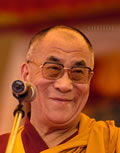

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: There’s no room for violence in a world in which we must all live together, interdependent on one another.

The Dalai Lama’s Reflections on the Realistic Approach of Buddhism: Talks to Former Dharamsala Residents from the West

His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama Dharamsala, India, November 2 – 3, 2010. Transcribed by Sean Jones and Michael Richards Edited by Luke Roberts and Alexander Berzin With clarifications indicated between square brackets. This is the printer-friendly version of: http://www.BerzinArchives.com /web/x/nav/group.html_677503622.html

Part One: Advice on Death and Dying

Leading a Meaningful Life

Firstly I want to express my greetings. Many of you, I think, are very, very old friends, longtime friends, and unchanging friends. So that’s very good.

Thirty, forty years have gone by since the time you lived and studied here. Our bodies have changed.Generally speaking, even spirituality or meditation cannot stop that from happening. We are impermanent, always changing, changing from moment to moment; and that is part of nature. Time is always moving; no force can stop that. So the real question is whether we are utilizing time properly or not. Do we use time to create more problems for others, which also ultimately makes us ourselves feel unhappy deep inside? I think that’s a wrong way to utilize time.

A better way is to try to shape our minds every day with a proper motivation and then carry on the rest of the day with that sort of motivation. And that means, if possible, serving others; and if not, at least refraining from harming others. In that respect, there’s no difference among professions. Whatever your profession, you can have a positive motivation. If our time is used in that way over days, weeks, months, years – decades, not just for five years – then our lives become meaningful. At the very least, we’re making some sort of contribution toward our own individual happy mental state. Sooner or later our end will come, and that day we’ll feel no regrets; we’ll know we used our time constructively. I think many of you use time in a proper, meaningful way. That’s important.

Having a Realistic Attitude about Death

Our present lives, however, are not forever. But to think: “Death is the enemy” is totally wrong. Death is part of our lives. Of course, from the Buddhist viewpoint, this body is in some sense an enemy. In order to develop genuine desire for moksha – liberation – then we do need that kind of attitude: that this very birth, this body, its very nature is suffering and so we want to cease that. But this attitude can create a lot of problems. If you consider death is the enemy, then this body is also the enemy, and life as a whole is the enemy. That’s going a little bit too far.

Of course, death means no longer existing, at least for this body. We’ll have to part from all the things that we developed some close connection to within this lifetime. Animals don’t like death, so naturally it’s the same with human beings. But we are part of nature, and so death is part of our lives. Logically, life has a beginning and an end – there’s birth and death. So it’s not unusual. But I think our unrealistic approaches and views about death cause us extra worry and anxiety.

So as Buddhist practitioners, it is very useful to remind ourselves daily about death and impermanence. There are two levels of impermanence: a grosser level [that all produced phenomena come to an end] and a subtle level [that all phenomena affected by causes and conditions change from moment to moment]. Actually the subtle level of impermanence is the real teaching of Buddhism; but generally the grosser level of impermanence is also an important part of practice because it reduces some of our destructive emotions that are based on feeling that we’ll remain forever.

Look at these great kings or rajahs – in the West also – with their big castles and forts. These emperors considered themselves immortal. But now when we look at these structures, it’s rather silly. Look at the Great Wall of China. It created such immense suffering for the subjects who built it. But these works were carried out with the feeling: “My power and empire will remain forever” and “My emperor will remain forever.” Like the Berlin Wall – some East German communist leader said it would last for a thousand years. All these feelings come from their grasping at themselves and their party or their beliefs and from thinking they will remain forever.

Now it is true that we need positive desire as part of our motivation – without desire there’s no movement. But desire combined with ignorance is dangerous. For example, there’s the feeling of permanence that often creates the kind of view that “I will remain forever.” That’s unrealistic. That’s ignorance. And when you combine that with desire – wanting something more, something more, something more – it creates even more trouble and problems. But, desire with wisdom is very positive, and so we need that.

We also see [reminders of impermanence] in tantric practice, with skulls and these types of things, and in some mandalas we visualize cemeteries [charnel grounds]. All these are symbols to remind us of impermanence. One day my car passed through a cemetery, so it was fresh in my mind when I mentioned it later in a public talk: “I just was passing through the cemetery. That’s our final destination. We have to go there.” Jesus Christ on the cross showed his followers that finally death comes. And Buddha did similarly. Allah, I don’t know – Allah has no form – but of course Muhammad demonstrated it.

So therefore we need to be realistic that death will come sooner or later. If you develop some kind of attitude right from the beginning that death will come; then when death actually does come, you’ll be much less anxious. So for a Buddhist practitioner, it’s very important to remind ourselves of this on a daily basis.

What to Do at the Time of Death

When our final day comes, we need to accept it and not see it as something strange. There’s no other way. At that time, someone who has faith in a theistic religion should think, “This very life was created by God, so the end is also according to God’s plan. Although I do not like death, God created it, and so there must be some meaning to it.” Those people who truly believe in a creator god should think along those lines.

Those who follow the Indian traditions and believe in rebirth should think about their future life and make some effort to create the right causes for a good future life, instead of worry, worry, worry. For example, at the time of dying you could dedicate all your virtues so your next life will be a good life. And then [no matter what our beliefs] at the time of dying, the mental state must be calm. Anger, too much fear – these are not good.

If possible, Buddhist practitioners should use their time now to look ahead to their next lives. Bodhichitta practices and certain tantric practices are good for this. According to the tantric teachings, at the time of death there’s the eight-stage dissolution of the elements – the grosser levels of the elements of the body dissolve, and then the more subtle levels also dissolve. Tantric practitioners need to include this in their daily meditation. Every day, I meditate on death – in different mandala practices – at least five times, so still I’m alive! Already this morning I’ve gone through three deaths.

So these are the methods to create a guarantee for a good next life, like that. And for nonbelievers, as I mentioned earlier, it’s important to be realistic about the fact of impermanence.

How to Help Those Who Are Dying

With those people who are actually dying, it’s good if the surrounding people have some knowledge [of how to help]. As I mentioned earlier, with those dying people who believe in a creator god, you can remind them of God. A single-pointed faith in God has at least some benefit, from a Buddhist point of view as well. With those people who have no belief, no religion, then as I mentioned earlier, be realistic, and it’s important to try to keep their minds calm.

Having crying relatives around the dying person might be detrimental to them keeping a calm mind – too much attachment. And also because of too much attachment toward their relatives, there’s the possibility of developing anger and seeing death as an enemy. So it’s important to try to keep their mental state calm. That’s important.

On many occasions [I’ve been requested to go to Buddhist hospices]. Like in Australia there’s a nunnery where the nuns are totally dedicated to taking care of dying people and those with serious illnesses. This is a very good way of putting our daily practice of compassion into action. That’s very important.

Part Two: The Meeting Point of the East and the West

Eastern Knowledge and Western Science

As for what are the meeting points between the East and the West, I think already thirty or forty years ago I mentioned on one occasion that Eastern knowledge, mainly here in India – specifically knowledge about emotions and about the mind – is quite detailed; and this is because there is the practice of samadhi [absorbed concentration] and vipashyana [an exceptionally perceptive mind]. These are not based on faith or devotion; they’re for training our minds. Naturally any teaching with the practice of samadhi and the practice of vipashyana will have an explanation about the mind: how mind works, how emotion works.

Then also in Buddhism there is prajna or wisdom [discriminating awareness], and also in Buddhism the key view is selflessness or anatma theory. So in order to debate about anatma theory, naturally you need a more detailed understanding about ignorance and about distorted views. And for distorted views, the only counterforce is right view, not prayer, not just mere meditation. Then in Tantrayana there is the discussion of the different levels of mental states – the awakened state, dream state, deep sleep state, or the state at the time of fainting. [These are all examples of Eastern knowledge about the mind.]

Of course science comes from the West. The scientists, in most cases, come from a Judeo-Christian background, so naturally they don’t pay much attention to mind and emotions and these kinds of things. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the practice level is the same [as in Eastern religions] – the practice of compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, and also contentment and self-discipline. This is the same in all the major religions. Where these religions differ is in the ways to promote these basic human values.

There are religions that are based on faith in a creator, including those Hindu traditions [that accept a creator]; and because ultimately everything depends on the creator, faith alone is sufficient. In order to reduce your self-centered attitude, you need tremendous faith in God the creator. You’re totally submitted to God. That reduces your self-centered attitude. Whereas Buddhism has no concept of a creator – also Jainism and also one part of Samkhya has no creator – therefore you yourself make effort to change your mind. It’s not possible to change these things through prayer.

People eventually developed religious faith over at least the last three or four thousand years. Whenever they met with difficulties, they would pray and put their hope in the creator or God or put their faith in Buddha. Like the Tibetans – we just put our faith in Buddha, but were negligent about our human-level actions. So that’s why we lost our own country, isn’t it?

So for the last several thousand years – I think at least four or five thousand years – people have placed their ultimate hope and faith in God. But now, over the last two centuries, science and technology have developed and begun to fulfill many of our hopes. For the last thousand years, we totally relied on faith; but now, without faith, concrete results are being produced by science and technology. People, including Eastern people, are relying on science and technology, and it’s right that many are attracted to them.

But since the later part of the twentieth century, more and more people are experiencing the limitations of having only material values. Material objects provide us with physical comforts and really give us some kind of satisfaction on a sensorial level, but not on a real mental level. If you compare mental-level experience and sensorial-level experience, mental-level experience is much more serious. We’ve all experienced that when our mental state is happy and calm, our physical pain can subdue. But physical comfort can’t subdue our mental state when we have too much mental pain, too much worry. So obviously our mental state is more serious.

More and more doctors and scientists are realizing our mental state is very, very important for our heath. A healthy mind is very much related with a healthy body. But a healthy mind can’t be produced by medicine or alcohol or drugs. A healthy mind can’t be given by injection or bought from the supermarket. A healthy mind must develop within the mind itself – from faith to some extent; but no, not really. Genuine conviction can come only through research and investigation.

So I feel the point of the East and the West meeting isn’t for religious reasons, but simply for the science of mind.

Scientific Aspects of the Nalanda Tradition

I’ve been engaged with meeting scientists for the last thirty years. At the beginning – I think forty years ago – I expressed to some of my friends that I wanted to have a dialogue with scientists. One American lady told me, “Science is the killer of religion. Be careful.” But then I thought about the Nalanda tradition. They would investigate and experiment with the teachings, and if they found any contradiction they would literally reject Buddha’s own words. Buddha himself also made clear: “None of my followers should accept my teachings out of faith, out of devotion, but rather through thorough investigation and experiment.” These masters took the liberty to carry out investigation even into Buddha’s own words. And so we have the Tibetan words drangdon (drang-don) and ngedon (nges-don) – the provisional teachings [interpretable teachings] and definitive ones. So therefore I realized the emphasis of the Nalanda tradition was on investigation rather than faith.

The whole Buddhist system is based on reality, today’s reality. The two truths [superficial and deepest] are explanations about reality. Then according to that reality, we can make the distinction of wrong view and right view. So in order to prove these are wrong views, we have to investigate what is reality. There is always a gap between appearances and reality. Many wrong views are based on appearances, and most destructive emotions come from wrong view – grasping, self-grasping. So on that basis, we have the idea of the four noble truths. Just relying on Buddha’s word, saying, “Oh, Buddha stated the four noble truths,” is wrong. We have to prove the four noble truths. We have to know the real system or structure of the four noble truths.

[See: Introduction to the Four Noble Truths.]

So therefore I realized science is also trying to seek the reality, the truth, but of course in a different field. Buddhists are also trying to seek reality. I think both are truly implementing the famous Deng Xiaoping statement: “Seek truth from facts.” Both traditions through investigation try to seek the truth, the facts. So therefore I realized there is no contradiction. The scientific way of approach, of investigation, is to keep a skeptical attitude. Buddhism is exactly the same.

Making a Distinction between Buddhist Science, Buddhist Philosophy, and Buddhist Religion

Since our meetings and conferences with scientists, some people have used the words: “The meeting of science and Buddhism,” but this is wrong. We are not discussing with scientists about Buddhism, only about Buddhist science. So I made a distinction between Buddhist science [science coming from Buddhist literature], philosophy coming from Buddhist literature, and Buddhism. So Buddhism is for Buddhists; Buddhist science and Buddhist philosophy are universal.

I feel that already there’s been some sort of meeting of East and West. Western top scientists are now really paying much attention to the value of training our minds, because this is very important and very relevant for our health, whether for society, families, or individuals. Like at Wisconsin University, under the leadership of Richard Davidson. He has already carried out some special programs about training the mind, these sorts of things; and also Stanford University, the last few years. I have just visited them. All their experiments are really wonderful research. And then Emory University. So, like that, these are nothing to do with religion. It’s simply trying to take some of the information that comes from Buddhist texts to use as a scientific method to train our minds, to strengthen the basic good qualities of our minds [like compassion and affection] that come from our mothers.

So, like that, I think that’s the proper place for the East and the West to meet. That’s my feeling. Not religion, just science.

Part Three: Buddhism in the Twenty-first Century

How to Be Twenty-first-Century Buddhists

I’m always telling the Tibetans and also the Chinese and Japanese, and the Ladakhis and all the Himalayan Buddhists – I’m always telling them that now we are in the twenty-first century, we should be twenty-first-century Buddhists. That means having a fuller knowledge about modern education, modern science, and all these things, and also utilizing modern facilities, but also at the same time having full conviction about Buddha’s teachings about infinite altruism, bodhichitta and the view of interdependency, pratityasamutpada [dependent arising]. Then you can be a genuine Buddhist and also belong to the twenty-first century.

Recently I was in Nubra [Ladakh], and I stopped on the road for lunch. Some local people came – some of them we’ve known for twenty or thirty years – and so I chatted with them. I told them that we need to be twenty-first-century Buddhists and also that study is very, very important. Then I asked them, “What’s Buddhism?” And they said, “Buddham saranam gacchami. Dharmam saranam gacchami. Sangham saranam gacchami. [I go for refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.] That’s Buddhism.” That’s too simple. Then I asked them what are the differences between Buddha, Jesus Christ, and Muhammad? They said, “No differences.” That’s not right. As far as being great teachers of humanity, they’re the same. But as far as their teachings are concerned, there’s a big difference. Buddhism is nontheistic. I asked you one day whether Buddhism is a form of atheism or not, and you mentioned that atheism means “anti-God.” Buddhism is not anti-God – Buddhism respects all religions – but Buddhism is non-theistic in the sense of there being no creator, no concept of a creator. So on the teachings side, on the philosophical side, there are big differences between Buddhism and these other religions, but these villagers felt they’re the same.

That reminds me: One time in Tibet, a lama was giving some teaching, and people asked him, “Where are the Three Jewels? Where is Buddha?” And he kept quiet for a little bit, and then he pointed at the sky and said, “Oh, the Buddha is in a crystal palace in space, surrounded by brilliant lights.” That’s not true. Buddha is ultimately here in our hearts – Buddha-nature.

So therefore I want to share with you that we must go to the real basis of Buddha-dharma [the teachings of the Buddha]. Like when you have the main food – rice or flour or, in the Tibetan case, tsampa – and then some vegetables. Beautiful vegetables; they’re very good. But without the main food, just having a few vegetables – just having a few side dishes – is not sufficient. And that’s important to understand.

The Trunk and Branches of the Tradition

I usually describe Tibetan Buddhism as being the pure Nalanda tradition [in the sense that it is heir to the teachings of the seventeen great masters of the ancient Indian monastic university of Nalanda.] That’s the basic thing. I also explain to our Buddhist groups, including those in Ladakh, about the analogy of the tree trunk and the different branches. The Nalanda tradition is like the tree trunk. Then [the Tibetan traditions of] Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, Gelug, Kadam, Jonang – all these are like the branches.

Recently I was in Dorzong center, a Drugpa Kagyu center. Their rinpoches usually have very good study programs, not only for their own monks but also for young Tibetan lay students. I asked Dorzong Rinpoche about their program, and it’s a very good one. So I explained to them there about the trunk and branches and how, as far as unity is concerned, Sakya, Nyingma, Kagyu, Gelug, Kadam, and Jonang all go to the root. There are no differences. But when there’s too much emphasis on the branches, then the little differences here and there stand out too much. These branches are important; some special things are there, like dzogchen [the great completeness] and mahamudra [the great seal] and Sakya lamdray [the path together with its results] and seltong-zungjug [the joined pair of clarity and voidness]. Each one is good, but they’re all related to the trunk. It’s very good when these special features come on top of full knowledge of the basic teachings of the trunk. Then it’s complete. But if you neglect the basic teachings and just hold these branches, then it’s not complete, and also there’s the danger of misinterpretation.

So that’s the trunk, the Nalanda masters. I usually describe seventeen Nalanda masters. Their texts are the explanations about basic Buddhism. The others are the branches.

The Importance of Skepticism

According to the trunk – the basic Buddhist teachings – skepticism is very essential. Now, I think and hope I am a Buddhist, but I no longer have any conviction in Mount Meru. The two truths and four noble truths are the real explanations for the cosmos, for the galaxies and the Big Bang. That’s the real teaching of Buddha and Buddhism.

The presentation of the classic texts is structured around the four placements of confidence. [Don’t place your confidence on the person, place it on his or her teachings; don’t place your confidence on his or her words, place it on their meanings; don’t place your confidence on their interpretable meanings, place it on their definitive meanings; (to understand them) don’t place your confidence on your dividing consciousness, place it on your deep awareness.] The classic texts mention that the real audience of these books, their serious readers, must have a skeptical attitude. They need to investigate whether the content of the book is something relevant to their lives or not. What temporary benefit does it have? And in the long run, what benefit does it have? The serious audience must be clearly aware of the relevance of the text before following its teachings.

That’s exactly the Nalanda approach. People in the audience must be skeptical. Skepticism brings questioning; questioning brings investigation; investigation brings answers. That’s the only logical approach.

Refuting Beliefs about Mount Meru and the Location of the Hell Realms

When I was in Sar Ashram forty years ago, on one occasion I mentioned, “Buddha didn’t come to this planet to make a map. So it’s not Buddhist business whether there’s a Mount Meru or not. It doesn’t matter.” Like that. So we have the liberty to reject Vasubandhu’s explanation [in Abhidharmakosha, A Treasure House of Special Topics of Knowledge]. We must make a distinction between literal and symbolic meanings. In Kalachakra it’s mentioned that Mount Meru and all these things symbolize the human body, from the head to the soles of the feet. There are many similar tantric explanations. So these symbols have a certain meaning, a certain purpose.

And about the hells, the concept of the hells: I find it very difficult to accept what Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakosha mentioned: that twenty leagues [pagtse (dpag-tshad), Skt. yojana] beneath Bodhgaya are the eight different hell realms. The pagtse is much longer than a kilometer. So if you go down further and further, then most probably the hells exist in America! But it’s disgraceful to say that America is a hell. So these things aren’t difficult to refute.

There are three ways of understanding things: through sensory perception, through inference based on reasoning, and through relying on the authority of scripture. That means [in the case of scripture] relying on a third person. I often tell people that it’s like our own birthday: We have no way to investigate what’s our real birthday. We have to rely on a third person; for example, our mother. And in order to accept the third person’s description, first we have to prove that person is honest, reliable, and has a normal mind. So we need to test some other field that the third person has mentioned, something that we can investigate. If we investigate and find it’s correct, we know this person is truthful and has no reason to lie or pretend things. Then we can accept that person’s other statements.

So, like that, there might be mysterious phenomena that are beyond our level of understanding and that we have no experience of. If there are people who say they have actually experienced these phenomena, we can check their writings and see if they are reliable concerning other points. If so, we can rely on this third person’s explanation of the things that are beyond our reasoning. We have to take this sort of approach with some of the explanations in Buddhist literature.

Now, according to pramana – logic and epistemology – [there are different types of proof and refutation. One type of refutation involves a phenomenon that should be observable, but isn’t]. For example, according to the Abhidharmakosha, the sun and moon are the same distance from Earth, and as they revolve around Mount Meru, day and night come about. Seemingly we actually experience Mount Meru’s shadow [during the night], but if we experience its shadow, then we should also be able to see the mountain. In ancient times in India, Vasubandhu didn’t have the possibility to check to see if there is a Mount Meru. But now we have spacecraft, so we should be able to see it. If Mount Meru exists, we should be able to see it. But since we cannot see it, we can say it doesn’t exist.

So there are refutations that involve not being able to observe the phenomenon you are trying to prove or where you observe the opposite of it. Dignaga and Dharmakirti clearly mentioned these things in their texts. So utilizing our own Buddhist epistemology, the nonexistence of Mount Meru is easily proved. It’s no problem to refute these things.

One time in South India, at a big gathering of student monks – I think more than ten thousand student monks (all the major monastic institutions’ students were gathered there) – I mentioned my views about the importance of science and that we must learn science, modern science. And then I mentioned that I don’t believe in Mount Meru and all these things. Then I said, “Oh, but please don’t consider me a nihilist.” On the first day my teaching was more on the relation between Buddhist science and Western science. Then the second day I explained about the Buddhist teachings. So the first day I was being more innovative in my teaching, and the second day was more traditional religious teaching. So anyway it’s no problem to refute these things.

Potential Dangers of Guru-Devotion

So now if we go to the root, there is no emphasis on the importance of devotion. But if you go to these branches, like mahamudra or dzogchen, then guru-yoga is very important. That’s actually spoiling some of these lamas, and then their centers can become cults. Why? Because of forgetting the basic Buddhist teachings and focusing just on these branches.

Like Naropa, the main teacher of Marpa, the Kagyu lineage’s main figure. Naropa was one of the great scholars of the Nalanda institution. Then later he practiced Tantrayana looking like a beggar or sadhu. Naropa only had the potential to practice these things because he studied all the important texts available in the Nalanda tradition. But now some of the practitioners in the West – among Tibetans also, among the Ladakhis also – without knowing the foundation of Buddha-dharma, do whatever their lama says. Even if their lama says, “West is east,” he or she believes: “Oh, that’s the east.” That’s against the Nalanda tradition.

Of course the person who is really fully qualified in the basic knowledge about Buddhism is different from a lama who just sits on a high throne – like me on a high throne – but whose real experience is very limited. Now it maybe looks as if I’m a little bit jealous of these lamas! But according to my experience, I think they don’t have proper, full knowledge, and they just emphasize these branches. That creates a lot of misunderstanding. That’s important to understand.

Adapting Buddhism to the West

The idea of having a Western Buddhism is perfectly all right, perfectly all right. You know that Buddhism originally came from India. Then when it reached different places, it mixed with local cultural traditions and became Tibetan Buddhism, Chinese Buddhism, Japanese Buddhism: like that.

Some of the musical instruments that our Tibetan monasteries use don’t come from the Nalanda tradition, but come from the Chinese side. There’s an instrument called a gyaling (rgya-gling) [the Tibetan shawm or oboe], literally “Chinese flute.” And in some of these monasteries, the people who play that also dress like the Chinese. Silly, isn’t it? That’s not part of Buddhism; that’s just a cultural aspect. So similarly in the Western Buddhist community, you can use modern instruments and pray to the tune of a Western song. That’s okay. That’s no problem.

But as far as the idea of the four noble truths and altruism and all these are concerned: You see, Buddhism deals with emotions, and today’s human emotions are the same as the human emotions 2600 years ago. People’s emotions have been the same for I think the last three or four thousand years and will remain the same for the next few thousand years. After ten thousand or twenty thousand years, some new shape of brain will have evolved, and then maybe things will be a little different. But that’s too far ahead. There’s no need to modify the teachings for our generation, the second generation, the third generation – it’s the same human brain and the same human emotions. You can ask scientists about this, brain specialists, and they’ll say, “Oh, it will be the same brain for at least the next few centuries. No change.” Like that. So the basic Buddhist teaching must be authentic.

One time in France I mentioned the New Age – you take something from here, something from there, something from there, and the final result is not authentic. That’s not good. I think we must keep the real Nalanda tradition. That’s very important. But cultural aspects can change.

The Problem of Misunderstanding Advanced Teachings

Now I think perhaps I have some constructive criticism. In the West I’ve met some people who know just a little bit, but who felt: “Oh, I have full knowledge!” Then, due to their own limited knowledge and misconceptions, they make up teachings. Of course among Tibetans as well this is possible, particularly those people who don’t study these big philosophical texts.

There’s one example that I think I can share with you. I visited San Francisco immediately after a great earthquake. My driver at that time was not from the State Department. It was a private car, and the driver was one of the Dharma center’s members who practiced dzogchen. I casually asked him, “When the great earthquake happened, what did you feel?” And he said, “Oh, it was a great opportunity to practice dzogchen, because it was a shock, a great shock.”

But to be in a state of shock with no thoughts – if he felt that was genuine dzogchen practice, then I think it would be quite easy: get hit and you can practice dzogchen! Dzogchen is not that easy. I myself have practiced dzogchen. Oh, it’s very difficult, very difficult.

There’s a saying: “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” There’s a little bit of truth there, so be careful. Study. And don’t rely on a lama’s instruction; rely on these authentic books. That’s important. Don’t rely on my word. Study these authentic texts written by Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, all these Buddhist masters. The teachings have been tested through centuries by those scholars. Arya Asanga wrote and argued with some other philosophers. For example, some of Nagarjuna’s writing was criticized a little by Arya Asanga; and then another master analyzed Arya Asanga’s work and criticized it. These great texts written by these masters were experimented with and tested through centuries, so they are really reliable.

And then there’s the doha, the spiritual songs [the spontaneous spiritual songs of accomplished masters]. These very individual practitioners, like Naropa or Tilopa, thoroughly studied the Nalanda tradition. Then, through practice, they gave up all worldly life, including monastic life, and completely lived as mendicants and yogis. And then through their own experiences, they composed these poems according to their own deep understanding and simple words. So there is a danger of misunderstanding these if a person knows only the basic tradition [and no further.]

The Nyingma tradition describes a system of nine yanas [vehicles]. The first three yanas – the shravaka-yana, pratyekabuddha-yana, and bodhisattva-yana [the three sutra vehicles] – are based mainly on the understanding of the four noble truths. And then the three next yanas – kriya, upa, and yoga [vehicles related to the three outer classes of tantra] – emphasize the practice of cleanliness. And then the last three yanas – maha, anu, and ati [vehicles related to the three inner classes of tantra] – emphasize the practices for controlling one’s mind.

The real meaning behind these last three yanas is to allow the emotions to develop and then, rather than becoming enslaved by that emotion, your main mind is able to look at the ultimate nature of the emotion. That’s clear light. So in these last three yanas, the destructive emotions are not seen as something that you have to overcome, but you look at the nature of these destructive emotions and see the reality. So this is on the basis of deeper experience, and it’s a very different sort of practice to that of the earlier stages. So some of the teachings from high level practitioners who have already passed through these stages are difficult to practice on our level. These nine stages aren’t easy.

Should We Act in the Name of Humanity or in the Name of Buddhism?

Recently I was in Patna, Bihar State. They made a huge construction of a Buddhist vihara, a Buddhist temple. They acquired some relics from different Buddhist countries, and I also offered them some relics. At that function, the chief minister mentioned that due to Buddha’s blessings, Bihar state will progress rapidly. Then I told him – because I know him, he’s a very close friend – “If Buddha’s blessings can help to develop Bihar state, it would have developed much earlier, because Buddha’s blessings were already there. Until an effective chief minister comes, development will not take place. Buddha’s blessings must go through a human’s hand.”

Prayer has no real effect, although prayer is something very nice but doing something is different, isn’t it? Real effect requires action. That’s why Buddhism says, “Karma, karma.” Karma implies “action.” So we must be active.

Action should be taken with the belief: “I’m one of nearly seven billion human beings. I have the responsibility to take serious concern about the well-being of nearly seven billion human beings.” Like that. When we offer a Buddhist prayer, we always say it’s for all sentient beings. No Buddhist says prayers only for Tibetans. Never pray that way. Or for just this world – there are infinite worlds, infinite sentient beings. And then we must implement that; otherwise our prayer becomes hypocrisy. Praying on the basis of a big “we,” but having our actual karma – our actual “actions” – based on a strong feeling of “we” and “they” is hypocrisy.

Now, should our actions be done in the name of humanity or in the name of Buddhism? If you try to promote basic human values on the basis of Buddhist teachings, then it becomes narrow and it cannot be universal. India’s thousand-year-old tradition involved pluralism in all religions, and it was secular – no preference of one particular religion; respect all religions. Besides the homegrown religions, all the major world religions eventually settled in India. So for the last at least two thousand years, all major world religious traditions have lived together in this country. So naturally, because of that reality, they developed secular ethics. That’s very good. There are so many religions that we can’t place stress on religious faith. So therefore the only practical, realistic way is without touching on religion – just simply secular ethics.

I’m a fully committed Buddhist. If someone shows an interest in Buddhism, sometimes I feel happy; but I never try to propagate Buddhism. Religious faith is an individual’s business. Secular ethics is the business of all human beings. So we, the Buddhist community – beside your own daily practice as a Buddhist – should think more along these lines.

I really appreciate the work of our Christian brothers and sisters. I think they’ve made the greatest contribution to education on this whole planet. You don’t see any other religion doing that. Recently in India the Ramakrishna Movement is doing something [in the area of mass education], but all the other religious groups remain in their own temples and collect money. You see, we must be active in promotion of a better, healthier society. On that level, I think our Christian brothers and sisters have done a tremendous service to human beings. But in the meantime, they also carry out missionary work, conversion work, and that’s a complication.

One time in Salt Lake City, the Mormons invited me to their headquarters. I met their leaders, and then later I gave a public talk there. I mentioned that when missionary workers go to areas where there is no solid religious tradition, then it’s good to convert the people there to Christianity. When there’s no solid philosophy there already, it’s very good. But in areas that already have solid religious beliefs, conversion creates clashes and difficulties.

Sometimes they provide money when they carry out these conversions. When each conversion takes place, they give fifteen dollars. Mongolians are quite clever about this: they undergo conversion every year, and so each year they get fifteen dollars!

Part Four: Western Society from a Buddhist Perspective

Religion

As far as religion is concerned, I always make clear to you Westerners that it’s better to keep your own traditions. Of course out of millions of people there are some individuals, like you, who… Well, I think some of you in the sixties were like hippies – a little bit confused about your own minds and having a bit of a rebellious attitude towards the existing situation, including towards your Western religious faiths, isn’t it? So you went here and there and here and there, as if you didn’t have any direction, and eventually you found some new ideas in Buddhism. So okay, if you really feel this is something useful, something helpful, then that’s okay.

Like the Tibetans – more than 99% are Buddhist, but at the same time there are Muslims among the Tibetans, and I think since the twentieth century some Christians are also there. So it is possible. Among Westerners with a Judeo-Christian sort of background – and to some extent with Islam as well – some of them find their own tradition not very effective, and they choose to be nonbelievers. Being a little bit restless on the mental level, they find some benefit in the Buddhist teachings about training their minds, and so they decide to follow that. That’s okay. That’s an individual’s right.

Education

As a Buddhist, or even any sort of person, we need to be realistic. An unrealistic approach brings disaster, so we must be realistic. I think the very purpose of education is to help us reduce the gap between appearances and reality. So many unrealistic feelings develop because of the gap between appearances and reality. We have human intelligence, and so, yes, we need education. The very purpose of education is that our minds should be wise, should be reasonable, should be realistic. The real purpose of education is that we should be realistic about all of our life, all our goals. Even with destructive goals, like the terrorists – in order to achieve their goals, their methods must be realistic; otherwise they might die before their goal is achieved. Any human action must be realistic.

Now there’s an economic crisis. There was too much speculation without knowing exactly what would happen and then pretending things are okay. Sometimes these people knew what was going on, but they deliberately showed a different picture to the public. That’s immoral. So it was out of ignorance and out of greed. According to some of my friends, that was part of the cause of the global economic crisis. If people had told the truth openly and transparently right from the beginning, then when that final announcement came, the public wouldn’t have been so shocked. They should have made it very clear right from the beginning. But now things are very difficult, aren’t they? So we must be realistic about all of our life. And then also of course in international relations, and also in environmental issues, or in any field – in any and every way, we need to be realistic.

Modern education has one thing lacking, and that’s teachings about warm-heartedness. But now there are some institutions, some universities, actually carrying out some research work into this. They’ve carried out experiments with students: If they have some short meditation to train their minds about compassion as part of their daily study, it can make a difference after eight weeks of training. So anyway that’s one aspect.

Health

Compared with animals and other forms of life, we are very fortunate to have human bodies, because we have this marvelous brain – we have the ability to develop infinite altruism and we have the ability to investigate ultimate reality. Any form of life with a less sophisticated brain than humans have has no ability to do that. All ordinary sentient beings are slaves of ignorance. Only the human brain has the ability to know the faults of this ignorance. So therefore the human body is something precious, and so we need to protect this life. For a thousand years, all we could do was to pray to some of these deities that are supposed to bless us with longevity. But now we have modern medicine and exercise, including yoga exercise, and this also is very useful to protect this precious body, isn’t it? It’s like that.

Economics

Of course my knowledge is very limited in this field. Firstly, Karl Marx’s economic theory – I was very much attracted toward the point in his economic theory concerning the equal distribution of wealth. That’s moral ethics; whereas capitalism doesn’t talk about that, just how to make profit. Therefore, as far as socioeconomic theory is concerned, I am still a Marxist.

The so-called “socialism” that was practiced in the former Soviet Union and in the early period of modern China – and in some other socialist countries – their economies eventually faced stagnation. That’s a fact. So Western capitalism is a more dynamic force as far as economic development is concerned. Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, China sacrificed its Marxist economic practice and voluntarily followed capitalism. Now, I don’t think one can blame the capitalist system for all the difficulties China is facing today. I think a free country can follow capitalism [without those problems], but [for that] at the same time you need an independent judiciary and a free press. If the media follows a principal of transparency, the elected government can be held accountable. So with capitalism, we need other methods to make society more balanced.

Now China is just capitalism – no independent judiciary, no free press, no accountability. The judiciary is controlled by the party, the economy is controlled by the party, and the press is controlled by followers of the party. So that’s the main reason why China is facing problems now. There’s immense corruption, and there’s no proper method to control these things. Poor people who are involved in corruption are given death sentences, but people in higher positions are above the law. So that’s the reason.

When the Berlin Wall collapsed, the former Eastern European countries got their freedom – for example, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. I was the first visitor, I think, to the Czech Republic, on the invitation of President Havel, and then I also visited the Baltic states, and also Hungary and Bulgaria. I’ve never been to Romania, but I visited the former Yugoslavia – Kosovo, Croatia and Slovenia. When I first visited the Czech Republic, I said, “Now is the right time to carry out more research work. Take the good parts of the socialist system, take the good parts of capitalism, and it might be possible to synthesize a new economic system.” So I said this, but those just became empty words. But of course I have no knowledge of economics.

Materialistic Lifestyles

I briefly mentioned Western lifestyles yesterday. And it’s not just Western – there’s a more materialistic society now in India too, isn’t there, a more materialistic community? They seek their enjoyment through the windows of the senses – drama, movies, music, good food, good smells, and good physical sensations, including sex. So they are just seeking satisfaction through external means, through the sensory level.

The ultimate source of inner satisfaction, however, is through training our minds, not through relying on these sensory experiences. Our contaminated [tainted] actions need to stop. Their contamination is not due to the environment; our actions become contaminated because of wrong views or ignorance. Therefore in order to stop the contaminated karma that causes our problems, firstly we must remove the ignorance here in our heads. That’s the Buddhist way. And as I mentioned earlier, academic centers are now more and more feeling the importance of taking care of our emotions, of our minds. This is a very healthy sign.

Nevertheless, it’s still better to be able to say, “My life is very nice.” Buddhism also mentions that and for this, there are the four excellent factors for a good life (phun-tshogs sde-bzhi) [(1) higher rebirth, (2) pursuit of resources, (3) teachings, and (4) liberation]. The first two factors of excellence are a higher rebirth or just a human rebirth, and then there are the necessities – wealth, property, companions, etc. for achieving a happy life, a good life. You need facilities, and for that you need money. And so money is mentioned there. But then in the long run, our goal should be nirvana – a permanent cessation of this ignorance and these destructive emotions. So that’s the permanent solution, and for that we need the practice of Dharma.

The Gap between the Rich and Poor

And then another problem is the gap between the rich and poor. This is a very serious matter. When I was in Washington at a big public gathering, I said, “This is the capital of the richest country, but in the suburbs in Washington there are many poor people and poor families. This is not only morally wrong, but also the source of many problems.” Like the September 11th events – this also is connected with that huge gap. The Arab world remains poor and their natural resources are exploited to the maximum by the West, and so the public there sometimes feels it’s unfair.

These are very, very complicated situations. I think the Buddhist community must also take some action. At least try to take care of the people in your neighborhood; mentally give them some hope, some self-confidence.

I often tell my Indian friends, those of the so-called “low caste,” the followers of Dr. Ambedkar – many of them are Buddhists – I am always telling them that this gap between rich and poor must change. Instead of slogans and displays of frustration, the poorer sections of the people must build self-confidence that they are the same. I tell them, “Brahma created these four castes from his four heads. But it’s the same Brahma, isn’t it?” So we must all be equal.

I always insist on education for the poorer section of the people. The richer section, wealthier section, needs to provide them with facilities – education, training, and equipment – to enable them to improve their living standards. I’ve also expressed this in Africa on a few occasions. It’s very difficult for the southern world. The northern world usually has surpluses. The southerners don’t even have the basic necessities. But all these people are the same human brothers and sisters.

Human Rights

Another thing I wanted to share with you is that we put too much emphasis on the importance of secondary level things – nationality, religious faith, caste – these sorts of things. In order to bring some benefit at the secondary level, we’re forgetting the basic human level. That is a problem. I think, unfortunately, like at the Copenhagen Summit [2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference], the important nations take more interest about their national interests rather than global interests; so that’s why we are facing many unnecessary problems.

We must make every effort to educate people that we are the same human beings. Then our number one priority should be basic human rights. The concerns of different nations and religious communities are on the secondary level. Like with China – I am always telling people, “China, no matter how powerful, is still part of the world. So in the future, China will have to go along with world trends.” Like that.

We must consider these now nearly seven billion human beings on this planet just like one entity, one big human family. I think that’s something we really need. But we can’t do it through preaching, but only through education and by using common sense. That’s very important.

War

When we talk about a happy humanity, a peaceful humanity, a more compassionate humanity, we must make an effort to look for the real answer to these terrorists and to the use of military force. In today’s reality, everything is interdependent. Europe’s economy and Europe’s future depends on Asia and the Middle East. America likewise. And also China’s future depends on the rest of Asia and the rest of the world. That’s the reality. So according to that reality, we can’t make a demarcation and say, “This is an enemy. This is a friend.” There is no solid basis for the demarcation of enemies and allies. So according to today’s reality, we must create the feeling of a big “We” rather than “we” and “they.”

In ancient times, a thousand years ago, this solid basis of “we” and “they” was there. And on that basis, according to that reality, the destruction of your enemy – “they” – was your victory. So the concept of war is part of human history. But now, today, the reality of the world is completely new, so we must consider every part of the world as part of “We.” We have to take serious concern about their well-being. There’s no room for violence in a world in which we must all live together, interdependent on one another.