H.H. Dalai Lama: I am basically optimistic. And I see four reasons for this optimism. First, at the beginning of this century, people never questioned the effectiveness of war, never thought there could be real peace. Now, people are tired of war and see it as ineffective in solving anything.

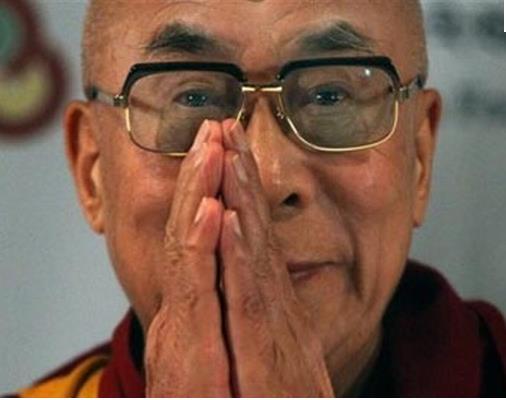

The Dalai Lama on China, hatred, and optimism —

A conversation with Robert Thurman

When the Dalai Lama Accepted the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize for his work on global human rights — particularly for his ceaseless efforts to free his country from Chinese rule — he referred to himself as “a simple monk from Tibet.” But His Holiness is also the spiritual and political leader of 6 million Tibetans, who believe him to be the 14th earthly incarnation of the heavenly deity of compassion and mercy. Like his 13 predecessors, he works for the regeneration and continuation of the Tibetan Vajrayana branch of Buddhist tradition.

Born in 1935, Tenzin Gyatso was recognized at the age of 2 as the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, and by age 19 he was negotiating with China’s Mao Tse-tung over the future of Tibet, which China invaded in 1950 and has occupied ever since. After years of failed peace talks and a violent suppression of Tibet’s resistance movement in which tens of thousands of Tibetans died, the Dalai Lama fled in 1959 to Dharamsala, India, where he continues to be the spiritual leader of Tibet’s people and heads Tibet’s government-in-exile.

Robert A. F. Thurman was ordained a Buddhist monk in 1964 by the Dalai Lama. He is currently the Jey Tsong Khapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University. A respected scholar and translator of Tibetan and Sanskrit, Thurman is also the author of Essential Tibetan Buddhism (HarperSanFrancisco, 1996) and the forthcoming Inner Revolution: The Politics of Enlightenment (Riverhead Books, 1998). As the co-founder and president of Tibet House New York, Thurman has worked closely with the Dalai Lama on making Buddhism accessible to Americans and on educating the West about Tibet’s political struggles against China. Today, Buddhism is flourishing in America: The religion has an estimated 1.5 million followers. Meanwhile, Tibet has captured the attention of Hollywood through Richard Gere and other celebrity Buddhists who have helped raise money for and awareness about Tibet’s plight. This fall a pair of films about Tibet’s spiritual and political history — Kundun, directed by Martin Scorsese, and Seven Years in Tibet, starring Brad Pitt — hit the screens.

The following conversation took place at His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s home in Dharamsala in August.

Robert Thurman: Is there something about America that makes so many people seek out and practice Buddhism?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama: I don’t know. Why are you so interested? [Laughs] No, seriously, I feel that Americans are interested because they are open-minded. They have an education system that teaches them to find out for themselves why things are the way they are. Open-minded people tend to be interested in Buddhism because Buddha urged people to investigate things — he didn’t just command them to believe.

Also, your education tends to develop the brain while it neglects the heart, so you have a longing for teachings that develop and strengthen the good heart. Christianity also has wonderful teachings for this, but you don’t know them well enough, so you take interest in Buddhism! [Laughs] Perhaps our teachings seem less religious and more technical, like psychology, so they are easier for secular people to use.

Thurman: Some people say that you have to follow the religions of your own culture. Is it really a good idea to adopt a religion or spiritual practice foreign to one’s culture?

Dalai Lama: I always say that people should not rush to change religions. There is real value in finding the spiritual resources you need in your home religion. Even secular humanism has great spiritual resources; it is almost like a religion to me. All religions try to benefit people, with the same basic message of the need for love and compassion, for justice and honesty, for contentment. So merely changing formal religious affiliations will often not help much. On the other hand, in pluralistic, democratic societies, there is the freedom to adopt the religion of your choice. This is good. This lets curious people like you run around on the loose! [Laughs]

Thurman: Your Holiness has said that in the future, when Tibet is free, you would cease to be the head of the government of Tibet. Is this because you would like to introduce the democratic principle of the separation of church and state to your nation?

Dalai Lama: I firmly believe democratic institutions are necessary and very important, and if I remained at the head of government, it could be an obstacle to democratic practice. Also, if I were to remain, then I would have to join one of the parties. If the Dalai Lama joins one party, then that makes it hard for the system to work.

Up to now my involvement in the Tibetan freedom struggle has been part of my spiritual practice, because the issues of the survival of the Buddha Teaching and the freedom of Tibet are very much related. In this particular struggle, there is no problem with many monks and nuns, including myself, joining. But when it comes to democratic political parties, I prefer that monks and nuns not join them — in order to ensure proper democratic practice. The Dalai Lama should not be partisan either, should remain above.

Finally, personally, I really do not want to carry some kind of party function. I do not want to carry any public position.

Thurman: But how about serving like the king of Sweden or the queen of England — as a constitutional Dalai Lama? As a ritual head, serving a unifying role? Would you consider this, if the people requested it?

Dalai Lama: [Laughs heartily] I don’t think so. I don’t want to be a prisoner in a palace, living in such a constricted way — too tight! Of course, if there were really serious consequences if I did not accept, then of course I would do whatever was necessary. But in general I really prefer some freedom. Maybe, just maybe, I would like to become a real spiritual teacher, a working lama!

Thurman: You’ve said you have a “comparatively better heart now” due to your exile. What has exile done for you?

Dalai Lama: When we meet real tragedy in life, we can react in two ways — either by losing hope and falling into self-destructive habits, or by using the challenge to find our inner strength. Thanks to the teachings of Buddha, I have been able to take this second way. I have found a much greater appreciation of Buddhism because I couldn’t take it for granted here in exile. We have made a great effort to maintain all levels of Buddhist education; it has helped us have a kind of renaissance, really.

Thurman: In the current conflict in Sri Lanka between the Buddhist majority and the separatist Hindu Tamil Tigers — a conflict that has claimed thousands of lives since it began 14 years ago — many have found ways to justify the continuing involvement of Buddhists, including Buddhist clergy, in the violence. Essentially, the argument is that the kind of pacifism you advocate doesn’t work in the real world, and that to let the enemy destroy Buddhist monuments and temples and kill Buddhists without fighting back is simply intolerable.

The loss of your own nation to China has been used as an example of the futility of nonviolence and tolerance. When is something worth fighting for?

Dalai Lama: This is hard to explain. In our own case, we don’t consider the loss of a monastery or a monument the end of our entire way of life. If one monastery is destroyed, sometimes it happens. Therefore, we don’t need to respond with desperate violence. Although under particular circumstances, the violence method — any method — can be justified, nevertheless once you commit violence, then counterviolence will be returned. Also, if you resort to violent methods because the other side has destroyed your monastery, for example, you then have lost not only your monastery, but also your special Buddhist practices of detachment, love, and compassion.

However, if the situation was such that there was only one learned lama or genuine practitioner alive, a person whose death would cause the whole of Tibet to lose all hope of keeping its Buddhist way of life, then it is conceivable that in order to protect that one person it might be justified for one or 10 enemies to be eliminated — if there was no other way. I could justify violence only in this extreme case, to save the last living knowledge of Buddhism itself.

For Tibetans, the real strength of our struggle is truth — not size, money, or expertise. China is much bigger, richer, more powerful militarily, and has much better skill in diplomacy. They outdo us in every field. But they have no justice. We have placed our whole faith in truth and in justice. We have nothing else, in principle and in practice.

We have always been a nation different from the Chinese. Long ago we fought wars with them. Since we became Buddhist, we have lived in peace with them. We did not invade them. We did not want them to invade us. We have never declared war on China. We have only asked them to leave us in peace, to let us have our natural freedom. We have always maintained that our policy is nonviolence, no matter what they do. I only escaped from Tibet because I feared my people would resort to desperate violence if the Chinese took me as their prisoner.

Thurman: How does one counteract violence without hatred or anger?

Dalai Lama: The antidote to hatred in the heart, the source of violence, is tolerance. Tolerance is an important virtue of bodhisattvas [enlightened heroes and heroines] — it enables you to refrain from reacting angrily to the harm inflicted on you by others. You could call this practice “inner disarmament,” in that a well-developed tolerance makes you free from the compulsion to counterattack. For the same reason, we also call tolerance the “best armor,” since it protects you from being conquered by hatred itself.

It may seem unrealistic to think we can ever become free from hatred, but Buddhists have systematic methods for gradually developing a tolerance powerful enough to give such freedom. Without mutual tolerance emerging as the foundation, terrible situations like those of Tibet and Sri Lanka, Bosnia and Rwanda, can never be effectively improved.

Thurman: You use the term “cultural genocide” to describe what China is doing in Tibet but have suggested that Tibet could live with self-rule within China. How do you define self-rule, and what are its advantages over independence?

Dalai Lama: Today, due to the massive Chinese population transfer, the nation of Tibet truly faces the threat of extinction, along with its unique cultural heritage of Buddhist spirituality. Time is very short. My responsibility is to save Tibet, to protect its ancient cultural heritage. To do that I must have dialogue with the Chinese government, and dialogue requires compromise. Therefore, I’m speaking for genuine self-rule, not for independence.

Self-rule means that China must stop its intensive effort to colonize Tibet with Chinese settlers and must allow Tibetans to hold responsible positions in the government of Tibet. China can keep her troops on the external frontiers of Tibet, and Tibetans will pledge to accept the appropriate form of union with China.

Because my main concern is the Tibetan Buddhist culture, not just political independence, I cannot seek self-rule for central Tibet and exclude the 4 million Tibetans in our two eastern provinces of Amdo and Kham. [Once part of an independent Tibet, Amdo is now known to the Chinese as Qinghai; Kham has been divided into the Chinese provinces of Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan. — Eds.]

I have been clear in my position for quite a while, but the Chinese have not responded. Therefore, we are now in the process of holding a referendum on our policy among all the Tibetan community in exile and even inside Tibet, to check whether the majority thinks we are on the right track. I am a firm believer in the importance of democracy, not only as the ultimate goal, but also as an essential part of the process.

Thurman: To your mind, once self-rule is achieved, who should be in charge of the economic development of Tibet — the Chinese or Tibetans?

Dalai Lama: Tibetans must take full authority and responsibility for developing industry, looking from all different perspectives, taking care of the environment, conserving resources for long-term economic health, and safeguarding the interests of Tibetan workers, nomads, and farmers. The Chinese have shown interest only in quick profits, regardless of the effect on the environment, and with no consideration of whether a particular industry benefits the local Tibetans or not.

Thurman: What is the environmental condition of Tibet today, 47 years after the Chinese invasion?

Dalai Lama: The Chinese have clear-cut over 75 percent of our forests, thereby endangering the headwater regions of their own major rivers. They have overharvested the rich resources of medicinal herbs and caused desertification of our steppes through overgrazing. They have extracted various minerals in environmentally destructive ways. Finally, in their frenzied effort to introduce hundreds of thousands of new settlers into south central Tibet, they are threatening to destroy the ecosystem of that rich barley-growing region by draining its major lake to produce hydroelectric power.

Thurman: What do you think it will take for China to change its policy toward Tibet?

Dalai Lama: It will take two things: first, a Chinese leadership that looks forward instead of backward, that looks toward integration with the world and cares about both world opinion and the will of [China’s] own democracy movement; second, a group of world leaders that listens to the concerns of their own people with regard to Tibet, and speaks firmly to the Chinese about the urgent need of working out a solution based on truth and justice. We do not have these two things today, and so the process of bringing peace to Tibet is stalled.

But we must not lose our trust in the power of truth. Everything is always changing in the world. Look at South Africa, the former Soviet Union, and the Middle East. They still have many problems, setbacks as well as breakthroughs, but basically changes have happened that were considered unthinkable a decade ago.

Thurman: You speak about how the Buddha always emphasized the rational pursuit of truth. “He instructed his disciples to critically judge his words before accepting them. He always advocated reason over blind faith.” Coming from a late 20th-century belief that there is no Truth, only contingent truths, how are we to imagine what the Buddha meant by “truth” in contemporary terms?

Dalai Lama: Buddha was speaking about reality. Reality may be one, in its deepest essence, but Buddha also stated that all propositions about reality are only contingent. Reality is devoid of any intrinsic identity that can be captured by any one single proposition — that is what Buddha meant by “voidness.” Therefore, Buddhism strongly discourages blind faith and fanaticism.

Of course, there are different truths on different levels. Things are true relative to other things; “long” and “short” relate to each other, “high” and “low,” and so on. But is there any absolute truth? Something self-sufficient, independently true in itself? I don’t think so.

In Buddhism we have the concept of “interpretable truths,” teachings that are reasonable and logical for certain people in certain situations. Buddha himself taught different teachings to different people under different circumstances. For some people, there are beliefs based on a Creator. For others, no Creator. The only “definitive truth” for Buddhism is the absolute negation of any one truth as the Definitive Truth.

Thurman: Isn’t that because it is dangerous for one religion to consider it has the only truth?

Dalai Lama: Yes. I always say there should be pluralism — the concept of many religions, many truths. But we must also be careful not to become nihilistic.

Thurman: How do you feel about the state of the world as we approach the 21st century?

Dalai Lama: I am basically optimistic. And I see four reasons for this optimism. First, at the beginning of this century, people never questioned the effectiveness of war, never thought there could be real peace. Now, people are tired of war and see it as ineffective in solving anything.

Second, not so long ago people believed in ideologies, systems, and institutions to save all societies. Today, they have given up such hopes and have returned to relying on the individual, on individual freedom, individual initiative, individual creativity.

Third, people once considered that religions were obsolete and that material science would solve all human problems. Now, they have become disillusioned with materialism and machinery and have realized that spiritual sciences are also indispensable for human welfare.

Finally, in the early part of this century people used up resources and dumped waste as if there were no end to anything, whereas today even the smallest children have genuine concern for the quality of the air and the water and the forests and animals.

In these four respects there is a new consciousness in the world, a new sensitivity to reality. Based on that, I am confident that the next century will be better than this one.

Thurman: Do you see Tibet as part of that new century?

Dalai Lama: Of course, of course. We are working as hard as we can; we are preparing ourselves as carefully as we can; we fully intend to make our contribution to the world in the coming century. FONT By Robert Thurman, http://motherjones.com/politics/1997/11/dalai-lama?page=1, November/December 1997 Issue