The compulsory ecological migration of the Tibetan nomads is grounded in ignorance, prejudice, and a failure to listen and learn.

A Culture Endangered: Depopulating the Grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau

By Tenzin Norbu, Human Rights in China

Overview: Melting Tibetan Plateau

With an average elevation of 4,500 meters, the Tibetan Plateau is one of the most distinctive land-features on earth. It occupies an area of 2.5 million square kilometers—more than one quarter of the size of China—and is the world’s highest and largest plateau in the world. For many generations, this Plateau has provided the basic necessities to sustain life, allowing human civilization to flourish beyond its vast border. The modern era now begins to acknowledge the significance of its strategic location for both developing peace and harmony within the region or conflict.

The Tibetan Plateau, also referred as “The Water Tower of Asia,” is the headwaters of major rivers that flow into India, Bangladesh, China, Nepal, Pakistan, Thailand, Myanmar, and Vietnam. Approximately 1.3 billion people are directly dependent on the health of ten major rivers that originate in Tibet. The total river basin area is estimated to be greater than 5.6 million square kilometers. With its snow peaks and glaciers, the Plateau provides freshwater resource to a wide swatch of Asia, in areas ranging from the deserts of Pakistan and India to the rice paddies of southern Vietnam, from the great Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia to the North China Plain.

In recent years, critical components of Tibet’s ecosystem are undergoing major transformations due to climate change. For instance, climate change has led to receding glaciers, shrinking and disappearance of thousands of lakes, drying of wetlands, thawing of permafrost, and reduced flow regimes in many rivers. Abnormal weather conditions due to climate change have made subsistence farming and herding more unpredictable, thus impacting the livelihoods of a majority of Tibetans. These days, on the Plateau, the spring thawing is earlier and the permafrost is melting away before the growing plants can access the water. These changes affect not only the crops but also the native vegetation of Tibet, especially in wetlands and other low lying areas. The loss of wetland in turn threatens the migratory birds that are used to making Tibetan stopovers during the mating season.

Endangering Pastoralism and Grasslands Stewardship in Tibet

It was mobility that was the very essence of herding. Pastoral nomads in the Old World Dry Belt, whether in the savannahs of Africa, the steppes of central Asia or the high altitude pastures of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, have always needed to move their animals regularly to make use of the spatial and temporal patchiness of grassland resources. Nomadism was therefore more than just an ecological adaptation or an adaptation to the political environment. It was a ‘region-specific, temporally and spatially ubiquitous survival strategy… an alternative to the sedentary cultures of agricultural and urban societies.

Fred Scholz, Nomadismus. Theorie und Wandeleinersozio-ökologischenKulturweise (Nomadism.Theory and change of a socio-ecological mode of culture), 1995.

While often ridiculed as primitive or even ‘incomplete’ by outsiders, [nomadism] is in fact a highly sophisticated adaptation for exploiting energy captured in the grasslands of the region.

R. Merkle, “Nomadism: A socio-ecological mode of culture,” 2000. Centre for Development Studies, Institute of Geographical Sciences, Free University of Berlin, Germany.

Mobility was crucial, moving on before grazing pressure destroys plants, exposing the dying turf to the icy gales and blizzards of Tibet which can strip soil, leaving only bare rock. Nomadic knowledge of how, when and where to graze, and the nomadic willingness to live in portable woven yak hair tents, summer and winter, with their animals, kept the pasture free of invasive toxic weeds, erosion, shrub invasion, and infestations of pests. None of this was known in the 1980s, except to the nomads themselves…. It is only in the 21st century that Chinese and global science have caught up with what the nomads have always known.

Gabriel Lafitte, development policy expert, from communications with the author, 2010.

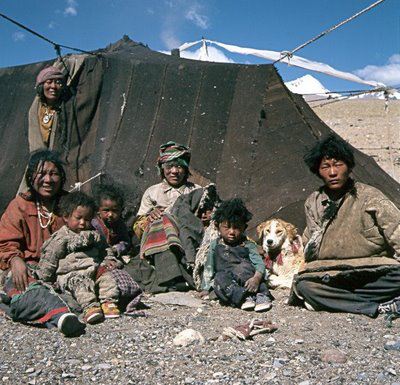

Pastoralism on the Tibetan Plateau is an adaptation to a cold environment at elevations above the limit of cultivation. For centuries, the Tibetan nomads, drogpas, in Tibetan, and herders have successfully maintained a sustainable and mobile lifestyle, traveling from winter to summer pasture lands and from autumn to spring pasture lands (Figures 2 & 3). The grasslands on the Tibetan Plateau represent one of the last remaining agro-pastoral regions in the world. Almost 70 percent of the Plateau itself is covered in these precious grasslands. The pasture lands are made habitable through the co-existence of the Tibetan people and their yaks. Through their efforts, they have maintained sustainable use of this area for many centuries.

China’s grassland policies over the past several decades, however, threaten the sustainability of this delicate environmental balance. The policies have reduced the flexibility and mobility of the nomads, which are the key components of nomadic pastoral production. At the same time, the livestock has been blamed for overgrazing the grasslands.

In the name of modernization and conservation, Chinese authorities forcibly removed the Tibetan nomads from their ancestral pastoral lands and compelled them to slaughter and sell their livestock. The nomads have been made to live on state rations; some of them sold their belongings to become small vendors. And their lack of other skills prevents them from finding alternative means of making a living.

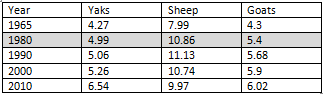

During the era of the commune system, 1958-1979, the nomads were herded into communes, stripped of all their possessions, turned into production brigades, and given rations according to their work points. No production meant no rations. From the outset, the new class of cadres in command saw the nomads not as stewards and curators of the landscape, but as ignorant, backward, and irrational people, utterly lacking in enthusiasm for class struggle. At the same time, under the control of the new cadres, the herd size steadily grew to unsustainable levels and the chain of grassland degradation began. Twenty years later, in the late 1970s, the communes collapsed, having failed except for one achievement: the number of animals, in all Chinese official statistics, had climbed steadily every year.

-

- Table 1. Numbers of grazing animals, in millions, in Tibet Autonomous Region, as reported by Tibet Statistical Yearbook

In the early 1980s, nomads were given their animals back, but not their land. As soon as they regained some control over their lives, the nomads cut the number of sheep back to more sustainable levels. It is now widely known that grassland degradation and the increased grazing pressure actually started with the commune system.

The Household Contract Responsibility System (HCRS) or the “Grassland Law” was adopted in 1985, ostensibly to protect the degrading grasslands and to modernize animal husbandry. But some researchers argue that, in fact, the law was implemented to enable the government to gain more control over the pastures and to stop the over-exploitation of the grasslands, which the government apparently viewed as the most important cause of grassland degradation. In the 1980s Tibetan nomadic herders, like China’s peasant farmers, were officially promised long term land tenure, to encourage them to see their allotted grazing land as theirs, and be motivated to care for it. Long after the Chinese farmers had been given such guarantees of land use in the form of land lease certificates, the nomads were at last given the same guarantees, in the 1990s—long-term leaseholds to their land that ranged from 30 to 50 years. This encouraged conservation of pastures and gave the nomads a sense of ownership.

Along with the Grassland Law, state authorities gradually implemented the so-called Four-Way Program or“Si Pei Tao”(四配套), ordering region-wide fencing regimes and the construction of shelters for nomads and livestock (Fig 4). The Animal Husbandry Bureau, the implementing agency of the program, stated that this program was meant to improve people’s lives and control livestock and grazing. In practice, the program limited the mobility of the livestock and encouraged the herders to invest and spend more time in winter pastures, resulting in increased grazing pressure on a smaller land area. Thus the program in fact intensified, or, at least in part, caused, the problems for which the herders are now being blamed. At the same time, other policies, driven by China’s longstanding disdain for mobile people, were also implemented. Limits on family size and herd size were gradually made compulsory. Gone was the annual cycle of overwintering in lower plateau pastures and herding up into the alpine meadows in summer. Mobility was compromised and curtailed.

In the 1990s, after the implementation of a series of policies and measures, it became obvious that everything on the grasslands was going wrong. The living turf was dying, eroding, and slumping, only to be torn away by wild weather, reduced to bare rock or “black beach,” as Chinese scientists called it. Burrowing rodent populations exploded, in plague proportions. Toxic invasive weeds multiplied. The rangelands were degrading, including the arid area of northeastern Tibet where both of China’s great rivers, the Yangtze and Yellow River, rise from glacier melt.

Chinese scientists and administrators offered only one explanation: the nomads were overstocking beyond the carrying capacity of the pastures. The compulsory overstocking during the commune system was not mentioned; the subject was, and still is, off-limits. But recent research has revealed that overgrazing and degradation of the grasslands are not the result of grazing livestock alone. Herders point to weather changes, rodents, and mining activities as important factors causing grassland changes.

In 2003, a grassland rehabilitation policy was implemented throughout China’s grasslands and in pastoral areas. In Chinese, the Restore Grassland Policy is called tuimu huanco(退牧还草), which means “closing pastures to restore grasslands.” The key measure of this policy is the relocation of herders from the grasslands to state-built housing, a measure that has been intensified in recent years. The land lease certificates guaranteeing nomads long term land tenure have been nullified. Instantly, all of the herders’ skills, risk management strategies, environmental services, traditional knowledge, and biodiversity conservation practices were made superfluous. The harshest measures have been enforced in Golok and Yushu prefectures, in the area China considers to be the source of its great rivers. There, in Chinese view, the downstream water supply is threatened by rangeland degradation caused by destructive nomads. In this large area, nomads are frequently “villagized” in new concrete settlements called “line villages” that are far from their customary grazing land, and they are required to sell their livestock.

For decades, other policies such as de-stocking and rodent poisoning were enforced against the religious sentiments of the herders. For instance, one person from each family is required to join in the drive to poison the rodents, the Tibetan pikas. Tibetans find it deeply distressing to have to poison the animals whose habitat they share. They also dislike having to sell so many animals, both because raising animals for slaughter is against Buddhist ethics, but also because, in a land with no social safety net, herd size is the only wealth, security, insurance, capital, collateral against loans, and dowry. Over the past 40 years, the Chinese government has sponsored the systematic poisoning of pikas, most recently using grain laced with Botulin C strain toxin (Clostridium botulinum). Approximately 320,000 square kilometers grasslands were poisoned! But researchers have argued that these rodents are the keystone species of the grasslands, and that their large-scale killing may even be harmful for the grasslands and is almost certain to affect other wildlife and the broader environment.

China’s own scientists have now learned, through patient observation that the grasslands of Tibet, when grazed moderately and intermittently, with herds being moved on well before the short summer growing season ends, actually maintain a higher biodiversity than un-grazed pastures, where toxic weeds pervade and biodiversity declines.

What Science Says about Grassland Degradation

Many researchers have found that depopulating these grasslands and labeling the nomads as ecological migrants will not help to restore the pastures. Although the stated objective of tuimu huancao is to grow grass and thus conserve watersheds, careful scientific observation shows that when all grazing is removed, the biodiversity of grasses diminishes, medicinal herbs are driven out by toxic weeds, and woody shrubs make the land unusable.

Research has shown that the carrying capacity of some grasslands has been far exceeded partly due to the inappropriate land-use and land management practices of the 1950s. Researchers also cite rainfall—rather than livestock numbers, past or present—as the major determinant of grassland productivity on the Tibetan Plateau. Some recent field studies also revealed that grazing actually helps regenerate the grasslands by improving the soil carbon-nitrogen ratio and extending the growing season. Even some Chinese researchers have attributed the degradation of these grasslands to factors such as permafrost degradation, irrational human disturbance (mining, road construction, conversion of grassland to cropland, gold mining, overgrazing etc.), and climate warming.

Field observations conducted on these grasslands indicate positive connections between the grazing herds of the nomads and the grasslands. Researchers say that abandoning these grasslands will lead to the domination by invasive species and reduced biodiversity. Damage to the grasslands would in turn affect the permafrost soil.

Status Quo

Joblessness and alcoholism amongst the youth are prevalent in the new settlements—where the elders are often seen reminiscing their past lives and reliving them in their memories, and the younger ones are scavenging to earn a little extra money. From our recent interactions with drogpas and herders who fled into exile in India, and from research conducted inside Tibet, we came to know that the current policy of forced “villagization” is in fact a very strategic move on the part of the state to keep all the mobile pastoral wanderers on a tight leash and to have open access to pastures for extractive industries without facing any resentment. The policy also enables the central government to boast that it has made sizable investments in elevating the lifestyles of local residents. But, as many anthropologist and scholars recognize, development has less to do with external materialistic life than with the freedom to choose and to lead the life that one values and respects. Given the choice of livelihood, we believe that almost all the residents of these newly constructed concrete settlements would prefer to go back to their previous lifestyle without a second thought, even it if meant leaving a two-bedroom house.

A documentary, “The Last Of The Mogru Nomadic Clan,” has captured the plight of the displaced drogpas in Mogru, in Qinghai. Chinese tourists who visit Mogru town like to be photographed with Tibetan children of the Mogru clan, who are made to dress as if they are timeless nomads, people without history, forever smiling. Perhaps the tourists do not know that the land of the clan was taken to build the Atomic City tourist facilities, and the Mogru Tibetans have no source of income other than posing for happy tourist snapshots. Attempts by the Mogru Tibetans to petition Beijing and seek justice have come to nothing.

We have found that the people being moved or lured to these concrete settlements under the guise of different programs euphemistically named ecological migration or comfortable housings projects number approximately 3.2 million in whole of Tibet, including Amdo and Kham province. According to Chinese state media in 2011, another 185,500 families are expected to move into new homes by 2013. These figures reflect the number of people whose lifestyle is now directly under the control of the central government and nothing more.

Following his mission to China in December 2010 where he saw the conditions of the newly-settled drogpas and herders in the concrete camps, Prof. Olivier De Schutter, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, publicly opposed the resettlement policy.[1] More recently, on March 6, 2012, at the UN Human Right Council in Geneva, he again expressed concerns about the displaced people living in the “new socialist-villages”.[2]

Conclusion

The compulsory ecological migration of the Tibetan nomads is grounded in ignorance, prejudice, and a failure to listen and learn. China is far from alone in assuming its nomads are backward and responsible for degrading land. But around the world, governments now increasingly recognize that pastoral nomadic mobility holds the key to sustainability on the dry lands of the world.

Any development in Tibet should be based on the approach of listening to the land and listening to the people. The land and its resources must be used within its capabilities and ecological limits; and any policy implementation and developmental activities must respect the cultural tradition of Tibetans, which is based on centuries-old practice of sustainable use.

The experiences and intimate knowledge of pastoral nomads should be incorporated into rangeland management practices. There should be a principle of collaborative management attending to the needs of the pastoral nomads and herders alike.

A healthy and sustainable Tibetan Plateau is important because it would benefit the entire Asian continent and would further enhance peace and harmony within the region, especially between two major super powers, India and China.

Tenzin Norbu is the Director of the Environment and Development Desk of the Central Tibetan Administration in Dharamsala, India. He is a graduate of the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) in Thailand, where he studied Environmental Technology and Management, and later worked as a senior researcher in the Environmental Engineering Program. He was born in India.

Notes

[1] UN – A/HRC/19/59/Add.1 Human Right Council 19 Session, Agenda item 3.

[2] UN Special Rapporteur challenges China’s forced resettlement policy in Tibet, http://tibet.net/2012/03/07/un-special-rapporteur-challenges-chinas-forced-resettlement-policy-in-tibet/

References

Anthony D. Arthura, Roger P. Pecha, Chris Daveya, Jiebub, Zhang Yanmingc, Lin Huid, Livestock grazing, plateau pikas and the conservation of avian biodiversity on the Tibetan plateau, Biological Conservation 141 (2008) 1972 -1981

Associated Press, phayul.com, China forcing Tibetan nomads to settle in towns, http://www.phayul.com/news/article.aspx?id=16790&t=1

Barnett, T.P., Adam, J.C., Lettenmaier, D.P., 2005. Potential impacts of a warming climate on water availability in snow-dominated regions. Nature 438, 303–309.

Breivik, Irene. 2007. THE POLITICAL ECOLOGY OF GRASSLAND CONSERVATION IN QINGHAI PROVINCE, CHINA: DISCOURSE, POLICIES AND THE HERDERS. MA thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences , Department of International Environment and Development Studies, NORAGRIC http://www.case.edu/affil/tibet/tibetanNomads/documents/IreneBreivikpoliticsgrasslands.pdf

D.J. Miller, ‘Why Tibet Matters Now Part 1′, China Dialogue, http://www.chinadialogue.net

EDD-COP15 Briefing papers, Environment and Development Desk, DIIR, Central Tibetan Administration, Dharamsala, HP, India. Available online,http://tibet.net/publications/

Environment and Development Desk, ‘TIBET, A Human Development and Environment Report’ EDD, DIIR, Central Tibetan Administration, Dharamsala, HP, India, ISBN 81-86627-68-5, (2008).

Gabriel Laffite, personal communication. www.rukor.org (2010).

Guodong Cheng and Tonghua Wu, Responses of permafrost to climate change and their environmental significance, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Journal of Geophysical Research, Vol. 112, 2007 http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2007-07/17/content_5437231.htm

Human Rights Watch, China “No One Has the Liberty to Refuse”, Tibetan Herders Forcibly Relocated in Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region, June 2007, Volume 19, No. 8 (C).

J. Marc Foggin, Depopulating the Tibetan Grasslands, National Policies and Perspectives for the Future of Tibetan Herders in Qinghai Province, China, Mountain Research and Development Vol 28 No 1 Feb 2008: 26–31, doi:10.1659/mrd.0972. http://www.case.edu/affil/tibet/tibetanNomads/documents/Foggin_J._Marc.pdf

Jane Q., China: The third pole: Climate change is coming fast and furious to the Tibetan plateau, naturenews, Published online July 23, (2008).

John Isom, Tibet’s Nomadic Pastoralists: Tradition, Transformation and Prospects, http://www.iwgia.org/publications/search-pubs?publication_id=402

Julia A. Klein, John Harte and Xin-Quan Zhao, Experimental warming causes large and rapid species loss, dampened by simulated grazing, on the Tibetan Plateau, Ecology Letter, (2004).

Julia A. Klein, John Harte and Xin-Quan Zhao, Experimental warming, not grazing, decreases rangeland quality on the Tibetan Plateau, Ecological Applications, 17-2, (2007).

Matt Perrement, ‘Resettled Tibetans “can’t live on charity forever”, China Development Brief, Reporting the latest news on China’s social development. http://www.surmang.org/pdf/pah1.pdf

PhurbuThinley,phayul.com,,China relocates 6000 Tibetan nomads in Shangri-la under its controversial program, http://www.phayul.com/news/article.aspx?id=28631&t=1

Ptackova: Sedentarisation of Tibetan nomads in China: Implementation of the Nomadic settlement project in the Tibetan Amdo area; Qinghai and Sichuan Provinces. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice 2011 1:4.

R. Merkle, Nomadism: A socio-ecological mode of culture, Centre for Development Studies, Institute of Geographical Sciences, Free University of Berlin, Germany.

http://www.ilri.org/InfoServ/Webpub/fulldocs/yakpro/SessionA12.htm

Scholz F. 1995. Nomadismus. Theorie und Wandeleinersozio-ökologischenKulturweise (Nomadism. Theory and change of a socio-ecological mode of culture). Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany. 300 pp.

Tenzin Norbu and Chokyi „Climate Change on the Roof of the World‟, Global Convention on Climate Security and Eco – Investors Forum, S M Convention Centre, Palampur (HP), India.12 – 14 June 2009, pp. 123- 124

Tony Lovell and Bruce Ward, Regenerating grasslands (2009), http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2009/jul/13/manchester-report-grasslands