His Holiness the Dalai Lama: Stealing is another unskillful deed because it harms the possessions of others, so it also causes them suffering and should be avoided.

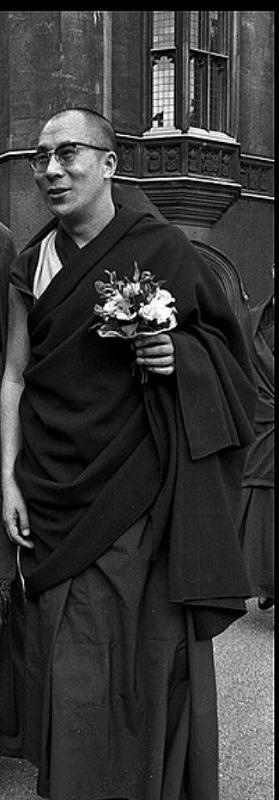

4 – The Thirty-Seven Practices of the Bodhisattvaby His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Bodhgaya 1974.

If one day goes, it’s a pity. If a month or a year is wasted, it’s much worse. Therefore checking up on oneself is important. If life would wait for us there would be no problem, but in fact it always races, and never lets us finish. If we make a good use of life, this is a great thing, otherwise it is wasted and runs away from us. “The three worlds are impermanent like an autumn cloud.” This being so, I do not need to repeat how beneficial and necessary Dharma practice is. Since we see it is worthwhile and necessary, if we spend time saying, “I will, I must practice Dharma”, and never put this into effect, then as Guru Rinpoche says, “Before the tomorrow of Dharma practice, the today of death may occur. Without deceiving yourself, therefore, to practice Dharma, start now.” Let us take my own case. If I say I have many things to do, so I’ll get around to it when I reach fifty, this is cheating myself.

So I must try, myself, not to postpone matters even for a second. If I do so it is my own fault, my weakness and my inability. Of course I cannot put 84,000 teachings into practice at once. Even someone like Nagarjuna did not practice the whole Dharma in one day. He started like ourselves, generated a will to practice and then advanced further, increasing his power and ability so that he became a great teacher. Without this effort the accomplishments of the great teachers would not have arisen spontaneously. We must give ourselves encouragement. As the Bodhicaryavatarasays, “Even flies and worms have within themselves the possibility of attaining buddhahood and one day will do so. So if I make an effort I will definitely attain buddhahood much faster.” If we think this way, it will act as a powerful encouragement. We always have the base for buddhahood, the only thing necessary is to make use of it.

So effort is needed, without the self-deception of postponement. Whenever we have the chance, we must make use of it immediately, and bring about a change in our mind, which will change our actions of body and speech. And then even a trivial deed of body or speech can become a powerful mental force. Everything depends greatly on the power of mind. Some deeds of body and speech which, for ordinary people, would be wrong can be transformed into virtue by someone with great power of mind. Therefore mental development is very necessary, and makes a great difference in our actions. So we must make the effort to start practicing now. We should not say, “I must do great things,” but rather start with the smallest and easiest, according to our ability. For example, everyone would like to eat very tasty food, but we just have to eat what is available, and it is stupid to starve if we cannot get the best food there is. We must start with the lesser and go on to the greater. Drop by drop an ocean is filled.

Therefore without postponing anything we should start practicing now. Which for us means Mahayana, Sutrayana, Paramitayana, and Tantrayana, the right combination. In order to practice we must first, hear, learn and know Dharma. This is why we are now learning this teaching on the Thirty-seven Practices of the Bodhisattva. So you should all listen with the motive of attaining buddhahood for all mother sentient beings, in the same way that Gautama Buddha spoke of his enlightenment 2,500 years ago. By following the bodhisattva practices, first attaining the gem of bodhicitta, then attaining an accumulation of merit, and finally attaining full buddhahood. We must go through this process, so that with that motivation, with close attention, please listen to this teaching.

Yesterday we were concerned with the opening homage. There are three parts, the beginning, main part, and ending. In the main part the first practice says we must have learning, contemplation, and meditation. The second one says that for doing this we must be in the right environment, and abandon the wrong kind, with its wrong involvements. One must, therefore, abandon one’s country. As a guru has said, “Abandoning one’s home and country, without involving oneself in bewildering busy distractions.” The idea is to free oneself from involvements, and therefore the third practice is to live in solitude.

Being in solitude, if our body, speech, and mind are still governed by worldly principles, then this is the worst state of all. It is better to live and lead a happy worldly life in the busy world. In solitude we must be able to break attachment to all happiness and wellbeing in this life. Therefore the best practice is to give up attachment to this life. Even in solitude, it is necessary that a companion or friend should be inspiring rather than a wrong one who distracts us. Therefore the fifth practice is to abandon wrong friends.

After the experience of solitude it is no longer enough to have no distractions, we must do something to eradicate illusions forever—just being peaceful is not enough. At this stage it is essential to realize shunyata and wisdom (Skt: prajna). This can be achieved only by the combination of concentration and higher insight. Mantras and prayers are not enough. It is beneficial to live virtuously without this realization, but only temporarily. For permanent serenity the uprooting of delusion by shunyata is necessary.

Therefore morality (Skt: sila), concentration (Skt: samadhi) and wisdom are required. Sila is to protect oneself, like armor in a war. The real weapon is prajna, but we must also have strength, samadhi. We must fight the enemy and destroy him, and we need to achieve this forever. Sila is like a fence to shield us, then we must develop the power of prajna and samadhi, and attack the enemy. Therefore, to nurture and develop all our virtues and qualities we must make a great effort ourselves, but also have a good instructor. We must search out good guidance, a spiritual friend or guru and then practice the proper way of following him. So the sixth practice is to hold one’s spiritual friend dearer than one’s own life.

Remember that even an ordinary teacher must be qualified, and must have a good character in order to set an example to his students. What he teaches is for this life only but he needs to be kind and wise. Someone who is a spiritual teacher must of course be far more qualified, since he is not concerned simply with this life. Therefore the guru should have the ten qualities. He should have a serene and controlled mind, a mind rich in quality, effort, and teaching. He should have clarity, thusness, compassionately wise speech, and he should have abandoned all discouragement. So we should follow a guru with such qualities, and be oneself a good disciple, have the right states of mind, the attitude of an intelligent, unselfish son, following the guru’s instructions, acting according to his wishes, being close to him in mind. If we have this reliant kind of mind, and he is truly qualified, he will seek the most helpful things for his disciple, and show the way. He will never do this in an adverse manner. And the closer we are to him the better. We must have the “pure view,” look at his qualities and kindness, and thus serve and respect him.

It is for the guru to judge the disciple, and for the disciple to judge the guru. For example, readiness for tantra must be carefully judged. So it is important that there should be a two-way process of judging. Regardless of his title, we should judge a person and then follow him properly. There is no obligation to regard the guru—or the Dalai Lama—with blind faith, you must take the time to judge the guru as appropriate, or you must abandon him. This can take a long time, even up to twelve years. So we must have complete freedom in this way, and in order to obtain the supreme freedom, we must have regular freedom first, otherwise there is a contradiction here. We have the same freedom to follow what tradition we choose, even whether we practice Dharma or not, and which dharma we practice. We must always have a broad mind, and then, sometimes, the mind will spontaneously be well controlled. It is in the nature of our mind that if we force it too much, it will react against this, but if we give it freedom, it will again come under control. We should remember that if we are to do something, we should do it exactly and properly. We should not be alarmed at the slightest doubt, nor rush off like a rabbit from a falling tree. When we fail in our practice of Dharma, we may look for an excuse by criticizing Dharma. Well, it is better not to practice than to criticize from the outside.

So having chosen a guru in complete freedom, once chosen, we should have the right attitude as a disciple. As Tsongkhapa says, “Give up self-centeredness, leave choice to the guru, let him decide, like an intelligent son’s attitude towards his father, provided he is qualified. We can’t give our nose ring to just anybody.” Of course we do not practice Dharma solely on trust, like shooting arrows at night, that kind of Dharma is not possible in this age. But Buddhadharma is not like this; everything has a base and its reasons, not just commandments and blind faith. Even in this degenerate age the radiance of the Buddha’s glory has not dimmed. Therefore the Buddhadharma is based on the right reasons. For example, we who call ourselves practitioners of the Dharma have shortcomings in our practice, but the Dharma itself is always immaculate. And it can give us the utmost benefit, show us the best and most virtuous way to live, the best kind of human being to be.

We should therefore search very carefully, judge carefully and once we have found him, we should have unswerving devotion to the guru and follow him completely. This is a brief explanation of guru devotion. Today’s teaching is about refuge.

The seventh practice of the bodhisattva:

Those gods who are themselves bound in the prison of samsara, how can such worldly gods have the ability to protect or liberate us? Therefore to take refuge in those who may always be relied upon, to take refuge in the Triple Gem – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

Those who are completely fettered by karma and delusion in samsara, for example, worldly gods or spirits, asuras, and who are reputed to have the ability to harm people and to provide a few rather slight and temporary benefits, these kinds of gods, especially in the border areas, are very popular. For example, there are village and mountain deities which have even been the object of human and animal sacrifice. Such deities are absolutely wrong, particularly those which demand the sacrifice of animals in the hope of rain and good crops. Spirits who demand this kind of evil offering are bad themselves. This is true of some oracles too. Their situation is the same as ours, they too are subject to suffering, even though they do not have a body like us and may exist in the formless realm. But like us they are subject to karma and delusions.Since they are in the same situation as ourselves there is no reason to take refuge in them. So which worldly gods can save us? As the power and ability to save are lacking in them how can they help us? For “refuge” implies hope, and they will always disappoint our hopes. Knowing that they are impotent, and still taking refuge in them, is a proof of stupidity. Before placing hopes, we should first ask whether the being concerned has the power or ability, and decide on taking refuge accordingly. So it is not worth taking refuge in impotent and worldly gods. So where is the right object of refuge, which never lets us down? This is the Triple Gem, which is the perfect refuge. To realize this is a practice of the bodhisattva.

Refuge is an important dividing line, it is this which makes a person a Buddhist or not. He who accepts the Triple Gem as the ultimate refuge from the depth of his heart and who follows it in practice, he is a true Buddhist. Someone who does not have this profound reliance, even if he has a thorough knowledge of the scriptures, and outwardly his practice seems sound, is not a real follower of the Dharma nor a Buddhist. This issue makes the distinction between the Buddhist and the non-Buddhist. There are many levels of refuge, but one who from the depth of his heart accepts the Triple Gem as the ultimate object of refuge has achieved a sufficient solution. The dividing line between followers and non-followers of the Dharma consists in this very important point. .

Now to explain the significance of the Triple Gem. The Tibetan for “buddha” means fully awakened, clear of or awakened from faults, purified from defilements or with all defilements eliminated. This refers both to defilements that are external and those due to the wrong qualities of the external world. As I explained yesterday, all defilements, of the internal and external world, are due to karma, and this in turn derives from the untamed mind produced by delusions. What is a delusion? It is a quality of mind which, when it arises in oneself, immediately agitates the mind, destroying its peace and happiness. The Tibetan word nyonmong for klesha, or defilement, means something which upsets or agitates the mind. It is a concept, a way of thinking which, when it arises within us is, because of its activity, immediately agitating. This thing which makes the mind untamed and uncontrolled is delusion, which causes karma. So the production of karma depends on whether the mind is controlled or tamed and this in turn depends on delusion. And all the various kinds of delusion we have stem from one root delusion, ignorance. So all external and internal shortcomings and defilements are produced by this process – the untamed mind resulting from delusion, in turn derived from self-grasping ignorance.

The fruit of collective karma is something rather different. But when an individual tames his mind fully the fruit of external and inner defilements is eliminated. When we refer to a buddha, that means that all his inner defilements, such as desire and hatred, have been extinguished. But it is not enough for a buddha to eliminate delusion, he must also rid himself of jneyavaranạ, the impediment to knowledge about the whole of existence. Otherwise, even great bodhisattvas have problems due to the obscuration of full knowledge.

When full knowledge, too, is obtained, his mind gains, develops, expands; his mind is fully expanded. Awakening, then, covers this whole process. So a person who has attained this ultimate goal of no defilements, with all his potentialities of knowledge fully realized, is a buddha. But such buddhahood does not come about spontaneously, it has to be developed. It is not without cause, and it is not like permanent, independent self-existence. For the Dharma teaches us that sentient beings do not remain in a static state. So all buddhas, such as Sakyamuni, who became enlightened here, were once just as we are, but gradually, by making progress on the path and getting rid of all defilements, and by developing all virtuous qualities, and by discarding defilements one by one, gaining virtues one by one, became a buddha. This abandonment of defilements and gaining of virtuous qualities is mainly achieved by the mind, which has a tremendous range of possibilities and many facets. For example, you are at present looking at and listening to me, and are cognizing something. There are different objects of cognition—color, sound, and so on. One cognition perceives all forms, another tastes all tastes, another responds to smells, another to touch, these are the five sensory cognitions.

Above them all is a cognition which people nowadays describe in various ways, such as the brain, or the sensory consciousness which sends messages to the brain. This mental cognition is the most important and is like a “king cognition,” while the senses are like ministers. Each has its own responsibility, one to see, one to hear, and so on. The conclusion of these processes takes place in the mind, and it is then that the idea comes, “I have seen,” “I have smelt,” and so on. The concept of “I” has its basis in this way. For providing the basis of this “self,” the “I,” the most important factor is thus mental cognition, the consciousness that draws conclusions.

Mental consciousness also exists at many levels: one is working now, another arises during the dream state. Growing more and more subtle, another consciousness arises with fainting. There are many levels here, the highest level being at death—we arrive at another state of consciousness then. The ultimate stage of fainting is death, when the finest and most subtle stage of mental consciousness arises. In the process of dying the coarse consciousness disappears, and outwardly death occurs with the end of breathing, but in fact life goes on and the state of the most subtle mental consciousness continues until actual death.

This state of the most subtle mental consciousness is the real nature of the mind, a nature that is completely free from all delusions, because delusions only arise and operate with the coarse level of consciousness, which has come to a stop. All conceptual cognition has already dissolved. There are thus many levels of mind, with the finest as I have explained. So the finest level of the mind is purged of defilements, which shows that these defilements are temporary. The ultimate nature of mind is unsullied by illusions—nobody is permanently angry. If hatred were a lasting thing, the mind of an angry person would be angry all the time. Though a person gets into a rage there is a time when he calms down, so hatred comes and goes, it is transient, which shows that the nonvirtuous qualities of mind are not undetachable from mind. Desire, attachment, jealousy are a completely different family. Therefore such delusions, however powerful they seem, can be gotten rid of and avoided.

To take hatred as an example: When the kind of delusion that arises towards a disagreeable object causes a desire to harm or be rid of it, this is a very crude mental state indeed. On the other hand there is loving kindness, and that, again, is a state of mind that arises towards an agreeable object, creating a feeling of closeness and goodness. So these two states of mind, these two attitudes are completely opposed to each other, and they cannot exist simultaneously. So there are many different qualities of mind, different in nature, and diametrically opposed, and they can never be simultaneous. There are different sides to the mind. The defilements, or wrong states of mind, are all backed and supported by ignorance. And because this is so, because they are supported by self-grasping ignorance, they do not have the support of valid cognition, because the grasping of self-existence is due to ignorance about the true nature of reality. It is a completely mistaken cognition, because it regards everything as existing with an independent self, whereas in reality nothing exists in this way. If we therefore judge and analyze on this basis, the more deeply we investigate concepts, the more they gradually dissolve. Generally speaking, the closer we investigate an object, the clearer it becomes. But when the object does not exist, what we had thought existed fades away. For example, if we inquire into what is said by a merely glib or “smooth” talker, we find no substance. It is the same with the ignorance which holds that everything possesses real existence. If we investigate deeply and ultimately we eventually conclude that the contrary is true, and, when we discover that, ignorance and grasping lose their power and cannot survive.

Because of illusion, mental defilements seem superficially very strong, but because they depend on a false, foolish basis, they are transitory. On the other hand, none of the virtuous mental qualities rest on such false basis. And so we have two completely different kinds of mental qualities, which can never exist simultaneously, and one of which has firm foundations and the other not. Because of this, if we try to develop qualities on the firm foundation, their opposites, lacking this foundation, must slowly fade away until completely extinguished. The more warmth and light increase, the less cold and darkness remain. The more the virtuous qualities grow, the more the defilements disappear. In the beginning both sides of qualities may receive support. For example, if nondevotion is strong, devotion grows less. The negative force can conquer in the early stage. For example, the attitude of cherishing other sentient beings may start and last for a month. This develops the attitude quite well, but if one stops, it may degenerate, because we have not built the foundation and support, which is the realization of the nonexistence of the self. Otherwise a seesawing development can happen. This is why we must practice and acquaint ourselves with a path using both method and wisdom. Then the virtuous force will not degenerate. By becoming habitual, a virtuous quality of mind will develop infinitely. So virtuous qualities develop infinitely and destroy the strength of nonvirtuous qualities. By going through such a process and attaining fully accomplished qualities and full freedom from defilements one reaches the state of buddhahood.

Such a Buddha, according to the Theravadins, is a Buddha Sakyamuni, who in the early part of his life was a bodhisattva, then attaining the stage of full enlightenment here under the bodhi tree, and becoming a buddha until his paranirvana. After paranirvana, he attained, according to the Theravadins, dharmadhatu; his stream of consciousness came to a complete end.

According to the Mahayana, this is not exactly what happened, for even though he entered paranirvana, and his own physical appearance ceased, the Buddha still exists in the dharmakaya, whereby he still manifests himself in various forms in order to help constantly sentient beings, even doing so in different worlds. So he still lives on. In this way Buddha Sakyamuni is one manifestation of his dharmakaya. According to the Mahayana, although he was born as a prince, and passed through various stages, all of these were a kind of show, and in fact he was already enlightened. The mind of such a buddha is known as the jnanadharmakaya, the most subtle state of mind which has completely eliminated all defilements and which is constantly absorbed in the ultimate nature of every existence—thusness or shunyata—and perceiving every existence simultaneously with its ultimate nature, one constantly absorbed in the ultimate nature of every phenomenon, perceiving all phenomena without and with appearance, therefore with shunyata.

That is the state of buddha mind known as jnanadharmakaya. Then there is sambhoghakaya, a physical body not coarse like our own but subtle and endowed with the previous body, a subtle buddhabody which exists until the end of samsara, and from this sambhoghakaya derivesnirmanakaya, which manifests itself in different worlds and beings. So when we say we take refuge in the Buddha, we take refuge in these three bodies. Are you clear about the meaning of refuge in Buddha?

Now about Dharma. The ultimate Dharma is the cessation of defilements and the path, which is within Buddha and those who are not yet buddhas but who are on the road to buddhahood, like the aryabodhisattvas. AryaSravakas and aryapratyekabuddhas, too, experience cessation of defilements, so they also are Dharma. Such arya beings also have the true path within them, which is the realization of shunyata, and the level of true cessation they have attained also represents ultimate Dharma, the quality of abandonment of defilements and the quality of realization of the path. This is the object of taking refuge in Dharma. Dharma is the true refuge which, when attained, frees us from certain defilements and suffering. The Dharma is the main refuge. The Sangha refers to those endowed with true cessation and the path, the Arya Sangha or Ultimate Sangha, those who have realized shunyata. So these three are the object of refuge of those who follow the Dharma.

So far we have been talking of the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha outside us, this is the causal refuge. For example, a guilty and fearful person seeks the aid of a powerful one: “I trust you, I rely on you, so help me.” Our goal must finally be to attain these stages ourselves, because that is the object of our primary wish—to be free from suffering and to obtain happiness—and this must be done within. This is because all suffering comes from karma, delusion and ignorance, and it is by gradually bringing about the cessation of these that we will bring an end to and obtain freedom from suffering. This is how we must accomplish our aim, for the existence, externally, of the Triple Gem, will not help us completely. The benefit for us of the presence of Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha is not total. We must regard the Buddha as a doctor or teacher, and trust in him and his instructions. The Dharma is a medicine we must take and we must then practice in accordance with it. Though we cannot attain ultimate Dharma immediately, we can do so eventually by developing all qualities prior to and after entering the path. Gradually we can obtain full and unfailing Dharmahood. So we must start from the base, abandoning nonvirtuous deeds.

There are three nonvirtuous deeds of the body: killing, from a human being down to insects, even mosquitoes—when they bother us we may kill them unintentionally—right down to the egg of a louse. Then comes stealing, ranging from the most valuable to the trivial items. Killing is the worst act of all because it is the most harmful to other sentient beings, and it is the heaviest in consequences. There is no excuse for killing one’s enemy from hatred, and there should be no attachment to meat, entailing the killing of a chicken or a goat, though some qualification is needed here. If an animal has already been slaughtered for sale, if you buy a little this is not a heavy unskillful deed. There are many references in the Dharma to meat, for instance in the vinaya about meat being free from the three wrong qualities. In some sūtras it is rejected completely, but this varies with the disciples and circumstances. One should not therefore deliberately kill an animal for food or have somebody else kill one, but where the animal has already been killed, eating it is permitted. Strict vegetarianism is however best. But if we stop eating meat and become weak, then we must reflect on what matters most, and if the health of the body is more important and you can use it beneficially then meat eating is permissible. But killing animals out of desire or attachment, particularly for sacrifice is wrong and very foolish, though it is popular in the borderland areas , and there must be some present who engage in it. Well, it is much better for you to stop immediately and on returning home to tell the spirits that His Holiness has told you to stop it. Say, “We do not like to stop it but His Holiness is against this and said so at Bodhgaya.” Blame it on me, and if the god is a powerful one he can come and deal with me. I make you this pledge. So that kind of destruction of life is done out of ignorance. A bloodthirsty god may be pleased, but he is not worth pleasing, he is a weak god, he can’t kill for himself and has to have others to do it for him. If he really insists on sacrifice let him do it himself.

Stealing is another unskillful deed because it harms the possessions of others, so it also causes them suffering and should be avoided. On one of these days I heard a loudspeaker announcement that “a purse has been found.” This is a very good practice. Finding a purse on the road, being ready to give it back is a good sign. Otherwise you may find something and say “I’m not doing anything wrong, this is just what I want, this is marvelous,” but if the owner has not thrown it away, you have no excuse. Actually, there have been so many broadcast appeals, I think someone will soon lose his nose here! Then there is sexual misconduct. Generally, this means adultery, intercourse with someone else’s wife. This is very bad, most of the trouble in society comes from this. From high society in developed countries down to natives in the jungle, this discord over women is a major source of trouble. Abandon the deed and such strife will cease.