His Holiness the Dalai Lama: “I’ve been thinking about these things for a long time, emptiness for 60 years and bodhichitta for about 50 years. Understanding them takes time, but you have to keep up your analysis. It is possible to reduce the afflictive emotions. It’s not easy, but if you make the effort you can gradually bring about change, which will give rise to peace of mind.

“We all have the seed of Buddhahood within us. The emptiness of the mind of the Buddha and the mind of sentient beings is the same.”

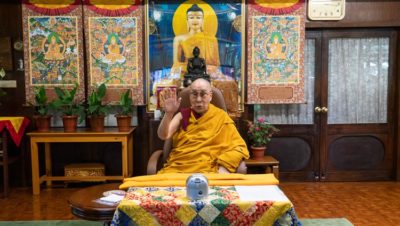

July 17, 2020. Thekchen Chöling, Dharamsala, HP, India – When His Holiness the Dalai Lama entered the room this morning, he scrutinized the faces on the screens before him, recognised several of them, waved to them, laughed and took his seat.

This morning’s moderator, Suresh Jindal, wished His Holiness good morning on behalf of the Indian Sangha. He also thanked him for accepting their request to teach.

“In spite of my age, my being 85 years old,” His Holiness began, “there’s nothing wrong with my physical condition. This is mainly because my mind is at peace. I have no anxiety and I’m inspired by verses by Shantideva:

And now as long as space endures,

As long as there are beings to be found,

May I continue likewise to remain

To drive away the sorrows of the world.

Just like the earth and space itself

And all the other mighty elements,

For boundless multitudes of beings

May I always be the ground of life, the source of varied sustenance.

“In order to be of service to others, not only on a physical level, but also on the level of mental peace, I am determined to live another 15 or 20 years.“Today, you’ve asked me to explain ‘Entering into the Middle Way” https://www.sangye.it/altro/?p=3263. I received an explanation of this from Ling Rinpoché, my Abbot, the one who gave me the bhikshu vow. I memorized this work along with ‘Ornament for Clear Realization’, starting when I was about seven years old and had little interest in it. Gradually, however, I came to find that this text, as with so many others by Nalanda Masters, is very useful. When we encounter difficulties, what we read here gives us courage and self-confidence.

“I want to let you know why this text is important. Soon after his enlightenment Buddha Shakyamuni taught the Four Noble Truths, the basis of the Buddhadharma. Since no sentient being with feelings wants to encounter suffering, he taught about suffering first. Then he explained its origin. Next, he revealed the third truth, that there is cessation of suffering, which entails the complete elimination of its causes. Finally, the fourth truth concerned the path.

“What is important is to analyse cessation, to investigate the cessation of destructive emotions that are the cause of suffering. We have to ask if we can eliminate these mental afflictions. In briefly mentioning the possibility of cessation, the Buddha referred to the 37 factors of enlightenment, first among which are the four foundations of mindfulness. These comprise mindfulness of the body, feelings, the mind and the dharma.

“Usually we are distracted by our sensory experiences, but these are actually dependent on our mental consciousness, something of which we are often unaware. So, we need to develop a mindfulness of mind. This entails ignoring the five sense consciousnesses and paying attention to the mind alone. We need to practise meditation and, determined to focus only on the mind, to get a feeling for it. At first it seems like something empty, but later clarity emerges. To start with we’ll be able to focus on it for just a few seconds, then a few minutes and so on. With time we acquire deeper experience.

“One aspect of the nature of the mind is its clarity. It is this that enables us to develop concentration, a calmly abiding mind, that can in turn be applied to analysis and the generation of insight. Just as scientists analyse matter, by employing mental inquiry we can analyse the mind. This is a real method to change our minds. We need both single-pointed concentration and analysis.”

His Holiness remarked that those who follow the Pali tradition do not do much analysis or philosophical thinking. They have faith in the Buddha’s words and follow them. Those who follow the Nalanda Tradition, however, take a logical approach. They follow the Buddha’s advice to his disciples to be sceptical: ‘”As the wise test gold by burning, cutting and rubbing it, so, bhikshus, should you accept my words — only after testing them, and not merely out of respect for me.”

His Holiness declared that Nalanda Masters like Nagarjuna were not only good monks, they were also great scholars. They used logic extensively. They were determined that if they found a contradiction in something the Buddha had said, they could reject it. Consequently, they divided the scriptures into those that are definitive and those in need of interpretation.

“Nagarjuna https://www.sangye.it/altro/?cat=99 was like a second Buddha,” His Holiness continued. “His principal work was the ‘Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way’ https://www.sangye.it/altro/?p=513 a wonderful book that I read regularly. His main disciple was Aryadeva https://www.sangye.it/altro/?p=10173 who wrote the ‘400 Verses’ https://www.sangye.it/altro/?cat=72. In ‘Fundamental Wisdom’ Nagarjuna states:

Through the elimination of karma and afflictive emotions there is liberation.

Karma and afflictive emotions come from conceptual thoughts.

These come from mental fabrication.

Fabrication ceases through emptiness.

“We spin in the cycle of existence because of negative karma, negative action, and liberation can only be attained by eliminating by karma and afflictive emotions. Mental afflictions are rooted in the ignorance that believes that things exist as they appear. Nagarjuna writes that mental afflictions arise from conceptual thoughts that arise from exaggerated fabrication. Such wrong views can only be eliminated by understanding reality, not through prayer or faith. When quantum physics says that things appear to exist objectively, but that the observer contributes to this, it corresponds to Nagarjuna’s thought.

“One of Aryadeva’s verses refers to this too.

As the tactile sense [pervades] the body

Confusion is present in all [afflictive emotions].

By overcoming confusion, you will also

Overcome all afflictive emotions.

“By destroying ignorance and confusion, all mental afflictions can be eliminated. The root of the problem is having misconceptions about the true existence of phenomena and self. Aryadeva further points out:

When dependent arising is seen

Confusion will not occur.

Thus, every effort has been made here

To explain precisely this subject.

“Since suffering is rooted in ignorance, we must cultivate the wisdom understanding selflessness that is not merely a philosophical idea, but a source of practical relief. When you can see that things do not exist as they appear, afflictive emotions will also cease. This is why Aryadeva declares that dependent arising should be taught from the outset.

“This text, ‘Entering into the Middle Way’ and its auto-commentary are important because they summarize ‘Fundamental Wisdom’ the ‘400 Verses’, ‘Buddhapalita’ and so forth. Nagarjuna had many followers, but the one who explained his thought most precisely was Chandrakirti.”

His Holiness pointed out that followers of the Autonomist Middle Way (Svatantrika Madhyamaka) propound a form of objective existence. They say the object of negation is things having a unique mode of existence from their own side not reliant on valid cognition.

If the intrinsic characteristics of things were to arise dependently,

things would come to be destroyed by denying it;

emptiness would then be a cause for the destruction of things.

But this is illogical, so no real entities exist.

Chandrakirti goes on (6.34- 6.38) to explain that things having objective existence would entail four logical fallacies: the Arya being’s meditative absorption on emptiness would be the destroyer of phenomena; it would be wrong to teach that things lack ultimate existence; the conventional existence of things would be able to withstand ultimate analysis into the nature of things, and it would be untenable to state that things are empty in and of themselves.

When we analyse an object, dividing it up into ever smaller parts, the object cannot be found. So, it is with consciousness which we think of as a continuum. The past is gone, the future is yet to come and the present cannot be pinpointed. Chandrakirti illustrates how things cannot be found with the sevenfold analysis of a chariot.

A chariot cannot be said to be different from its parts;

it is not identical with the parts, nor does it possess the parts;

it is not in the parts, nor do the parts exist in it;

it is not the mere collection, nor is it the shape.

For if the mere collection constitutes the chariot,

the chariot would exist even when the parts are not assembled;

since there can be no parts without the bearer of the parts,

that shape alone is the chariot is illogical as well.

Things can’t be found in terms of the sevenfold analysis, but they do exist by way of convention. Consequentialists (Prasangikas) say things have no ultimate existence, but do exist by way of designation.

“When we say things do not exist as they appear,” His Holiness went on, “they do exist by way of dependence on other factors. They give rise to effects. Choné Lama Rinpoché said, “Dependence does not deny suchness; arising does not deny worldly convention.” The Buddha taught dependent arising and the two truths. Things appear to exist, which is conventional reality. Ultimate reality is how they exist.

“When the Buddha taught the four noble truths, he first explained their nature, then their function. But ultimately, he explained that although suffering must be understood, there’s nothing to be understood. Although the origin of suffering is to be eliminated, there is nothing to be eliminated, and so forth, which reveals the two truths. Similarly, although cessation is to be attained, there is nothing to attain and although the path is to be cultivated, there is nothing to be cultivated.

“True cessation is taught more thoroughly as part of the perfection of wisdom. The ‘Heart Sutra’ refers to the fourfold expression of emptiness:

Form is empty; emptiness is form. Emptiness is not other than form; form also is not other than emptiness.

“The Buddhas of the three times become enlightened on the basis of realizing emptiness.”

His Holiness noted that the Buddha taught the four noble truths in his first round of teachings and revealed that there is true cessation. In the second round he revealed that all phenomena lack intrinsic existence. In the final, third round, which included the ‘Unravelling of Thought Sutra’, the distinction is drawn between self-characterized phenomena and imputed phenomena, which have no self-defined characteristics.

His Holiness then turned to the verses of ‘Entering into the Middle Way’, which begin by noting that the main cause of Buddhahood is compassion, holding others dearer than yourself. The awakening mind of bodhichitta has its root in compassion. Thus, compassion is praised right from the start.

He observed that the seven billion people living on this earth are sustained by love and affection. Everyone needs compassion, which is the root of happiness. There is much talk about world peace, but it must come from individuals developing inner peace. And the source of that is compassion.

Afflictive emotions arise on the basis of misconceptions of true existence. Chandrakirti makes the point in his auto-commentary that without insight into the selflessness of phenomena it is not possible to fully understand the selflessness of persons.

His Holiness disclosed that 50 years ago he was reading Jé Tsongkhapa’s commentary to ‘Entering into the Middle Way’, ‘Illumination of the Thought’ and when he read that a person is neither one with the psycho-physical aggregates, nor separate from them, but exists in name only, he felt as if he’d been struck by lightning. Subsequently he was able to see that self and others are like illusions, but later realized that he had had an insight into a coarse form of selflessness. Nagarjuna refers to this selflessness in his ‘Precious Garland’:

A person is not earth, not water,

Not fire, not wind, not space,

Not consciousness, and not all of them.

What else is a person other than these?

After this His Holiness answered several questions from the virtual audience. To distinguish between the needs of compassion for self and compassion for others he recommended cultivating an understanding based on listening. Analyse and reflect on what you’ve understood and meditate on the resulting conviction. To gain experience requires merit and wisdom and that will bring about transformation. When you have a compassionate mind, you’ll be of help to both self and others. This, His Holiness remarked, is his own experience.

He told a young woman in Ladakh that a compassionate mind is dedicated to benefiting others. The mind of compassion focusses on sentient beings. The mind of wisdom aims for enlightenment. We need compassion and wisdom.

A young man in Srinagar wanted to know if aspects of wisdom and skilful means can be taught in the context of the two truths without touching on religious sentiment. His Holiness replied that when we talk about the two truths, what appears to us is conventional truth, but looking more deeply into reality reveals ultimate truth. If we have a warm heart intent on helping others, we also need intelligence. We need to see that it is possible to free others from suffering.

“Today, because of the pandemic,” His Holiness observed, “many people are suffering. We need to have compassion combined with an understanding that the threat of the pandemic can be overcome by taking precautionary measures.”

A student at the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics noted that the mind analysing the ultimate nature of the person negates an objectively existent person. But, he asked, why does it also not negate the person? His Holiness referred to a verse in the text,

The parts, qualities, attachment, defining characteristics, fuel and so on,

the whole, quality-bearer, object of attachment, the characterized, fire and so on,

none of these exist when subjected to the sevenfold chariot analysis.

Yet they exist in another way, through everyday conventions of the world.

On the one hand, he clarified, under analysis nothing can be found, and yet things still exist by way of worldly convention. He cited Dromtönpa’s observation that under analysis neither fire nor your hand can be found, but if you put your hand in the fire it’ll get burned.

A professor in Delhi asked how you know the object of negation of selflessness of person is correct. His Holiness referred to his own experience that his self was not separate from the aggregates, but was able to negate a substantially existent self. He recalled that Nagarjuna states that as long as you have a misconception about the aggregates, you will still have a misconception about the self. To realize that the self has no intrinsic existence it’s necessary to see that the aggregates have no intrinsic existence. The self is just a designation.

As the session came to an end, Suresh Jindal offered His Holiness thanks on behalf of all who had attended.

“I’ve been thinking about these things for a long time,” His Holiness told them, “emptiness for 60 years and bodhichitta for about 50 years. Understanding them takes time, but you have to keep up your analysis. It is possible to reduce the afflictive emotions. It’s not easy, but if you make the effort you can gradually bring about change, which will give rise to peace of mind.

“We all have the seed of Buddhahood within us. The emptiness of the mind of the Buddha and the mind of sentient beings is the same.

“See you again.”

https://www.dalailama.com/news/2020/teachings-for-the-nalanda-shiksha-first-day, https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=601034497485606&ref=watch_permalink