The Last Dalai Lama? By Pankaj Mishra Dec. 1, 2015 NY Times.

The Last Dalai Lama? By Pankaj Mishra Dec. 1, 2015 NY Times.

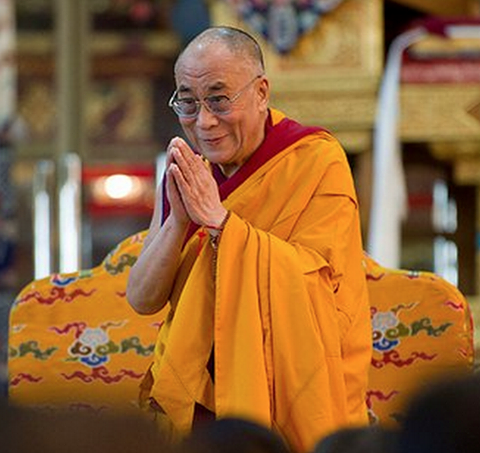

At 80, Tenzin Gyatso is still an international icon, but the future of his office, and of the Tibetan people, has never been more in doubt.

On a wet Sunday in June at the Glastonbury Festival, more than 100,000 people spontaneously burst into a rendition of ‘‘Happy Birthday.’’ Onstage, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, blew out the solitary candle on a large birthday cake while clasping the hand of Patti Smith, who stood beside him. The world’s most famous monk then poked a thick finger at Smith’s silvery mane. ‘‘Musicians,’’ he said, ‘‘white hair.’’ But ‘‘the voice and physical action,’’ he added in his booming baritone, ‘‘forceful.’’ As Smith giggled, he went on: ‘‘So, that gives me encouragement. Myself, now 80 years old, but I should be like you — more active!’’

The crowd, accustomed to titanic vanity from its icons — Kanye West declared himself the ‘‘greatest living rock star on the planet’’ the previous night — looked uncertain before erupting with cheers and claps. The Dalai Lama then walked into the throng of celebrities wandering about backstage, limping slightly; he has a bad knee. He looked as amused and quizzical as ever in his tinted glasses when Lionel Richie approached and, bowing, said, ‘‘How are you?’’ ‘‘Good, good,’’ he replied, clasping Richie’s hands.

When the Dalai Lama entered his dressing room, I stood up hurriedly, as did the Tibetan monk who was sitting beside me. ‘‘Sit, sit,’’ he said and then noticed a black-and-white photo of naked young men and women dancing during Glastonbury’s earliest days. He turned to me with a mischievous smile, and said, ‘‘Please sit and enjoy the photo.’’ He then spoke in rapid-fire Tibetan to the monk, cackling with delight: ‘‘These pleasures,’’ he said, ‘‘are not for us.’’

And yet here he was in his crimson robes — ‘‘just a simple Buddhist monk,’’ as he describes himself — among Britain’s extravagantly costumed young revelers in a 900-acre bacchanal in the muddy heart of the English countryside, inconceivably remote from the mountain passes, high plateau and rolling grasslands of his Tibetan homeland. For much of his 80 years, the Dalai Lama has been present at these strange intersections of religion, entertainment and geopolitics. In old photos, you can see the 9-year-old who’d received the gift of a Patek Phillipe watch from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Another twist of the kaleidoscope reveals him tugging at Russell Brand’s shaggy beard, heartily laughing with George W. Bush in the White House or exhorting you to ‘‘Think Different’’ in an advertisement for Apple.

Though the Dalai Lama has yet to use a computer, the 1990s ‘‘Think Different’’ ad is a reminder that he was a mascot of globalization in its early phase, between the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the terrorist attacks of 9/11. In that innocent era, the universal triumph of liberal capitalism and democracy seemed assured, as new nation-states appeared across Europe and Asia, the European Union came into being, apartheid in South Africa ended and peace was declared in Northern Ireland. It could only be a matter of time before Tibet, too, was free.

The Dalai Lama still travels energetically around the world while frequently joking about his age (‘‘Time to say, ‘Bye-bye!’ ’’). His Twitter, Facebook and Instagram accounts help secure his place in the contemporary whirl. But the cause of Tibet, once eagerly embraced by politicians as well as entertainers, has been eclipsed in the post-9/11 years. The world has become more interconnected, but — defined by spiraling wars, frequent terrorist attacks and the rapid rise of China — it provokes more anxiety and bewilderment than hope. The Dalai Lama himself has watched helplessly from his residence in Dharamsala, a scruffy Indian town in the Himalayan foothills, as his country, already despoiled by Mao’s Cultural Revolution, is coerced into an equally breakneck modernization program directed from Beijing.

The economic potency of China has made the Dalai Lama a political liability for an increasing number of world leaders, who now shy away from him for fear of inviting China’s wrath. Even Pope Francis, the boldest pontiff in decades, reportedly declined a meeting in Rome last December. When the Dalai Lama dies, it is not at all clear what will happen to the six million Tibetans in China. The Chinese Communist Party, though officially atheistic, will take charge of finding an incarnation of the present Dalai Lama. Indoctrinated and controlled by the Communist Party, the next leader of the Tibetan community could help Beijing cement its hegemony over Tibet. And then there is the 150,000-strong community of Tibetan exiles, which, increasingly politically fractious, is held together mainly by the Dalai Lama. The Tibetan poet and activist Tenzin Tsundue, who has disagreed with the Dalai Lama’s tactics, told me that his absence will create a vacuum for Tibetans. The Dalai Lama’s younger brother, Tenzin Choegyal, was more emphatic: ‘‘We are finished once His Holiness is gone.’’

The Tibetan feeling of isolation and helplessness has a broad historical basis. By late 1951, as many of Europe’s former colonies in Asia and Africa were aspiring to become nation-states, China’s People’s Liberation Army occupied Tibet. Not long after, giant posters of Mao Zedong appeared in front of the Potala Palace in Lhasa, the seat of the Dalai Lama, traditionally the most powerful leader of the Gelugpa order of Tibetan Buddhism and the spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet.

Previous Dalai Lamas held political authority over a vast state — twice the size of France — that covered half of the Tibetan plateau and was supported by an intricate bureaucracy and tax system. But the Chinese Communists claimed that Tibet had a long history as a part of the Chinese motherland. In truth, a complex and fluid relationship existed for centuries between Tibet’s Dalai Lamas and China’s imperial rulers. In the early 1950s, the Tibetans, under their very young leader, the current Dalai Lama, failed to successfully press their claims to independence. Nor could they secure any significant foreign support. India, newly liberated from British rule, was trying to develop close relations with China, its largest Asian neighbor. The United States was too distracted by the Korean War to pay much attention to cries of help from Tibet.

The Dalai Lama had little choice but to capitulate to the Chinese and affirm China’s sovereignty over Tibet. In return, he was promised autonomy and allowed to retain a limited role as the leader of the Tibetan people. He traveled to Beijing in 1954 to meet Mao Zedong and was impressed by Communist claims to social justice and equality.

But the Chinese program to uproot ‘‘feudal serfdom’’ in Tibet soon provoked resentment. In 1956, armed rebellion erupted in eastern Tibet. By then, the Central Intelligence Agency had spotted Tibet’s potential as a base of subversion against Communist China. The Dalai Lama’s second-oldest brother, Gyalo Thondup, helped the C.I.A. train Tibetan guerrillas in Colorado, among other places, and parachute them back into Tibet. Almost all of these aspiring freedom fighters were caught and executed. (Gyalo Thondup now accuses American cold warriors of using the Tibetans to ‘‘stir up trouble’’ with China.) China’s increasingly brutal crackdown led to a big anti-Chinese uprising in Lhasa in 1959. Its failure forced the Dalai Lama to flee.

He made a perilous crossing of the Himalayas to reach India, where he repudiated his previous agreement with Beijing and established a government in exile. The Dalai Lama quickly warmed to his new home — India was revered in Tibet as the birthplace of Buddhism — and adopted Mahatma Gandhi as an inspiration. But his Indian hosts were wary of him. Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian prime minister, was committed to building a fraternal association with Chinese leaders. He dismissed the Dalai Lama’s plan for independence as a fantasy. The C.I.A. ceased its sponsorship of the Tibetans in exile around the time that Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, reached out to Mao Zedong in the early 1970s. Though Western diplomatic support for the Dalai Lama rose after the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, it declined again. By 2008, Britain was actually apologizing for not previously recognizing Tibet as part of China.

The Tibetan homeland, meanwhile, has been radically remade. The area once controlled by the Dalai Lama and his government in Lhasa is now called the Tibet Autonomous Region, although roughly half of the six million Tibetans in China live in provinces adjoining it. The Chinese have tried extensive socioreligious engineering in Tibet. In 1995, Chinese authorities seized the boy the Dalai Lama identified as the next Panchen Lama, the 11th in a distinguished line of incarnate lamas. The Chinese then installed their own candidate, claiming that the emperors of China in Beijing had set up a system to select religious leaders in Tibet. (The whereabouts of the Dalai Lama-nominated Panchen Lama are a state secret in China. It is possible that, if freed from captivity, he would follow the example of the Karmapa, a lama who represents another Buddhist tradition in Tibet, who, though officially recognized by the Chinese authorities, escaped to India in 1999.)

Chinese authorities claim that Tibet, helped by government investments and subsidies, has enjoyed a faster G.D.P. growth rate than all of China. Indeed, Beijing has brought roads, bridges, schools and electricity to the region. In recent years, it has connected the Tibetan plateau to the Chinese coast by a high-altitude railway. But this project of modernization has had ruinous consequences. The glaciers of the Tibetan plateau, which regulate the water supply to the Indus, Brahmaputra, Mekong, Salween, Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, were already retreating because of global warming and are now melting at an alarming rate, threatening the livelihoods of hundreds of millions. Lhasa, the forbidden city of legend, is a sprawl of Chinese-run karaoke bars, massage parlors and gambling dens. The pitiless logic of economic growth — which pushed Tibetan nomads off their grasslands, brought Han Chinese migrants into Tibet’s cities and increased rural-urban inequality — has induced a general feeling of disempowerment.

In recent decades, Tibetan monks and nuns have led demonstrations against Chinese rule. The Communist Party has responded with heavy-handed measures, including: martial law; forced resettlement of nomads; police stations inside monasteries; and ideological re-education campaigns in which dissenters endlessly repeat statements like ‘‘I oppose the Dalai clique’’ and ‘‘I love the Communist Party.’’ Despair has driven more than 140 people, including more than two dozen Buddhist monks and nuns, to the deeply un-Buddhist act of public suicide.

As if in response to these multiple crises in his homeland, the Dalai Lama has embarked on some improbable intellectual journeys. In 2011, he renounced his role as the temporal leader of the Tibetan people and declared that he would focus on his spiritual and cultural commitments. Today, the man who in old photos of Tibet can be seen enacting religious rites wearing a conical yellow hat — in front of thangkas, or scrolls, swarming with scowling monsters and copulating deities — speaks of going ‘‘beyond religion’’ and embracing ‘‘secular ethics’’: principles of selflessness and compassion rooted in the fundamental Buddhist notion of interconnectedness.

Increasingly, the Dalai Lama addresses himself to a nondenominational audience and seems perversely determined to undermine the authority of his own tradition. He has intimated that the next Dalai Lama could be female. He has asserted that certain Buddhist scriptures disproved by science should be abandoned. He has suggested — frequently, during the months that I saw him — that the institution of the Dalai Lama has outlived its purpose. Having embarked in the age of the selfie on a project of self-abnegation, he is now flirting with ever-more-radical ideas. One morning at his Dharamsala residence in May this year, he told me that he may one day travel to China, but not as the Dalai Lama.

The Dalai Lama lives in a heavily guarded hilltop compound in the Dharamsala suburb known as McLeod Ganj. Outsiders are rarely permitted into his private quarters, a two-story building where he sleeps and meditates. But it is not difficult to guess that he enjoys stunning views of the Kangra Valley to the south and of eternally snowy Himalayan peaks to the north. The cawing of crows in the surrounding cedar forest punctuates the chanting from an adjacent temple. Any time of day, you can see aging Tibetan exiles with prayer wheels and beads recreating one of Lhasa’s most famous pilgrim circuits, which runs around the Potala Palace, the 17th-century, thousand-room residence that the Dalai Lama left behind in 1959 and has not seen since.

To reach the modest reception hall where the Dalai Lama meets visitors, you have to negotiate a stringent security cordon; the Indian government, concerned about terrorists international and domestic, gives the Dalai Lama its highest level of security. There is usually a long wait before he shuffles in, surrounded by his translator and aides.

I first saw the Dalai Lama in the dusty North Indian town Bodh Gaya in 1985, four years before he won the Nobel Peace Prize. Speaking without notes for an entire day, he explicated, with remarkable vigor, arcane Buddhist texts to a small crowd at the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment. Thirty years later, at our first meeting, in May of last year, he was still highly alert; a careful listener, he leaned forward in his chair as he spoke. When I asked him about the spate of self-immolations by Buddhist monks in Tibet, he looked pained.

‘‘Desperation,’’ he replied. But the important thing, he stressed, was that the self-immolators do not harbor hatred for the Chinese. ‘‘They can also kill a few people with them,’’ he said, ‘‘but they are nonviolent.’’

He then quickly reminded me that he had renounced his political responsibilities, ending a four-century-old tradition according to which the Dalai Lama exercised political as well as spiritual authority over Tibetans. As part of his democratic reforms, an elected leader of the Tibetan government in exile now looks after temporal matters; he also deals with diplomatic and geopolitical issues. ‘‘My concern now,’’ the Dalai Lama said, ‘‘is preservation of Tibetan culture.’’

He told me that he was not against modernization. For instance, the high-altitude railway from the Chinese coast to Tibet could bring all kinds of benefits to Tibetans. It depended on what the Chinese intended to achieve. Then, pointing a finger at me, he said, ‘‘Perhaps, also to strike fear in Indian hearts!’’ and began to laugh.

I laughed, too, though I was slightly disconcerted by his quick alternation between seriousness and levity. I was to discover over the next months that proximity to the Dalai Lama, his weirdly egoless but world-historical solidity, provokes unease, bewilderment and skepticism, as well as admiration. He embodies an ancient spiritual and philosophical tradition that enjoins a suspicion of the individual self and its desires, and stresses ethical duties over political and economic rights. At the same time, he represents — and cannot but represent, despite his recent avowals — a stateless people in a world defined by nation-states, pursuing those very interests and rights. The Dalai Lama’s life can seem one long, heroic effort to resolve the contradictions of being both a committed monk and a reluctant politician.

Born Lhamo Dhondup in a family of farmers in the northeastern Tibetan province Amdo, he was 2 when a search party of monks identified him in 1937 as the reincarnation of the recently deceased 13th Dalai Lama. Taken from his mud-and-stone house to the Potala Palace, he had barely assumed full political authority when the P.L.A. invaded Tibet.

It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of Tibetans were killed in the 1950s and ’60s, and the Communists who destroyed Tibet’s temples and monasteries were as ferocious, by all accounts, as the iconoclasts of radical Islam are today. Yet the Dalai Lama appears wholly untouched by bitterness and self-pity — the sense of victimhood that fuels many contemporary battles for territory, resources and dignity.

Indeed, even as he seems the paragon of saintly forgiveness, he advances a claim to ordinariness. ‘‘I am a human being like any other,’’ I heard him repeat in several public appearances over the last year. In Tibet, he told me, too many superstitious beliefs had overlaid Buddhism’s commitment to empirically investigate the workings of the mind. Tibetans believed that he ‘‘had some kind of miracle power,’’ he said. ‘‘Nonsense!’’ he thundered. ‘‘If I am a living god, then how come I can’t cure my bad knee?’’

He similarly asserted his nonsupernatural qualities at the summit meeting of Nobel Peace Prize winners in Rome this December. When the city’s former mayor asked him how he coped with jet lag, the Dalai Lama, Newsweek reported, gave a frankly nonreligious explanation. He could train his mind to sleep well, he said (he goes to bed at 7 p.m. and wakes at 3 a.m. to meditate). ‘‘Traveling the world — time difference — no problem,’’ he added, ‘‘but bowel movement does not obey my mind. But this morning, thanks to your blessings — after 7 o’clock, full evacuation. So now I am very comfortable.’’

The Dalai Lama works hard to establish a sense of intimacy with his listeners, usually by goading and teasing them. At Princeton last fall, he gave a talk on secular ethics to more than 4,000 students and staff members while sporting the university’s orange cap (droll headgear often leads his attempts at informality). He broke often into his conversation-stopping laughs. His audience, not accustomed to his rapid swings between mirth and thoughtfulness, remained largely earnest.

A solemn hush fell when a student asked the Dalai Lama for the key to happiness. The Dalai Lama seemed to ponder the question. And then in his noun-stressing baritone he declaimed:

‘‘Money!’’

‘‘Sex!’’

The crowd, misled by his meaningful pause, was again slow to catch up with the Dalai Lama, who had thrown his head back and started on one of his long and deep laughs. Asked for his views on investment banking, he repeated three of his favorite words, ‘‘I don’t know.’’ In order to answer the question, he said, he would have to work for a year in an investment bank. Then, with excellent timing, he added, ‘‘With that high salary!’’

Facing eclectic audiences — atheists and Muslims, hedge-funders and Indian peasants, the American Enterprise Institute and left-wing activists — he makes no attempt to appease. He often informs conservative audiences in America, ‘‘I am Marxist’’ (and he is one — at least in his critique of inequality). He has also declared himself a true jihadi in his everyday struggle against ‘‘destructive emotions.’’ In Washington this February, he told a startled group of American Muslims that ‘‘George Bush is my friend,’’ before revealing that he wrote to him immediately after 9/11 pleading for a measured response and later chided him for prolonging the cycle of violence.

The scale of the Dalai Lama’s loss and displacement primes you for a more recognizably human reaction than this endless conciliation: Tibet should remain part of China; today’s enemies are tomorrow’s friends; all existence is deeply interconnected; and the other homilies that form part of his ‘‘secular ethics.’’ And while you certainly don’t expect the Dalai Lama to match his description by Chinese functionaries — one apparatchik memorably characterized him as ‘‘a wolf wrapped in robes, a monster with a human face and an animal’s heart’’ — even those who agree with Desmond Tutu that he is ‘‘for real’’ cannot fail to acknowledge his failure as a political negotiator.

The Dalai Lama’s readiness to compromise has not prompted more concessions from the Chinese. Tibet — rich in minerals (copper, zinc, iron ore) and the site of several nuclear missile bases — may simply be too valuable a territory for the Chinese to barter away to a powerless monk. The Tibetan diaspora, denied the rights of citizenship in India, has fragmented, spreading out from its Indian base into Europe and North America. Some of its members have long criticized the Dalai Lama’s decision to settle for autonomy within China rather than full independence, a demand he publicly abandoned in the late 1980s. More militant sectarian divisions have also opened up. The Dalai Lama is stalked wherever he goes these days by drumbeating protesters shouting, ‘‘False Dalai Lama, stop lying!’’ They belong to the International Shugden Community, part of a Buddhist sect that accuses the Dalai Lama of ostracizing worshipers of the deity in Tibetan mysticism known as Dorje Shugden, as well as, more bizarre, of being a Muslim.

And the Dalai Lama’s willingness to settle for ‘‘genuine autonomy’’ within China — an enhanced Tibetan hand in policies that affect Tibetans’ education, religion, environmental conditions and demographics — has failed to convince the Chinese that he is not a ‘‘splittist,’’ or secessionist. Formal talks between the Dalai Lama and China, which were renewed in 2001, went nowhere before ending in 2010. Informal discussions continue, and there is talk, much of it from the Dalai Lama, of his making a pilgrimage to Mount Wutai, a Buddhist site in China. There is a broad hope among the Tibetan establishment that such a visit could pave the way for the Dalai Lama’s permanent return to Tibet. In the final paragraph of his memoirs, ‘‘The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong,’’ Gyalo Thondup, a longstanding emissary between the Dalai Lama and Chinese leaders, recounts a meeting in which his younger brother urges him to stay healthy. ‘‘We have to return home together,’’ the Dalai Lama says. It seems more likely, however, that China will wait for the Dalai Lama to die in exile rather than risk his politically fraught return home.

The prospect of a world without the Dalai Lama has created a new set of quandaries for the Tibetan community in exile, even as it still looks to him for guidance. A decade ago, I visited Dharamsala to research an article for this magazine about young Tibetans disaffected with the Dalai Lama’s leadership. They belonged to the 35,000-member Tibetan Youth Congress, a traditional advocacy group for independence. At the time, the most prominent among this new generation of Tibetan activists was the poet Tenzin Tsundue. He staged protests in Indian cities during state visits by Chinese premiers and was subsequently barred by the police from traveling in India. Lately, though, the pressures on him have come not from the Indian government, Tenzin Tsundue told me, but from the Tibetan establishment in Dharamsala, which discounts Tibetans demanding independence as ‘‘anti-Dalai Lama.’’ In Tenzin Tsundue’s assessment, the Dalai Lama is trying hard to signal to the Chinese that he speaks for all Tibetans in his bid for autonomy: ‘‘ ‘Independence is impossible,’ he has said. ‘Why should someone waste his or her energy on insisting on independence?’ ’’ Tenzin Tsundue told me that the T.Y.C. had split under the weight of this official disapproval.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

The current president of the youth congress, Tenzing Jigme, is a rock musician who spent 15 years in the United States. I met him at the Moonpeak Cafe in Dharamsala. On the winding road before us, narrowed by carts vending turquoise and coral jewelry, was the cosmopolitan multitude that every visiting journalist rhapsodizes about: crimson-robed monks, longhaired travelers on motorcycles, Tibetan women in brightly striped chubas, Sikh day-trippers, Kashmiri carpet-sellers and English, German and Israeli backpackers. But the adventure of globalism, it emerged from my conversation with Tenzing Jigme, had curdled here no less than in Lhasa. Dharamsala receives fewer seekers of Eastern wisdom from the West than it did a decade ago. Mindfulness is now commonly accepted as a boost to corporate efficiency. And Indian real estate speculators seem to be thinking differently by covering the hills around the Dalai Lama’s residence with cement.

The flow of refugees from Tibet, once running into the thousands, has slowed to a trickle. Many exiles have returned to Tibet, where urban and rural incomes have risen. And life for ordinary Tibetans in Dharamsala remains a struggle. They still cannot own property, and an increasing number hope to emigrate to the West. (Many of the young T.Y.C. activists I interviewed in 2005 have scattered across the world.) The United States is a favored destination; some Tibetans are doing very well there, but many have ended up working as dishwashers and janitors. Others became vulnerable to visa racketeers.

Among the elite, accusations of corruption and nepotism have further roiled the close-knit Tibetan exile community. In the latest scandal, Gyalo Thondup accused his sister-in-law’s father of siphoning off the Tibetan government in exile’s gold and silver. His sister-in-law denied the accusations in a widely circulated Facebook post.

Tenzing Jigme did not blame the Dalai Lama for these setbacks. In fact, he credited him with ‘‘the democratic shift in the community,’’ the advent of elected leaders. ‘‘He keeps preparing us for the future,’’ he said. But there was no doubt, he added, that the Tibetans faced a political impasse. The possibility that many would lapse into violence after the Dalai Lama dies had only grown.

One institution that hopes to forestall this bleak future is the Tibetan government in exile, now known as the Central Tibetan Administration. At the Dalai Lama’s residence this spring, I met with Lobsang Sangay, who in 2011 was elected the political head of the C.T.A. An imposing figure in his late 40s, Lobsang Sangay is the first Tibetan to attend Harvard Law School, and also the first nonmonk to rise high in the Tibetan hierarchy. Once a member of the youth congress and an advocate of independence, he now performs the delicate job of emphasizing the advantages of the ‘‘middle way’’ — autonomy under Chinese rule.

He was more sanguine than Tenzing Jigme, even buoyant, and seemed invested in old-style realpolitik. A year ago, he told me that he hoped the new Indian government of assertive Hindu nationalists would stand up to China. This expectation seemed to have been fueled, at least in part, by the Tibetan community’s diplomatic setbacks in the West. The Dalai Lama was scheduled to visit Oslo in May 2014 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of his Nobel Peace Prize, but even the president of Norway’s Parliament, who once headed its pro-Tibet committee, declined to meet him. Lobsang Sangay was incredulous. ‘‘This is in Norway, an oil-rich country! It is clear that China wants the West to kowtow.’’

When I saw him again in late May this year, Lobsang Sangay said he hoped China would learn from its struggles with growing anti-mainland-Chinese sentiment in Taiwan and Hong Kong and reconsider its policy in Tibet. This seems a common expectation among the Tibetan establishment, though it is not much shared outside it. The Dalai Lama told me that the Chinese ‘‘are facing a kind of dilemma.’’ In Tibet, ‘‘they tried their best to obliterate, like Tiananmen event, but they failed.’’

In the meantime, it was imperative, Lobsang Sangay told me, for Tibetans to remain united. Tibetans, he said, needed to keep in mind four key points: survive, sustain, strengthen and succeed. Briskly, Lobsang Sangay sketched a vision in which Tibetans grow richer and more resourceful through private entrepreneurship. He said, ‘‘Mahatma Gandhi, after all, received blank checks for his activism from big Indian businessmen.’’

The C.T.A.’s previous leader, a senior Buddhist monk named Lobsang Tenzin but better known as Samdhong Rinpoche, also insists on the middle way with the Chinese and is also a self-professed Gandhian. (He is one of the Dalai Lama’s closest political advisers.) Only Tenzin Choegyal, the Dalai Lama’s younger brother and the most influential of his relatives, dissents from the establishment line. T.C., as he is known, is robustly skeptical of both C.T.A. leaders. ‘‘Lobsang Sangay,’’ he said, ‘‘is already preparing for his next election.’’ Samdhong Rinpoche, he told me, was too rigid.

T.C. trained as a monk — he was discovered to be a rinpoche, or incarnate lama — before relinquishing his robes; his bold public statements have made him the enfant terrible of the Tibetan community in exile. Autonomy, he told a French newspaper recently, would give the Tibetans one foot in their homeland. They would then use the other foot to kick out the Chinese. The Chinese media quickly seized upon these remarks as proof of the Dalai Lama’s perfidious ‘‘splittism.’’

I first met T.C. in February this year, at one of the Dalai Lama’s freewheeling public talks on secular ethics in Basel. Thousands of people — some Tibetans, but a majority of them Europeans — packed the St. Jakobshalle. The Dalai Lama sat on the stage with Basel’s mayor, who looked very awkward wearing a Tibetan khatag over his suit. The Dalai Lama repeated many of the things I heard him say at other venues: It was up to the young to strive for peace in the new century. If that seemed unrealistic, then they should ‘‘forget about it.’’ ‘‘My generation,’’ he said, ‘‘is 20th century. Our time is gone. Time to say, ‘Bye-bye.’ ’’ Asked during the Q. and A. if he planned to reincarnate, the Dalai Lama boomed, ‘‘No!’’ Abruptly, he leaned toward his interpreter and asked in Tibetan, ‘‘What is the topic of this talk?’’

T.C. turned to me and murmured, ‘‘His Holiness is getting more forgetful with age!’’

A dead ringer for his brother, with the same high cheekbones, sharp eyes and kindly expression, T.C. speaks English with an Anglo-Indian lilt, a result of his boarding-school education and stint in the Indian military. As the Dalai Lama spoke, T.C. grew gloomier. He was convinced the Tibetans had no future. Tibetans were far from secure in India; they could be asked to leave any time by the Indian government. The various incarnate lamas in exile who made money off gullible Westerners were sectarian at heart, as were the Shugden. He did see some signs of hope, however. The Chinese president, Xi Jinping, was supposedly rethinking his stance on Tibet. The Dalai Lama had enjoyed friendly relations with his father in Beijing. Also, Xi’s wife is Buddhist and has visited Lhasa. Did I know that the wife of a senior Chinese leader had an affair with a restaurant owner there?

I did not. I remarked on the number of Tibetans in Basel. (Tibetans began to settle in Switzerland in the 1960s.) Many of the volunteers controlling the crowd in the arena, I learned, were hedge-funders and bankers. One of them turned out to be T.C.’s own son. In general, T.C. said, the small Tibetan diaspora had flourished in their host societies.

Cut off from both Tibet and Dharamsala, the Tibetans in the West can be extra-zealous in their devotion to their cherished leader. During the Q. and A., a member of Shugden was able to say no more than ‘‘Millions of Shugden people — ’’ before Tibetan volunteers snatched away his microphone and quickly bundled him out of sight. The Dalai Lama went on to explain his position yet again, which is, broadly, that he had not banned but merely expressed his disapproval of the Shugden deity. I told T.C. that it would have been better to let the Shugden member speak. T.C. agreed. Shugden members, he said, ‘‘want His Holiness to lose his cool. But it won’t happen.’’

For two days, Basel was enlivened by thousands of Tibetan expatriates in brilliant crimson sashes and brocade jackets. They waited for the Dalai Lama outside his hotel, keeping warm in the bone-chilling cold by singing and dancing, their exuberant drums drowning out the Shugden protesters chanting, ‘‘False Dalai Lama, stop lying!’’

Inside the arena one evening, the Dalai Lama started his speech with an effort to reconcile his audience to their displacement. He confessed that the last time he traveled there, he promised he would be in Tibet soon. But Switzerland was also ‘‘the land of the snows.’’ And, he added, ‘‘it feels like I am there. We are all from the land of the snows, not just those who were born in Tibet but also those born here.’’

He then gave a pep talk of sorts. Tibetans should be proud of themselves, he said. They and their culture were now respected all over the world. Modern science was validating the insights of Tibetan Buddhism and confirming Tibetan medicine’s assumptions about the indivisibility of body and mind. Millions of Chinese were also attracted to Tibetan Buddhism. But it was important for Tibetans not to grow complacent, to preserve their ‘‘moral culture of compassion.’’

By the time the Dalai Lama left the arena, making his way through the large assembly of Tibetans — chatting, holding hands, bumping foreheads with babies — most people had moist eyes. The Tibetans gathered here were the Dalai Lama’s devoted people, those he had held together and led, Moses-like, into the modern world. His speech made clear that, to him, Tibet had become more than a geographical and political entity; it was now a noble idea, a different way of being in the world. Its fulfillment did not require political sovereignty, let alone nationalist passion. It could be realized in any part of the world and was available to anyone, Tibetan or not.

Cynics might argue that the Dalai Lama has lapsed into a woolly internationalism; others, that his motives are pragmatic: He must constantly improvise to appear conciliatory to the Chinese, on whom Tibet’s future depends. (As Tenzin Tsundue told me, the Dalai Lama has lately invested his faith in Xi Jinping. But Xi has only hardened his stance on Tibet. So now the Dalai Lama says that ‘‘many Chinese are Buddhists, and will bring change in China.’’)

But neither cynicism nor pragmatism entirely explains his stance. It may be that he is trying to actualize the insights he has gathered as a global nomad in his post-Tibet existence — that he has transmuted his own homelessness into a vision of freedom that accords with the Buddhist emphasis on change and impermanence. Over the previous months he had expressed various versions of a drastic prospect: The institution of the Dalai Lama had outlived its purpose, he said. ‘‘If it is not needed, then do away with it.’’

A few months after we met in Basel, I went to see T.C. at his secluded hillside home in Dharamsala, a 15-minute walk from the Dalai Lama’s residence. A modern two-story building, it overlooks the British-built bungalow where the Dalai Lama’s mother used to live and which is now a guesthouse. Sitting in his book-lined study, T.C. seemed more despondent than he did in Basel. There had been, he reported, no initiative on Tibet from Xi Jinping, and early signs from India’s Hindu nationalist government were alarming. ‘‘I am really scared,’’ he said. An August 2014 meeting between the Dalai Lama and the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, was a cloak-and-dagger affair. The Dalai Lama was ushered into the prime minister’s official residence in Delhi at night, and in secret. ‘‘As if His Holiness is some kind of criminal,’’ T.C. said indignantly. Modi then proceeded to ask ‘‘insulting’’ questions: Why, for instance, was the Dalai Lama organizing a meeting of religious leaders in Delhi?

‘‘As a Tibetan,’’ T.C. said, ‘‘I am very hurt over this.’’ The Dalai Lama had been for decades the ‘‘best ambassador’’ for India, publicizing the virtues of Indian philosophy and culture. T.C. was also mortified by his elder brother Gyalo Thondup’s book and its denunciation of the Tibetan establishment. ‘‘Why write a book like that?’’ The Tibetan elites were already floundering. ‘‘You look at our directors and ministers; they are not spiritually grounded.’’

T.C. spoke for a bit on what seems his favorite subject: the ills of organized religion, as distinct from private spirituality. The Dalai Lama system, too, was ‘‘pretty reactionary.’’ He then added, ‘‘Tell His Holiness that I said this.’’

When I arrived at the Dalai Lama’s residence the next morning, those waiting for an audience lined the long driveway: Mongolian monks, Swedish backpackers and recently arrived Tibetan refugees. Flanked by a retinue that I had come to recognize — two close aides, a translator, a senior monk or two, bodyguards — the Dalai Lama patiently, even energetically, clasped their hands and posed for photos.

He chuckled when I told him that his younger brother thought his high office was past its sell-by date. Then, quickly becoming serious, he added that all religious institutions, including the Dalai Lama, developed in feudal circumstances. Corrupted by hierarchical systems, they began to discriminate between men and women; they came to be compromised by such cultural spinoffs as Sharia law and the caste system. But, he said, ‘‘time change; they have to change. Therefore, Dalai Lama institution, I proudly, voluntarily, ended.’’

‘‘So,’’ he concluded, ‘‘it is backward.’’

We sat in his reception room, flanked by his aides and an interpreter he turned to whenever he lapsed into rapid Tibetan. He sought his translation services frequently after I asked if he expected to travel to China. It was, he said, the ‘‘main request’’ of all Tibetans. He was ready, he said, if he was invited. ‘‘I feel I can be useful for at least next 10 years.’’ There were now, he said, 400 million Chinese Buddhists; it was the largest population of Buddhists anywhere in the world. So he was ‘‘very, very keen to return,’’ adding, ‘‘not as the Dalai Lama,’’ but as a ‘‘practitioner of Buddhism.’’

I told him about an invitation I had received to a conference about ‘‘spiritual consciousness’’ in Beijing that had the imprimatur of the Communist Party. He was unexpectedly curious about it. He said that I should have gone, and that if I was invited again I should go and speak frankly to the Chinese: ‘‘You should criticize Dalai Lama institution, like my younger brother.’’

I laughed, but he was again making a point. ‘‘We voluntarily changed that. Why? If there is something good, then no need for change. Because it isoutdated.’’ He added, ‘‘As a Buddhist, we must be realistic.’’

The ‘‘world picture,’’ as he saw it, was bleak. People all over the world were killing in the name of their religions. Even Buddhists in Burma were tormenting Rohingya Muslims. This was why he had turned away from organized religion, engaged with quantum physics and started to emphasize the secular values of compassion. It was no longer feasible, he said, to construct an ethical existence on the basis of traditional religion in multicultural societies.

As he walked onto the veranda, he saw a woman standing there and exclaimed with delight. She was French and visited Dharamsala each year to see His Holiness. The Dalai Lama hugged her and introduced her as a friend he made on his first visit to Europe in 1973. ‘‘Sometimes,’’ he said, ‘‘I describe her as my girlfriend.’’

The Frenchwoman, a sprightly figure at 96, riposted, ‘‘You could get a younger one!’’ Chortling with laughter, the Dalai Lama walked down the veranda, holding her tightly to his waist.

At Glastonbury a few weeks later, the Dalai Lama emerged from a helicopter into a summer drizzle, followed by T.C. Recognizing a monk among the reception party, he clasped his hand and gently bumped his forehead against his, examining his strange new setting with a frank curiosity.

From a vantage point over the large tent-city that sprouts there every summer, he asked the organizers a series of cryptic questions: ‘‘How old?’’ ‘‘When?’’ and — inevitably, since regular bowel movements concern him greatly — ‘‘Toilets?’’ At Green Fields, a 60-acre site dedicated to ‘‘peace, compassion and understanding,’’ he walked through the reverential crowds with a T-shirt draped around his head and started his talk with, ‘‘We are all the same human beings.’’

I sheltered from the rain with T.C. in a Land Rover. T.C. said that Modi had sent a minister to wish the Dalai Lama a happy birthday. But he was still worried. ‘‘Who knows what Modi will do to Tibetans in India?’’ he said. He was also still upset about his elder brother’s book. Gyalo Thondup had traveled to Dharamsala to celebrate the Dalai Lama’s birthday. The brothers met up but had not discussed the book. ‘‘Why write it?’’ T.C. said again.

Out in the rain, the Dalai Lama aimed some lighthearted but sharp-edged remarks at drowsy British flower children. The British, or ‘‘You Britishers!’’ as he called them in his simultaneously blunt and disarming English, had benefited from imperialism and self-interest. Now it was time for them to acknowledge that they lived in an interconnected world.

At lunch — a vegan buffet arranged by Greenpeace — the Dalai Lama saw me and gestured to the bench in front of him. I sat down, acutely aware of the envious and resentful eyes of many people who wanted to eat lunch with the Dalai Lama. He examined my plate. ‘‘You are not having soup? I am having soup first and then more food!’’

A Greenpeace host complained at length about Modi’s government, which was cracking down on Western nongovernmental organizations. The Dalai Lama listened with concern and then said, ‘‘Criticism in India of Modi is growing.’’

At a panel discussion on climate change hosted by The Guardian, he criticized Vladimir Putin’s decision to enhance Russia’s nuclear arsenal and endorsed Pope Francis’ call for moral action. He stressed the importance of personal responsibility. But when the English moderator turned to him and asked, in an earnest, almost pleading voice, ‘‘What should we do?’’ the Dalai Lama replied, ‘‘I don’t know.’’ Earlier, at Green Fields, he was asked about music. He did not think much of it, he said: ‘‘If music really brings inner peace, then this Syria and Iraq — killing each other — there, through some strong music, can they reduce their anger? I don’t think so.’’

While waiting to cut his birthday cake, he watched Patti Smith and her fellow musicians perform. I would read the next day that Smith ended her performance by holding aloft her guitar and shouting: ‘‘Behold, the greatest weapon of my generation!’’ before wrecking her instrument. Given his views on ‘‘strong music,’’ I wondered what the Dalai Lama would have made of this war cry. But by then he was on his way to London. Three days later, he would cut another cake with his friend George W. Bush, with whom he shares a birthday, at the Bush presidential center in Dallas, and announce to the diamonds-and-pearls Republicans, ‘‘I love George Bush, although as far as his policies are concerned I have some reservations.’’

Pankaj Mishra is the author of, most recently, ‘‘From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia.’

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/06/magazine/the-last-dalai-lama.html?smid=fb-share&_r=1