attain Buddhahood within a single lifetime. The Highest Yoga Tantra teachings recognize that even within this short human lifetime, the possibility of full enlightenment exists.

There is also the idea of someone being able to attain full enlightenment after a three-year retreat, which is not too dissimilar from Chinese communist propaganda. I make this comment partly as a joke, but partly in all seriousness—the shorter the time period of your expectation, the greater the danger of losing courage and enthusiasm. Leaving aside the question of whether it takes three or forty countless eons to reach enlightenment, when you cultivate deeply such powerful sentiments as those articulated in Shantideva’s prayer,

For as long as space exists,

For as long as sentient beings remain,

Until then, may I too remain

And dispel the miseries of the world,

time is totally irrelevant; you are thinking in terms of infinity. Also, when you read in the Mahayana scriptures passages pertaining to the bodhisattva’s practice of what is called armor-like patience, again time has no significance. These are tremendously inspiring and courageous sentiments. Font http://www.lamayeshe.com/index.php?sect=article&id=398