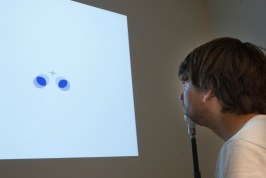

Illusion of colliding objects.

La nostra immaginazione può alterare ciò che vediamo e sentiamo

Mental Imagery Changes Multisensory Perception.

La realtà che ci circonda può essere differente da ciò che percepiamo davvero a causa della nostra immaginazione. Questo può modificare ciò che effettivamente vediamo e udiamo, a riprova che la realtà è più soggettiva, che oggettiva. La nostra immaginazione può influire su quanto vediamo e udiamo: un po’ come dire che il pensiero crea la realtà.

Senza andare troppo in là, affermando che tutto quello che ci circonda, noi compresi, è un’illusione, gli scienziati svedesi hanno dimostrato che la nostra immaginazione influisce su ciò che realmente vediamo e udiamo.

Gli scienziati del prestigioso Karolinska Institutet in Svezia hanno infatti condotto uno studio, pubblicato su Current Biology, in cui si mostra come la nostra immaginazione può influenzare il modo in cui facciamo esperienza del mondo, o della realtà. Spesso è infatti più determinante ciò che immaginiamo di vedere o sentire piuttosto di ciò che realmente c’è o accade – un po’ come dire che la realtà è tutto, o solo, un fattore di testa.

Il cervello dunque dietro alla realtà, che di fatto diviene soggettiva più che oggettiva. Il mondo diviene quello che in qualche modo vogliamo, immaginiamo, piuttosto di quello che è per davvero.

«Spesso pensiamo che le cose che immaginiamo e quelle che percepiamo nella realtà siano chiaramente separabili – spiega l’autore principale dello studio, Christopher Berger, del Dipartimento di Neuroscienze del Karolinska – Tuttavia, questo studio dimostra che immaginare un suono o una forma può cambiare il modo in cui percepiamo il mondo che ci circonda, esattamente come il fatto di sentire realmente quel suono o di vedere davvero quella forma. In particolare, abbiamo osservato che quello che immaginiamo di sentire può cambiare ciò che effettivamente vediamo, e quello che immaginiamo di vedere può cambiare ciò che sentiamo».

Per questo studio i ricercatori hanno coinvolto 96 soggetti sani che sono stati sottoposti a una serie di esperimenti a base illusionistica. Le informazioni sensoriali prodotte in questi test nei confronti di un senso distorcevano la percezione di un altro senso.

Nello specifico, durante il primo esperimento, i partecipanti avevano l’illusione che due oggetti che passavano di fronte a loro andassero in collisione, piuttosto che passare prima uno e poi l’altro, quando hanno immaginato un suono nel momento che i due oggetti si sono incontrati.

Nel secondo esperimento, la percezione spaziale di un suono da parte dei partecipanti è stata deviata verso un luogo preciso in cui hanno immaginato di sentirlo, osservando la breve apparizione di un cerchio bianco. Infine, nel terzo esperimento, la percezione dei partecipanti di ciò che una persona stava dicendo è stata cambiata dal loro immaginare un suono particolare.

Questo studio, secondo gli autori, può aiutare a comprendere come in certe situazioni , come per esempio le malattie mentali, per qualcuno può essere difficile distinguere tra la realtà e ciò che è frutto dell’immaginazione. Tuttavia, in modo più o meno evidente è ciò che facciamo tutti, tutti i giorni quando interpretiamo i pensieri degli altri, quando anticipiamo un evento o facciamo le cose più grandi di quelle che sono – o al contrario minimizziamo. Insomma, a tutto quello che accade intorno a noi diamo sempre la nostra personale interpretazione, spesso mediata appunto dalla nostra immaginazione più o meno fervida e da quelle che sono le nostre esperienze. E’ così che la realtà diviene un’esperienza personale, dove il pensiero crea la realtà. E, forse, quando lo capiremo davvero anche la nostra vita potrà cambiare e diventare come l’abbiamo pensata – questa volta in modo cosciente.

A chiudere, il professor Henrik Ehrsson, sottolinea che «questa è la prima serie di esperimenti a stabilire definitivamente che i segnali sensoriali generati dalla propria immaginazione sono abbastanza forti per cambiare la propria percezione del mondo reale in una modalità sensoriale diversa». Il pensiero, dunque, crea la realtà. http://www.lastampa.it/2013/07/01/scienza/benessere/la-nostra-immaginazione-puo-alterare-cio-che-vediamo-e-sentiamo-NQuVjT1WqYtbsawjzwz7mL/pagina.html ,

http://ki.se/ki/jsp/polopoly.jsp;jsessionid=aLcWyxIvMN9cl0MZad?l=en&d=130&a=165632 ,

Mental Imagery Changes Multisensory Perception

Current Biology, Publication Date 27 June 2013, Volume 23, Issue 14, 22 July 2013, Pages 1367–1372.

Christopher C. Berger, H. Henrik Ehrsson

Department of Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, 17177 Stockholm, Sweden

Summary

Multisensory interactions are the norm in perception, and an abundance of research on the interaction and integration of the senses has demonstrated the importance of combining sensory information from different modalities on our perception of the external world [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. However, although research on mental imagery has revealed a great deal of functional and neuroanatomical overlap between imagery and perception, this line of research has primarily focused on similarities within a particular modality [10,11,12,13,14,15,16] and has yet to address whether imagery is capable of leading to multisensory integration. Here, we devised novel versions of classic multisensory paradigms to systematically examine whether imagery is capable of integrating with perceptual stimuli to induce multisensory illusions. We found that imagining an auditory stimulus at the moment two moving objects met promoted an illusory bounce percept, as in the classic cross-bounce illusion; an imagined visual stimulus led to the translocation of sound toward the imagined stimulus, as in the classic ventriloquist illusion; and auditory imagery of speech stimuli led to a promotion of an illusory speech percept in a modified version of the McGurk illusion. Our findings provide support for perceptually based theories of imagery and suggest that neuronal signals produced by imagined stimuli can integrate with signals generated by real stimuli of a different sensory modality to create robust multisensory percepts. These findings advance our understanding of the relationship between imagery and perception and provide new opportunities for investigating how the brain distinguishes between endogenous and exogenous sensory events.

Highlights

- • We examined whether imagined and real stimuli can lead to multisensory percepts

- • Evidence of imagery-percept multisensory integration in cross-bounce illusion

- • Evidence of imagery-percept multisensory integration in ventriloquism

- • Evidence of imagery-percept multisensory integration in modified McGurk effect

Figure 1. Altered Motion Perception from Imagery(A) Proportion of perceived bounce when no sound was imagined and when sounds were imagined before, at, and after the moment of coincidence. The timing of the imagined sound led to significant alterations in the perception of motion [F(3, 19) = 9.78, p < 0.001]. Planned comparisons revealed a significant promotion of the perception of bouncing when the sound was imagined at the moment of coincidence compared to the passive viewing condition [t(21) = 3.77, p = 0.001], whereas imagination of the sound before [t(21) = 1.31, not significant (n.s.)] or after [t(21) = –0.12, n.s.] coincidence did not. See the Supplemental Results for the results of an additional condition containing tactile imagery (data not shown).(B) Proportion of perceived bounce for both the imagined and real sound at coincidence, finger lift at coincidence, and view-only conditions. Planned comparisons revealed that imagination of a sound at the moment of coincidence significantly promoted the perception of bounce compared to the passive viewing [t(11) = 5.26, p < 0.001] and imagined finger lift [t(11) = 3.35, p = 0.007] conditions, whereas imagination of the finger lift [t(11) = 1.77, n.s.] or a real finger lift [t(11) = .54, n.s.] did not. Error bars represent ± SEM. Asterisks between bars indicate significance (∗∗p < 0.01) for planned comparisons.See also Figure S1.

Figure 2. Ventriloquism Effect from Visual Imagery(A) Percent visual bias for stimuli presented at disparities of 15° and 30° for both imagined (left) and real (right) visual stimuli. Significant biases of perceived sound location toward the imagined visual stimuli were observed for disparities of 15° [t(20) = 4.11, p = 0.001, single-sample t test (test value = 0)] and 30° [t(20) = 18.39, p < 0.001, single-sample t test (test value = 0)], with a stronger bias for disparities of 30° compared to 15° [t(20) = 2.05, p = 0.05, paired-samples t test]. Significant visual biases were also observed for 15° [t(20) = 10.38, p < 0.001, single-sample t test (test value = 0)] and 30° [t(20) = 27.87, p < 0.001, single-sample t test (test value = 0)] disparities, and a stronger bias for disparities of 30° compared to 15° [t(20) = 2.76, p = 0.012, paired-samples t test] was observed in the perceptual version of the experiment.(B) Multisensory enhancement of congruent, 15° incongruent, and 30° incongruent audiovisual stimuli for imagined (left) and real (right) stimuli. Multisensory enhancement of auditory perception was observed when the participant imagined a visual stimulus in the same location as an auditory stimulus [t(20) = −3.63, p = 0.002, single-sample t test (test value = 0)]. Correspondingly, a significant multisensory enhancement of auditory perception was also observed for a real visual stimulus presented in the same location as an auditory stimulus [t(20) = −8.20, p < 0.001].(C) Mean location, in degrees, of the first eight response reversals on each staircase for the imagine-circle and no-circle conditions.(D) The average distance (in degrees) between the left and right staircases was significantly larger in the imagine-circle condition than in the no-circle condition [t(17) = 2.39, p = 029]. Error bars denote ± SEM. Asterisks above bars indicate significance (∗∗p < 0.01) for single-sample tests. Asterisks between bars indicate significance (∗p < 0.05) for paired-sample tests.See also Figures S1 and S2.

Figure 3. Auditory Imagery-Induced McGurk EffectProportion of perceived illusory “da” when the participants imagined hearing “ba,” imagined hearing “ka,” or passively viewed silent videos of a person saying “ga” for McGurk illusion perceivers and nonperceivers. A significant 3 (imagine “ba,” imagine “ka,” view only) × 2 (perceivers, nonperceivers) interaction was observed [F(2, 21) = 5.18, p = 0.01]. A significant increase in the illusory “da” percept was observed in the imagine-“ba” condition for perceivers compared to nonperceivers [t(21) = 2.73, p = 0.012]. No significant differences were observed between perceivers and nonperceivers for the imagine-“ka” [t(21) = −0.93, n.s.] or view-only [t(21) = −0.52, n.s.] conditions. Error bars denote ± SEM. The asterisk indicates significance (∗p < 0.016) for independent sample tests. See also Figure S1.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982213007033 ,

-