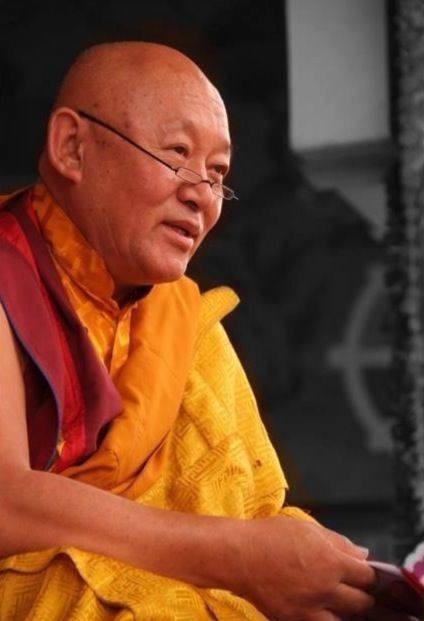

His Holiness The Drikung Kyabgön, Chetsang Rinpoche: All phenomena of samsara and nirvana have one taste, one reality.

His Holiness The Drikung Kyabgön, Chetsang Rinpoche: Dharma Lord Gampopa’s advice.

Notes and questions by Dr. Luciano Villa and Eng. Alessandro Tenzin Villa within the project “Free Dharma Teachings” for the benefit of all sentient beings.

Question: How to deal with the various problems that arise in the practice of Mahamudra meditation?

His Holiness The Drikung Kyabgön, Chetsang Rinpoche

We will now look at Lord Gampopa’s advice on how to deal with the various problems that arise in the practice of Mahamudra meditation. First, in order to avoid errors, one must have a fully qualified lama—that is, a teacher who has actually experienced the realization of Mahamudra. The teacher should not be one in name only but should be someone who has accomplished this path, has knowledge and experience, and who is thereby able to lead others. The student should be one who maintains awareness of the truth of impermanence and death and, motivated by that, exerts him or herself in this practice. He should be able to recognize the fully qualified teacher as being a manifestation of the Buddha himself in the world. So, for the practice to succeed or for the actual practice to even begin, there must be the coming together of a qualified teacher and a qualified student.

When looking for a fully qualified teacher, we don’t need to think in terms of the great enlightened beings of the past such as Dharma Lord Gampopa other, these ultimately accomplished and realized beings. Rather, it is sufficient to have a teacher who has experience in and realization of Mahamudra, though that teacher may be far short of the supreme attainment of the great teachers. Still, if the teacher has a genuine practice of Mahamudra or a true realization of Mahamudra, then that is sufficient to qualify that teacher to transmit the instruction and guide the practice of the disciple.

The disciple, in turn, must be qualified not only by the understanding of impermanence and death, but, beyond that, by having a true appreciation of cause and effect. That is to say he or she must not be one who is negligent of the principle of moral causation, but keeps that in mind. Also, the disciple should be one who has purified his or her defilements and amassed some merit in the lifetimes leading up to meeting the qualified teacher.

Once this coming together of student and teacher occurs, then the path must be traversed correctly. That is, one must go straight along the path and not fall off to one side or the other. Falling off the path, straying from the correct path of meditation leading to the Mahamudra, is described here principally in four ways:

(1) The first error is to mistake a facsimile or a representation of reality for actual reality.

”Reality” refers to reality in its ultimate sense; it means Mahamudra, or emptiness. Here, one falls from the path by relying on a mere intellectual understanding of reality no matter how good the understanding is, instead of actually experiencing it. This can be compared to someone who wishes to go to Bodhgaya and asks someone what it is like. The other person has been there and can describe it in detail all about the road leading up to Bodhgaya, where it turns and where there is a line of trees and where there are temples and where the great stupa is. Even if the second person describes it with great care and detail, the one who has not been there but wishes to go can, at best, only create a mental picture of what it is like. That mental picture will be something of his own devising and will never be the actual thing. If, rather than going there and seeing for himself, he is content with that facsimile, that made-up image in his own mind, then he will fall from the path. So, the person who wants to really see Bodhgaya must go there personally; he cannot be satisfied with the accounts of others.

Likewise, the person who wishes to realize Mahamudra, and with it gain freedom from all limitations and defilements and the attainment of all good qualities, must actually traverse the path and experience it herself with her own mind and not rely on the accounts of others. If one just learns to say that the ultimate nature is without arising, without abiding, and without ceasing and goes no further, one will have nothing much to show for one’s effort. However, if one meditates properly following the advice and precepts of a qualified teacher, one will attain direct insight and then be able to look back on those verses and understand their truth directly. Lord ]igten Sumgon said that it is absolutely indispensable for progress on this path and the attainment of its goal to rely properly upon a qualified spiritual teacher in the beginning, in the middle, and at the end.

(2) The second way of falling from the path is to believe that the attainment of full realization of Mahamudra, the ultimate attainment of perfect Buddhahood, means to leave everything behind and change into something else, to stop being a living person and become a Buddha, as if that were something entirely different. This is a great error which causes one to fall from the path by trying to transform oneself into something that one is not.

The example here is of a child who is born the son of a king. That child might think that when he finally grows up and ascends the throne, he will be something entirely different, and that of course is an error. Just as the prince is a human being, so the king is a human being. There is no sudden transformation into something that one is not. Likewise, the mind of an ordinary human being is not disposed of or left behind. Upon attaining Buddhahood, one does not adopt a new mind or become something totally other than what one was. By thinking this way one loses sight of the path and falls off.

The verse says that becoming a Buddha is to become completely what one already is. To fully manifest the nature of mind is to become fully enlightened; it is not a case of gaining something that does not exist now. Even the highest state of perfect Buddhahood is not other than the nature of one’s mind as it presently is.

(3) The next error which causes one to stray from this path of meditation is to believe that the conceptual mental processes, the kalpana, are something which have to be completely rejected and the pure mind something to be sought separately from those kalpana. This is a subtle error which misunderstands the relationship between the conceptual and dualistic thoughts of mind and mind itself. One thinks that they are something wholly other than mind and, so, tries to grasp a mind that is totally separate or divorced from them, when in fact they are of the same nature as mind.

The example given here is of a plant or tree with great medicinal properties. The medicinal properties of the tree pervade its entirety from its root through its trunk to its branches and leaves. Mistakenly thinking that the medicinal properties are found only in one part, one could inadvertently discard some of the best parts of the tree. So the conceptual processes of mind are not other than mind. Their nature is of mind itself. By trying to exclude them, to cut them off without recognizing their nature and their source, one will never be able to realize mind as it actually is.

(4) Just as mind and its contents should not be separated or thought of as being of different natures, so appearances and emptiness should not be distinguished in that way. This is the fourth way people fall from the correct path: by seeking an emptiness that is an ultimate reality apart from appearances. Thinking that appearances exist in their own right and that emptiness is something to be found elsewhere, they go in search of this emptiness excluding all appearances. This is completely wrong. Appearances themselves are emptiness, emptiness is not apart from them. It says in the Prajnaparamita, ”Form is emptiness and emptiness itself is form; form is no other than emptiness nor is emptiness other than form.” The same is true with all the constituents of existence other than form, such as sensations, concepts, compositional factors in consciousness, or mind itself. All of these things are emptiness.

Emptiness appears as these things and to seek emptiness elsewhere is to make a great mistake and fall off the correct path.

While practising Mahamudra correctly and proceeding along the path, one encounters different levels of realization.

It is very important not to become attached to any of those levels and mistake them as being the ultimate level of realization. lf one does that, then one will certainly get stuck in one of the form or formless realms. So as one’s meditation improves, as one gets higher and higher, one comes to stages which are like vast emptiness where one’s perception, whether one’s eyes are open or closed, is only of vast emptiness and peace. An experience like that could be mistaken for the realization of Mahamudra. lf this occurs, and one thinks it is the ultimate goal and finds satisfaction, this causes rebirth in the form realm.

Likewise, as obstacles are cleared away in Mahamudra meditation, one attains a state of great peace and happiness, characterized by a very high and pure level of bliss. One can become attached to experiencing that bliss. If one becomes attached to it and holds onto that attachment, then at the time of death, one will be reborn in one of the heavens of the desire realm.

If one practices the meditation on Mahamudra and goes beyond these stages of great bliss, one will come to a stage of emptiness. If one does not become attached to that, one will go on to a state of absolute purity where there is nothing whatsoever. One has then gone beyond all appearances, all things which could be called existent or non-existent. This is said to be the state of complete nothingness. This state seems so pure and absolutely free, one can become attached to it.

If one dies clinging to that state, one will be reborn in one of the levels of the formless realm. Because of this, then, it is vitally important as one proceeds in the practice not to become attached to anything, not to any appearance, feeling, sensation, or perception.

Now; avoiding these four ways in which one falls from the path and the three ways in which one gets caught being reborn into the heavenly realms, if one proceeds on the path of Mahamudra without error, then there are three different results depending upon the quality of one’s exertion and practice:

(1) The very highest quality results in one’s attaining in that very life, on that very seat of meditation, the state of perfect, peerless enlightenment equal to that of the Buddhas of the past, present, and future, beyond which there is nothing greater nor any enlightenment more complete. This highest state of perfect enlightenment is said to be like the sun rising up in the empty sky free of all clouds, crystal clear. The sun rises and shines with all of its brilliance, this is the highest level of attainment in this path of Mahamudra.

(2) The middle level of attainment is compared to the sun arising in a sky that has clouds in it. Sometimes the brilliance of the sun will be seen in all its glory then a moment later it will be obscured or there will be some shading of the sun. Then later it will come out again only to be obscured once again. This is the middle level, where one has a realization of ultimate reality but it does not last. There is some hesitation and doubt, and one loses the realization. Practising some more, it comes back for awhile only to be lost again. When one is at this level in the practice, it is of great importance to rely on the qualified spiritual teacher to lead one beyond these final obstacles.

(3) The third, or lowest, type of realization attained through the proper practice of the path of Mahamudra is said to be like the sun shining in a deep canyon. One is down in a deep canyon where it is dark and suddenly the surf shines, but then it’s gone and doesn’t come back. One gets a glimpse of it but cannot see it again. If this is the case, one has to rely on the spiritual teacher. The fault here is really in the relationship between meditation and realization. There was a realization at this point, but the meditation was not sufficient. Meditation really means becoming accustomed to or becoming practised in something. So, one has to become accustomed to that realization so that it is not just a brief flash of insight. Rather, that flash is stabilized and internalized so that it remains and becomes unshakable. It does not disappear in clouds of doubt nor is it obscured by walls of delusion. This requires great exertion in the meditation to extend the realization and make it firm.

These three levels are also distinguished by the practitioners: those with the best practice, the sharpest faculties, and greatest diligence; those with the middle level of faculties and diligence; and those with the lower level. These three types of practitioners will gain these three types of results. It is not enough to have mere intellectual understanding; personal experience of these practices is essential. With the support of shamatha and other means of investigation, we must practice the nature of mind. Then as we progress, different experiences will arise. This yogic, or experiential, path is distinguished by way of four levels of practice:

(1) The first level of practice is called the “one-pointed yoga.” Through one-pointed yoga, one arrives at a certain insight into the nature of mind, you could say the clear light of mind. However, because the focus is so narrow, a question arises subsequently in one’s mind. That question is whether this was an experience or a conceptual realization. In other words, did one actually see it, or did one think one saw it? Did one convince oneself that this was true? So, whether it was conceptual or a directly perceived realization, is in doubt at this point.

(2) The second level of realization is called the “yoga which is free from projection.” This means that one has arrived at the stage of perceiving one’s own mind in terms of its lack of production, abiding, and cessation. One realizes that the nature of mind is free of these three extremes.

(3) The third level is called the “yoga of one taste.” This means that one is able to perceive all phenomena, internal and external, subject and object, as being of one taste, just like sugar is of one taste. No matter what different types of objects sugar is formed into, they all taste sweet. They all have that same taste because they are all of the same essential nature. Likewise, subject and object, inner and outer, all phenomena, whether mind itself or mind’s objects, are of one taste.

(4) The final stage of yogic meditation is called “that which is free of meditation and non-meditation.” At this level of meditation, there is no longer any way to distinguish between the meditative session and the subsequent state of consciousness. In other words, there is no difference between the state of realization when one is engaged in meditation and the state of consciousness when one leaves the state of meditation. At this point the practice has become complete. There is nothing more to learn. This is the state of perfect enlightenment, or Buddhahood.

To use a worldly example, you could say that this path of meditation is like learning to drive a car. In the beginning it takes a lot of effort, there is a lot of doubt and hesitation. You constantly need to think of all the different things to do, and trying to do them all at the same time requires great effort and a lot of concentration. There are various dangers and many mistakes one can make. Gradually one becomes more and more accustomed to it, and so it requires less effort and is more natural. Finally, in the end when one gains complete mastery over the process of driving a car, one gets into the car and arrives at one’s destination almost without thinking about driving. One’s mind is thinking about other things because driving a car has become completely natural. Meditation is like that. When one attains this final level of meditation, it’s really like not meditating at all, therefore it is called non-meditation. Even though it is a profound state of meditation, there is no entering the meditative state or leaving it. One’s mind constantly abides in that perfect and complete knowledge.

These four levels can be correlated with the former three categories of the greater, middle, and lesser practitioners. Each of them applies to these four stages of practice. We can distinguish one’s progress on this path of Mahamudra with many variations and levels. The stages of this path were outlined by Phagmo Drupa in accordance with the teachings of Dharma Lord Gampopa. He combined Gampopa’s teachings on these four levels of yogic attainment with the three levels of practitioners, making twelve different levels of practice.

(1) The first level of yogic attainment was called the “one pointed yoga,” where mind becomes stabilized on its object. That is, it can hold an object one-pointedly without distraction, without losing it for a certain amount of time. So, one pointed meditative concentration can exist at various levels; it can be held more or less firmly for different lengths of time. If we look at this from the point of view of the practitioners:

– The lesser practitioner is able to hold clear concentration at times and loses it sometimes.

– The middle-level practitioner is able to maintain stable concentration so long as effort is being exerted. In other words, as long as that individual wishes to hold an object one-pointedly in mind, that object will remain in focus without distraction. Even between sessions when the individual practitioner is not trying to do it, sometimes that object will arise spontaneously and can be held one-pointedly But it will always appear one-pointedly when the practitioner so desires.

LOW LEVEL OF PRACTITIONER

|

One-pointed Yoga. |

Sporadic concentration. |

|

Yoga free from projection. |

Limited view of reality. |

|

Yoga of one taste. |

Unity of all phenomena. |

|

Yoga of meditation and non meditation. |

Unbroken flow of realization. |

MIDDLE LEVEL OF PRACTITIONER

|

One-pointed Yoga. |

Consistent concentration with effort. |

|

Yoga free from projection. |

Penetration to the root of reality. |

|

Yoga of one taste. |

Fullness of non-duality. |

|

Yoga of meditation and non meditation. |

Effortless manifestation of the three bodies. |

HIGHEST LEVEL OF PRACTITIONER

|

One-pointed Yoga. |

Continuous, effortless concentration. |

|

Yoga free from projection. |

Completely free of all delusion about phenomena. |

|

Yoga of one taste. |

Subtle apprehension of non-duality. |

|

Yoga of meditation and non meditation. |

Perfect, complete enlightenment. |

– The highest level of practitioner is able to hold that one pointed focus at all times, not just during a meditative session, but between sessions as well. Even in sleep, focus remains on that object effortlessly At that point, there may arise in the mind of such a practitioner the mistaken thought that the fourth, the highest, level of practice has been attained.

However, this is not true. What has actually been attained is the ability to hold the object one-pointedly without effort, and this is not the same as the state of non-meditation.

There are other factors which define this highest level of the initial stage. This practitioner has completely turned away from worldly involvement; his sense of renunciation of the world is complete. The practitioner has lost all interest in worldly pleasures. Even the desirable aspects of the world no longer hold any attraction. Therefore, he naturally stays in an isolated place conducive to meditation without any effort or sense of being deprived. He enjoys and feels very natural in that state of meditative isolation. In addition, there is a sense of complete devotion to the spiritual teacher in this state. The mind is never directed elsewhere, but rather remains completely directed toward the spiritual teacher, toward acquiring the teachings, and toward practising them. Beyond that, there is no interest or desire.

(2) The second level of yogic attainment is the stage of being free from projections. This is the stage where the nature of mind has been directly cognized. That is to say, ultimate reality has been seen face to face, directly experienced in a non-conceptual manner and, because of this, it is said to be free of projections. Projections are all of the conceptual elaborations used to explain or relate to the world. Having seen reality in its essence, there is no need for them. This stage also has levels that correspond to the three levels of practitioners:

A – Upon first directly cognizing the nature of mind, the lowest level of practitioner still has a limited view of reality. Although reality has been cognized and seen directly the fullness of it has not been experienced. There are still many aspects of phenomena which have not been understood, and many aspects of the path which are still unclear. So there is some hesitation and doubt in the mental processes of such a person. The basic nature of reality of mind has been experienced, but this has not yet been extended so as to clear away all doubts and illusions. What is necessary at this point is full and diligent engagement in yogic practices under the direction of a qualified spiritual teacher. This will allow that initial experience of reality to expand and clear away all doubts and all illusions.

B – The second level of practitioner at this second stage of yogic attainment has not only seen reality face to face, but has penetrated to its very root and, in doing so, has cut off the root of delusion. At this point, with this direct realization of the nature of mind in all of its profundity, the individual becomes totally free of all fears and gains complete control over his or her mind. Having gained total control over mind, over reality itself, it is irrelevant to this practitioner whether he goes to the deepest pit of hell or ascends to the highest heaven. All reality has one taste, so there is this experience of complete freedom and unobstructedness. The danger here is that the practitioner again thinks that he has arrived at the final goal when, in fact, there is much still left to do a long the path. This state is compared to the time in the morning when the sun is just rising above the horizon and illuminates the whole world, dispelling all the darkness and shadows. There is a sense that all of the darkness has gone away. However, the rays of the sun have not yet warmed things like the rocks and the trees. Various things are still cold from the night air, yet to be warmed by the rays of the sun. Likewise, for the middle-level practitioners at this second stage of yogic realization, the understanding of reality has not penetrated the entire extent of their mental processes. They still have doubt and uncertainty about various things; there are still remnants of hesitation about the nature of reality especially about the implications of the realization which has been experienced.

At first it seems to be a complete realization, but there gradually dawn various sorts of doubts. Questions arise. What has created this problem here or that problem there? At this stage of initial mastery one should rely on the scriptures, the sacred writings of the words of the Buddha and the great masters, in the direction of a fully qualified spiritual teacher. In order to extend the direct realization of reality and understand all of its implications, a further accumulation of merit is required through such things as offering mandalas, further study of the sacred texts, and especially cultivation of compassion for the suffering of living beings. In a sense, this remains a mystery to a person at this stage: when the nature of mind is beginningless and endless, non-abiding and completely pure, free and unobstructed, how can living beings experience misery in this way? How can that be relieved? So, this is a process of renewing one’s cultivation of loving-kindness and concern for the welfare of all living beings.

C – The highest practitioner who reaches this second stage of yogic realization becomes completely free of all delusions about inner and outer phenomena. In other words, this is a complete realization of the ultimate nature of all phenomena which is beyond the dichotomy of subject and object and all the elaborations of projections which are based upon that dualistic thinking. This is a powerful realization of non-duality which frees the practitioner from the illusions of the phenomenal world and from the sense of separateness from all phenomena. However, the danger here is that this can appear to be the attainment of the dharmakaya. If the practitioner holds to it as such, this is an error. So, what is needed is reliance on the words of a spiritual teacher, thereby understanding the profound and subtle nature of the ultimate level of realization and the fact that there is more work to be done to completely fill out this realization and internalize it.

There is a tendency within this category of yogic attainment, especially in those who first reach it, to feel that they have made a mistake or lost their way on the path. This is because during the initial stage of yogic attainment there is the perfect, effortless, one-pointed concentration on the object of meditation.

Upon arrival at the second stage of yogic realization, there is an opening up. In contrast to the narrow focus on an object, there is an opening up of consciousness in the direct realization of the nature of mind. This can be interpreted as a loss of one-pointed concentration. That error must be transcended. One must understand that one-pointed concentration was a device, or an artifice, to allow mind to get beyond the distractions which prevent direct insight into mind. So, arriving at this second yogic state and reaching the level of the highest practitioner, there is complete freedom from all projected activity of mind, and mind becomes stabilized on reality. At this point there are still other qualities to be developed, specifically those associated with loving- kindness and compassion and the bodhisattva attitude. So, this is what arises at this point, the bodhisattva attitude which seeks to attain perfect enlightenment in order to help all living beings transcend the misery of samsara. This feeling is no longer artificial, but rather it begins to arise spontaneously from this pure view of reality this freedom from all projection. Realizing the misery of all living beings, great compassion arises spontaneously. At that point, one enters into a deeper and more profound practice which seeks to gain all the necessary attributes and powers to actually alleviate the miniseries of limitless sentient beings. At this highest level of practice of the second stage of realization, there is a sense that one has gone beyond the need for meditation or learning. If this were true, the practitioner would actually be at the highest stage of yogic realization, but this state of independence has not been reached yet. If the practitioner feels that the work of one-pointed concentration has been completed, that the freedom from projections is complete, that the loving concern for others has been developed, and nothing remains to be done, this is incorrect. There are still certain types of development which must take place.

Lord Gampopa taught this to his disciples, and it was written down by Nampopa, one of those disciples. He said that the type of pride which arises at this stage, thinking that the path has been completed and that there is nothing more to learn or to meditate on is an error. What has been attained is a complete freedom from the delusions associated with ordinary ignorance, but the delusions associated with cause and effect have not been eliminated.

The ordinary delusions are those that have to do with the perceptible world, what is directly perceived. Those which have to do with karma are things that cannot be directly perceived. So, the distinction here is that the obstacles to the state of perfection extend to ultimate things. In other words, there is full realization of ultimate reality by the highest level of practitioner at this stage of yogic practice. However, conventional reality has not been completely understood. What has been realized is the way things actually are, but not the way things appear. What is left to be done is to understand directly the way things appear and to unite that with the realization of the way things actually are. In other words, the conventional and ultimate must be joined together and not be seen as distinct.

(3) The next stage of yogic realization is called “the level of one taste.”

For the lowest level of practitioner, there is one taste between subject and object. Mind and its objects, inner and outer, are realized in their unity. In the former state there was still a lack of integration of the realization of the conventional and the ultimate, the way things appear and the way things actually are. At this level, one has solved that problem, and everything has one taste. Samsara and nirvana are seen as one.

As the great protector of living beings Nagarjuna said, “The complete understanding of samsara is nirvana. To completely realize the nature of samsara is to attain nirvana.” Making a dichotomy between samsara and nirvana is ultimately a mistake. They are not of different natures. At this point, the practitioner attains the state of non-duality the complete realization of non-duality. He realizes that there is no one wandering in samsara. There is no being wandering in samsara, nor is there a being who attains enlightenment or attains Buddhahood. These are false dichotomies.

All phenomena of samsara and nirvana have one taste, one reality. Through the force of this powerful realization, the practitioner can again make the mistake that he has reached the ultimate stage of no more learning where no more effort or meditation is necessary.

The middle-level practitioner has cut the root of all dualistic thinking. Realizing non-duality in its fullness, he sees all of reality inner and outer, subject and object, as one. He has a sense of full enlightenment wherein nothing whatsoever, no subject or object, is separate from this directly perceived unity This experience of vast oneness is so powerful that there is a danger of accepting this as full enlightenment and neglecting the miseries of living beings. Living beings, hen, are not categorized as those who suffer the miseries of cyclic existence and those who enjoy the ultimate bliss of full enlightenment. They are all part of this completely integrated whole, or oneness, into which one has become fully integrated. That is the danger here, to lose the sense of compassionate concern for the sufferings of living beings or to experience them as part of this wondrous, non-dual reality.

For the middle-level practitioner at this stage of one taste, the realization of oneness (non-duality) can lead to a loss of contact with, or loss of understanding of, the miseries of others and a consequent separation from the basic work of bringing about the welfare of all living beings. This is a great fault that must be corrected at this stage. Again, the correction comes through full and devoted reliance on a qualified teacher who is able to point out methods to appreciate the reality of the misery of living beings. Up to this stage, the practitioner has been encouraged to perfect the meditation in isolation from the world. Now the practitioner is encouraged to re-enter the world by going to the town or marketplace to view directly living beings in all of their activities, difficulties, and ignorance. In this way he will regain an appreciation of the nature of cyclic existence and the pressing need for someone to engage in the activities which bring about the welfare and liberation of these living beings.

The highest level of practitioner at this yogic stage of realization of one taste also realizes complete non-duality, but he does so in a more subtle way. All phenomena of samsara and nirvana are appreciated in their own aspects, even though the essence of the reality is one. Here also there is the possibility of falling into a state which is neglectful of the needs of living beings because complete oneness and non-duality are experienced. However, the realization is more subtle, so the antidote (i.e., the practice to be engaged in at this point) is somewhat different.

The medium-level practitioner needed to go into the world and perceive the misery of living beings, and thereby cultivate what is called “the compassion which apprehends living beings.” Now, at this higher level, what is cultivated is compassion which is not directed toward any object. This is sometimes called “limitless compassion” because it does not focus on living beings as such, but rather is a compassion that radiates out in all directions and accomplishes the welfare of living beings according to their individual needs and dispositions. That universal compassion, developed under the guidance of a qualified spiritual teacher, is not limited to any number of living beings but is spontaneous and constant in its nature.

(4) Next is the highest of the four stages of yogic realization. This is the non-meditative stage where all effort in learning has been accomplished. It is called “non-meditative” because meditation is no longer separate from anything else. It is a state in which the meditation practice and non-meditation (or time between sessions of meditation) cannot be distinguished. Mind abides in this state at all times, so there is no longer any sense to labelling it meditation or not meditation.

Here, the lowest level of practitioner has achieved a stage which is said to be free of realization. What this means is that the meditation proceeds in an unbroken flow like a river which continues without a break. There is no sense of discovery or realization; no conception of realizing an object or arriving at a realization that something arises. It is just an unbroken stream of perfect, non-dual awareness. So it is said to be free of meditation, free of realization, but unbroken as a stream of pure enlightenment. The middle level of practice at this highest stage of realization is such that the three bodies are manifested without exertion: the one body which is the perfection of one’s own welfare (the Dharmakaya) and the two bodies of the enlightened one which perfect the welfare of others (the Nirmanakaya and Sambhogakaya). These arise naturally through the unbroken stream of enlightenment which is free of the effort of meditation and of the interruption of discrete realizations.

Last is the highest level of practice at this highest stage of yogic realization. All good qualities have been attained, so compassion for living beings arises spontaneously and uninterruptedly as do the activities which benefit living beings.

Compassion is perfectly without objectification. It does not take up the cause of one being or another, but rather radiates out in all directions and manifests constantly according to the needs and requirements of all living beings. The realization at this stage is without any limit, without any obstructions in terms of the subject or object. The realization is complete and total. There is no longer any dependence upon causes or conditions. All the causes and conditions of total, perfect, peerless enlightenment have been met and, so, the ultimate goal is obtained.

So here we have discussed the twelve stages in the development of Mahamudra practice, from the beginning stages of realization to the attainment of the ultimate goal of perfection. This brief explanation was presented according to the tradition of Dharma Lord Gampopa.