His Holiness the Dalai Lama: As Ku Tung says, “Twenty years are spent without a thought for Dharma and twenty are spent saying, ‘I will practice,’ and ten more are spent saying, ‘I’m not able to practice Dharma.’ and that is the story of an empty life.”

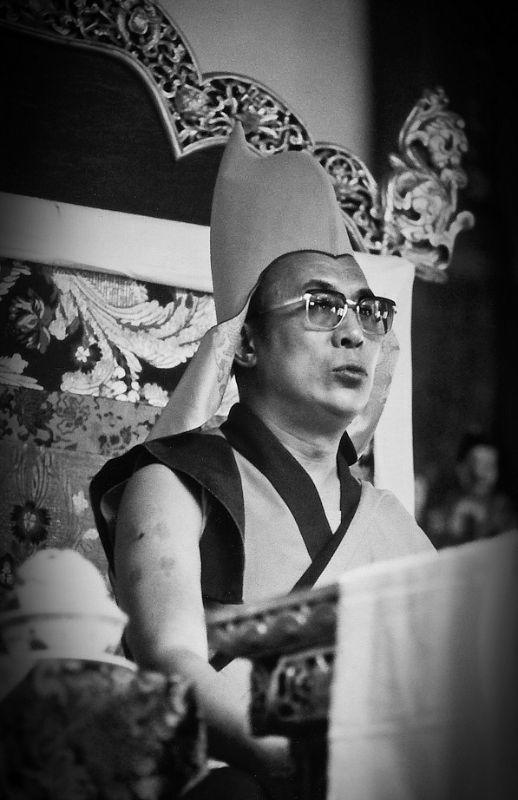

3 – The Thirty-Seven Practices of the Bodhisattva by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Bodhgaya 1974.

Therefore having this precious human birth and the time and chance with a body in perfect condition, it is not enough to stop unskillful deeds but to try our best to achieve buddhahood for oneself and others.

Now we have all the favorable opportunities – so now is the time to take them. So we must make the effort to perform this task for others and ourselves. The method is learning, contemplating and meditating on Dharma, especially Mahayana Dharma, there is nothing more we can do to further ourselves. We should make an effort to be like the flow of a river. First, acquire knowledge, ponder until we get certainty, address our mind one-pointedly to it. To concentrate and contemplate, combining the two harmoniously is a practice of bodhisattva.

Through this combination we arrive at intuitive experiencing—intellectual learning alone is not enough, contemplation and concentration are needed—then we achieve a result. Practicing Dharma is not like learning history. The purpose of learning Dharma is its practice, the practice of a bodhisattva.

The second practice of the bodhisattva:

Towards friends attachment flows like water, towards enemies the fire of hatred burns. When there is a darkness of ignorance we cannot lose attachment and practice renunciation. To abandon home and country – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

To perfect the previous practice and perform the higher ones it helps to give up one’s country or home and abandon such involvements. This is because our country and home mean relations and friends but also enemies and bad neighbors. There are many objects in our home or country to give rise to delusions on our part. When we live at home or in our country, there are frequent possibilities of attachment or aversion, all kinds of involvements with our relatives. For tulkus this can mean disciples of the previous life or previous relatives.

Although one may desire solitude, there may be a great deal of socializing. Other involvements arise with people we do not like. Praise and criticism by others, all these involvement’s arise because of being in these social circumstances. Even if somebody does not have that many friends, just a small home, there is still the darkness of ignorance about what to abandon and what to accept. Even a simple monk with no friends has a “mouse hole” to be busy in, to be house-proud of. One can see him taking an old box to it, an empty tin, a piece of rag for cleaning. It’s true, isn’t it? This is, of course, not very harmful, but it is a little harmful. Together with his little altar, he has scriptures he dusts and tidies up every day, but does not read! And of course he keeps polishing his altar bowls! If within yourself you are practicing deeply, this is all right. But if not, you are trifling time away. Small objects of attachment distract from practice.

Therefore, to abandon one’s country and home is the practice of a bodhisattva. A home is a place where there is a river of attachment flowing to one’s friends or family. This kind of attachment—delusion—is very powerful. Ignorance is at its deepest here, with its two attendants, desire and hatred. Ignorance is a king, with the worrier hatred and the collector desire. When we meet someone we don’t like, hatred comes forth, looking like an armed volunteer to defend you, to protect you, guard you, but in fact what he does is lead you to real defeat. Attachment to home and family seems loving, helping oneself very much, implying much kindness in a very sweet and peaceful way. In fact we are deceiving ourselves. Desire, hatred, ignorance remain the three most powerful poisons and delusions, and one way of countering these is to abandon home and country, that is why this is the practice of a bodhisattva.

The third practice of the bodhisattva:

By abandoning adverse surroundings delusions will gradually perish, and because there are no distractions, a virtuous practice will naturally develop, and by having a very clear mind our certainty in Dharma will grow. Thus dwell in solitude – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

Just giving up your country is not enough. We Tibetans gave up our country unwillingly. We are exiles now, but if we had made our home in a busy city, this would not have been good. Our whole aim should be to reduce attachments and delusions. In the “busy” life more and more attachments will arise again. So we must search for solitude, endowed with the many qualities mentioned in theBodhicaryavatara.

So if we live in solitude, no business-type involvements, no petty concerns, can arise. There is no one to waste time with in idle talk, our only friends are animals—not perhaps, in India, though there are beautiful birds here—with no other objects for attachments or hatred, nobody else to distract us, and with luck there will be pure clean good air and pure water.

With no distractions or involvements, inner thinking and contemplation arise spontaneously. From morning to evening we should just meditate and practice. Such solitude is very necessary, all the great gurus have trodden this path and lived in such surroundings in order to practice Dharma. Within this short life we must keep in mind that one day we will go into solitude and practice Dharma,“raising the victorious banner of meditation.”

As the mind grows clearer, our surer realization of Dharma will grow. Simply “digesting” the offerings of lay people, just eating and doing nothing to purify ourselves, is very dangerous. But when we live in solitude, there are no such offerings, no problem of “digestion”. This helps our mind to become clearer. To busy oneself with offerings and various requests can be bad. If our minds are undefiled this will be better for Dharma. When a solitary meditator returns to company for a few days, he points out the great difference of atmosphere. In solitude there are no obstacles, our thoughts are not muddied by the multitude. Therefore to retire in solitude with such qualities is a practice of bodhisattva.

In monastery life the proper spiritual response to offerings is very important. If somebody makes a big offering and we show him more respect than to our guru, this is wrong. Those in big monasteries must be very careful in these matters. When ordained, a monk’s duty is to look up to all the past buddhas and great gurus. Then, one must forego worldly gains and achievements, fighting with delusion. It is then that one becomes a real monk. Otherwise the outward change, such as a new name, makes little difference. Great care must be taken over worldly objects, the messengers of Mara.

A monk should fly off like a crow, leaving nothing—not like some monks who need three porters when they move! So a monk should remain simple and possess few objects. Tibetans in general are in special circumstances and need to have enough. But a monk should have a minimum. For a community to have resources is all right, they are needed to support all. When a community wishes to collect money it should be prudent about its fund raising activities. People will object, see no end to the process and give with the wrong motivation. People should not be pressed, and only willing gifts should be accepted. Temples, stupas and monasteries should not benefit from reluctant contributions.

A great guru wanted to go from Tibet to India. His friend said, “There is no need to go to India. Everything is within you.” We must take the middle path. When Tibetans were in Assam, we were nearly in a negative extreme, now when facilities elsewhere are better; the desire to build grows. Drepung Monastery, for example, was started for study, not just to collect offerings. Its complement of 7,700 monks was intended to enable more people to study Dharma, not just to provide catering facilities or occupy many lavatories! This was the initial intention; we must remain faithful to it.

Once a monastery is built, it should be used properly, to bring buddhahood about for other sentient beings. When all the monasteries in Bhutan, Sikkim and Lhadakh were built, people always had a high opinion of monasteries, and sometimes they were right and sometimes wrong. Now views have changed. Before, if sand and gold were mixed, people were tolerant. Times are different now, so monks must be careful, otherwise Dharma can be harmed. I am not interfering with other peoples’ affairs, but being a religious person, I give you this advice: When we teach others, we must live up to our principles. So if one is attached to worldly objects more than to spiritual ones, while teaching others to be the contrary, whose ear will this go into?

The Buddha has told us that if we teach we must practice the meaning. So all religious people must be very careful. If one can live there properly, the monastery is precious, a field of merit, and will help the whole Dharma; the monkhood is needed for this. So lay people and monks must help and relate to each other, laymen helping monks, the monks teaching Dharma, providing education and whatever else they can give. Not just for future life but with everything possible in this life. Then there will be a good relationship. So if we can, we should live in solitude, if not, in a monastery, living in a right manner, one which oneself and others can rejoice in, that is very good.

The fourth practice of the bodhisattva:

We will take leave of our closest friends who have long kept us company, the possessions and wealth obtained by much effort must be left behind, the guesthouse of our body left by our consciousness. Therefore mentally renounce attachment to this life – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

Home and country left behind, solitude now found, we now need to renounce attachment to this life. We must therefore see that life lacks substance, see this by its impermanence. Because sooner or later this life will end and we shall have to take our leave of it. If at that time we have some practice of Dharma because of the seeds of a noble mind, this can help. Besides this, there is nothing else that can. Our friends, supporters, kith and kin, cannot help, however numerous, however wealthy, it will be worthless. Even our most precious and close body which has been our constant companion must also be left. Sooner or later this situation will definitely arise, and quite unpredictably. There is no certainty in human life, we cannot have confidence in it. It is the tenth day of the Tibetan month, perhaps someone will die this evening, we cannot be sure that we will be here tomorrow. I may say, “Oh, I am young and healthy, so I shall live,” but this is not at all a good reason. We think this, but cannot be certain. There is not even 100 percent certainty that I will not die this evening. In short, all of us will die, and we do not know when. Since, at that time, only the practice of Dharma will help, if we are attached to the happiness of this life, whether for a day or a year, this is a waste of time. What we must do is prepare ourselves, whether we die soon or late, so that there will be no repentance, no regret, if life should end this evening. If we live beyond this evening there is more time to prepare for death.

This life is unimportant. We can always find a living by looking around us. When we escaped from Tibet and got to the Indian border we wondered how we were going to live, yet we can always find a livelihood in the human world. What matters is the time when we part from this world and go into an unknown, new world, about that one must be very careful. As in the Seventh Dalai Lama’s prayer, “The life beyond which is remote from all we are accustomed to, from everything experienced. In this life there is always someone to help us and show us. When we leave we must be absolutely self-supporting, to make the journey alone.” Or as the Buddha said, “I show the way of liberation, but this liberation depends on you.”

Many people come to see me and some ask me to pray to save them from the lower realms or to pray for the dead. Of course I do this, I accept this responsibility, as I am supposed to follow the bodhisattva path, I will pray from the depth of my heart, though I cannot visualize everyone. I do try to pray for the welfare of all beings and my prayer may help a little but it is difficult to say it helps deeply. But the main thing is one’s own effort, making one’s own way. One cannot rely on others to save oneself, to take one to nirvana. Everything is in one’s own hands; to reach nirvana, buddhahood, the choice is ours. Therefore it is difficult to obtain full satisfaction by praying to gurus, bodhisattvas, the Buddha. The important effort is, without wasting time on this life’s entanglements, to prepare for a long future, so that when death comes there is nothing to worry about. For this preparation Dharma practice is very important. Seeing the impermanence of worldly things will help us to renounce only worldly involvements. Then the mental energy devoted to worldly life will diminish until we renounce it by seeing its essencelessness.

The fifth practice of the bodhisattva:

If we have a companion who increases the three poisons of hatred, desire and ignorance, and diminishes our threefold practice of learning, morality and meditation, and also makes us lose our love and compassion, we should abandon such a bad friend – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

This shows the need for proper guidance, for a guru whom we can look up to. With the right guru and friends, we will progress smoothly on the path. Without a guru, or with the wrong kind of friends, our good qualities will perish. Especially for the bodhisattvayana, a friend who makes us lose love and compassion we must abandon like contagious disease, as an object of attachment, this is the practice of a bodhisattva.

The sixth practice of the bodhisattva:

By following one who will eliminate our faults and increase our qualities like a waxing moon, to hold such supreme guidance even more precious than one’s own life – this is the practice of the bodhisattva.

The necessity of following a guru and right guidance is pointed out by guru Potowa: “To attain buddhahood there is nothing more important than following a guru. Even though we can learn in this life simply by looking at others, we still need a teacher. To escape from the lower realms onto the path, it is essential to have a guru.” Therefore to improve this deluded mind, we have to find a way to know how to do this, and so we need a qualified guru with experience, someone with the full experience of that which he shows us. So just as a patient must follow a doctor’s treatment to be freed from his illness, to be freed from the illness of the three poisons we must follow our guru, this is the bodhisattva path.

Therefore the guru is someone the disciple can completely trust and rely on. He must accordingly have certain qualities. As Sakya Pandita says, “Even for a minor business deal in jewels or horses we would ask advice from many people. So in preparing ourselves forever, just to take the Dharma indiscriminately is not right.” It is the guru’s task to tell us what to accept and what to abandon, therefore it is very important to judge the qualities of the guru, to judge his quality beforehand. So we must know all his qualities beforehand in vinaya, sutras and sastras, and tantra.

Then we must follow a person endowed with most of these qualities that a guru should have. So we must search out the right kind of guru, and then found, follow him correctly. We must follow him with a pure view of him, seeing his qualities as the same as the Buddha’s, his kindness as even greater than the Buddha’s. With this view in mind we must develop a firm devotion from the depth of our heart, by seeing his qualities and kindness, and their union, and then venerate him, especially through practice. We must please him in this way. There are in fact three ways of pleasing a guru: by material offerings, service and practice. So we must venerate the guru, especially through practice. A truly qualified guru will be delighted by veneration through practice.

Remember how Marpa made Milarepa work hard, and then initiated him? Well, Marpa said: “My disciple Milarepa who has nothing to offer, and my other disciple, who has offered everything including a goat with a broken leg, between the two I have made no difference in my teaching.” Oh yes, there is a guru with the right qualities. Otherwise a guru concerned with material offerings thinks something like, “Practice is up to you, I have what I need, so I don’t care”. Sherawa says: “On his side the disciple should offer much, but the guru should never be attached to the offering. If he was, he could not be called a true guru!” Thus to follow a guru properly is the practice of a bodhisattva.

Has everyone understood well? Now let us pray to Padmasambhava for the peace and happiness of sentient beings, and the flourishing of Dharma especially in Tibet, and to the Buddha as an emanation of the perfect cause, the collection and accumulation of merits, whose mind perceives all values, relative and absolute, by remembering the Buddha’s qualities of speech, body and mind, who has instructed us with such teachings as bodhicitta, who 2,500 years ago has shown the deeds of attaining enlightenment and blessed this area. Also with this prayer develop your devotion, remembering his greatness and compassion. Our protectors of the Dharma in Tibet are in decline but signs of their power are increasing. Therefore let us pray and invoke Padmasambhava, he is their Lord and very necessary at this time.

As said in the sutra, the three worlds are as impermanent as an autumn cloud. The birth and death of beings are like a play. Our life is like lightning in the sky, like a waterfall over a cliff. All compounded phenomena, including beings and places, all are impermanent, changing every moment, in flux, never permanent or eternal. Especially the life of a person in this age is changing particularly swiftly. Since taking birth it is definite that we will die. When it comes it will be a complete surprise, like lightning when we least expect it, taking us to another world. Such a situation will surely arise but we never know when, such a state of impermanence are we in. Since the beginning of the world, before written history, with all the years that have passed, no one has escaped death. The wise, the powerful, the clever, once born, their lives end in death. In brief, each and every one of us will degenerate in the same way, with failing eyesight, hearing and so on. The body we were proud of when young will become a burden, become fatiguing to all. When we had all the perfections, people respected us, said perhaps we had the word of the Buddha, but later these too will look down upon us and turn away.

All abilities and qualities degenerate, what was an object of attachment becomes and object of aversion. We shall be full of regret that our plans have been left unfulfilled, disturbed that we have no abilities left. We shall reach a stage when no plans can be made, when there are no worldly involvements left. Early in our lives, we are young vigorous, bright, competitive, capable of “catching birds flying in the sky.” Then later we grow older, get married, have children and so on, having the responsibilities that go with this, no longer being free to do as we like, but acting according to the interests and wishes of one’s wife, children, in-laws. We must then keep up a certain status, worldly values, compete with others, feel superior to others. At first we search for just any job, then we look for one with a better salary, promotion. Then if our job is good, we start looking for better social standing. In this process with its involvements, days, months and years are spent.

Even formerly in Tibet it was like this. A monk or student went from childhood to the student stage, and of course there are many that study with the right motivation, to obtain buddhahood, but there are also many who study the scriptures with the aim of becoming a very wise man, with the motivation, “I will become a distinguished person,” or “I will get a ‘first’ as a Geshe.” They are attached to the empty title, and looking for the position of abbot of a great monastery, or even just the abbot of a small monastery!

So this is what is meant by well-being in this life. “Involvements in this life are like waves succeeding each other. One goes, another comes after it. So the more we accomplish in worldly ways, the more will accumulate. Isn’t it better to bring this to a sharp halt?” Therefore if we can suddenly stop these involvements, with the mind relying on Dharma practice, this is very beneficial. Otherwise though one’s body is wrapped in robes, with the title of abbot, one is lost in worldly principles. First there are only the disciples of one’s teaching, then many offerings come, someone has to administer these, so one’s “personal staff” begins to grow and so on. Unless our mind is internally controlled this outward show can be very dangerous. One is deluded into thinking one is practicing Dharma. Without self-awareness one may think, “I am a very good practitioner of Dharma.” But deep thought would show us we are subject to the eight worldly principles, and it is doubtful that our Dharma practice is real. Even someone who is supposed to practice Dharma and knows Dharma well does this, which shows how difficult it is for others without the same opportunities. So life can be wasted in this way. And we reach a point of wishing to practice but have no ability.

As Ku Tung says, “Twenty years are spent without a thought for Dharma and twenty are spent saying, ‘I will practice,’ and ten more are spent saying, ‘I’m not able to practice Dharma.’ and that is the story of an empty life.” In my own case, up to the age of twenty there was in me a will to learn and practice Dharma very well and there was also a little will to realize sunyata and bodhicitta. Yet these twenty years were spent without much substance, they just passed by. Then the Chinese came. I spent nine years with them. I wished to continue the study of Dharma, but a stream of troubles, and disappointments distracted me from this. So another nine years go by. Yet at nineteen I had been ordained, had taken bodhisattva vows, tantric vows. But to say that the mind’s integration of the Dharma is complete, this is difficult to say. I have lived up to the age of twenty-five with the title only of “The Victorious One,” the “Omniscient One.” So then I was twenty-five. We have lost our country. I still tried to continue studying and practicing Dharma in India, but many involvements arose again. Five or six years passed. My level of thinking has become a bit more advanced. I have come to realize that without the integration of the Dharma within the mind, just reading and reciting mantras has little substance and is self-deceiving. “If the Dharma does not become integrated with the mind, mantra recitation is a waste of our fingernails.” So with that realization I try my best, but I still find myself saying, “For twenty years I could not practice Dharma.” So whatever our outward form, or the impressions of others, the crux of the matter lies within us. One has to be “the main witness of oneself.” In order that we will not need to have regrets or repentance, we should perform a good internal “check-up,” from this we will not have to repent, to murmur regrets to ourselves.